Strike Leaders

Hold on boys, here’s Ivens coming,

Russell, Winning too,

Take this answer to our masters:

We are staunch and true

– Singing by a crowd of strikers on June 10, 1919, as reported in Western Labor News.

Strike Committee

The Strike Committee was the primary governing body of the General Strike. However, the official Strike Committee was not established until May 21, seven days into the strike, and was therefore not itself responsible for organizing the strike in the first place. Rather, it was the Winnipeg Trades and Labor Council (WTLC) that called and organized the strike.

The WTLC was an organization comprised of 95 unions across Winnipeg, representing about 12,000 individual men and women. Its function was to advocate on behalf of its member unions, either individually or as a whole, and to coordinate the efforts of these unions to increase the effectiveness of collective bargaining. How this was to be accomplished was the source of some division within the WTLC. Traditionalists advocated for a labour party and craft unionism (the division of unions by job and skill-set) while those of a more socialist persuasion advocated for direct action and industrial unionism (a single union representing an entire industry, regardless of job or skill-set).

Nonetheless, the WTLC acted as a united front when Building and Metal Trades workers went out on strike in 1919, on May 1 and May 2 respectively. The WTLC organized a vote on whether to call a General Strike in support of two trades councils. Once the vote results came back in favour, the WTLC sent word to all affiliated unions that the General Strike would take place on May 15 at 11 am.

To coordinate and govern the strike, the WTLC set up an interim committee until a more formal apparatus could be implemented. This committee consisted of R.B. Russell, John Queen, James Winning, H. Veitch, and J.L. McBride (Masters 1973, 45). On May 21, the Strike Committee was established, consisting of three members from each of the 95 unions and five members of the WTLC, which added up to 290 members in total (though it was often reported as 300). The Strike Committee proposed and voted on policy decisions and generally directed the strike. To support such a large committee, a bureaucracy was created that included positions such as Chairman and Secretary. As well, a smaller executive was created, consisting of 15 members to deal with matters of great importance that required expedience.

Historian D.C. Masters differentiates between a “General Strike Committee”, the 290-member committee, and a “Central Strike Committee”, the executive (Masters 1973, 46), but the Western Labor News often used the latter term to refer to the 290-member committee as well (see, for example, Western Labor News, May 19, 1919). The executive reported directly to the Strike Committee and its membership consisted of all those on the interim committee (excluding John Queen), as well as labour leaders such as E. Robinson and W.H. Lovatt. These men were all established names in the labour movement, were all of British descent, and were mostly moderate craft unionists, with the exception of R.B. Russell, a socialist and industrial unionist who was one of the most influential leaders of the strike.

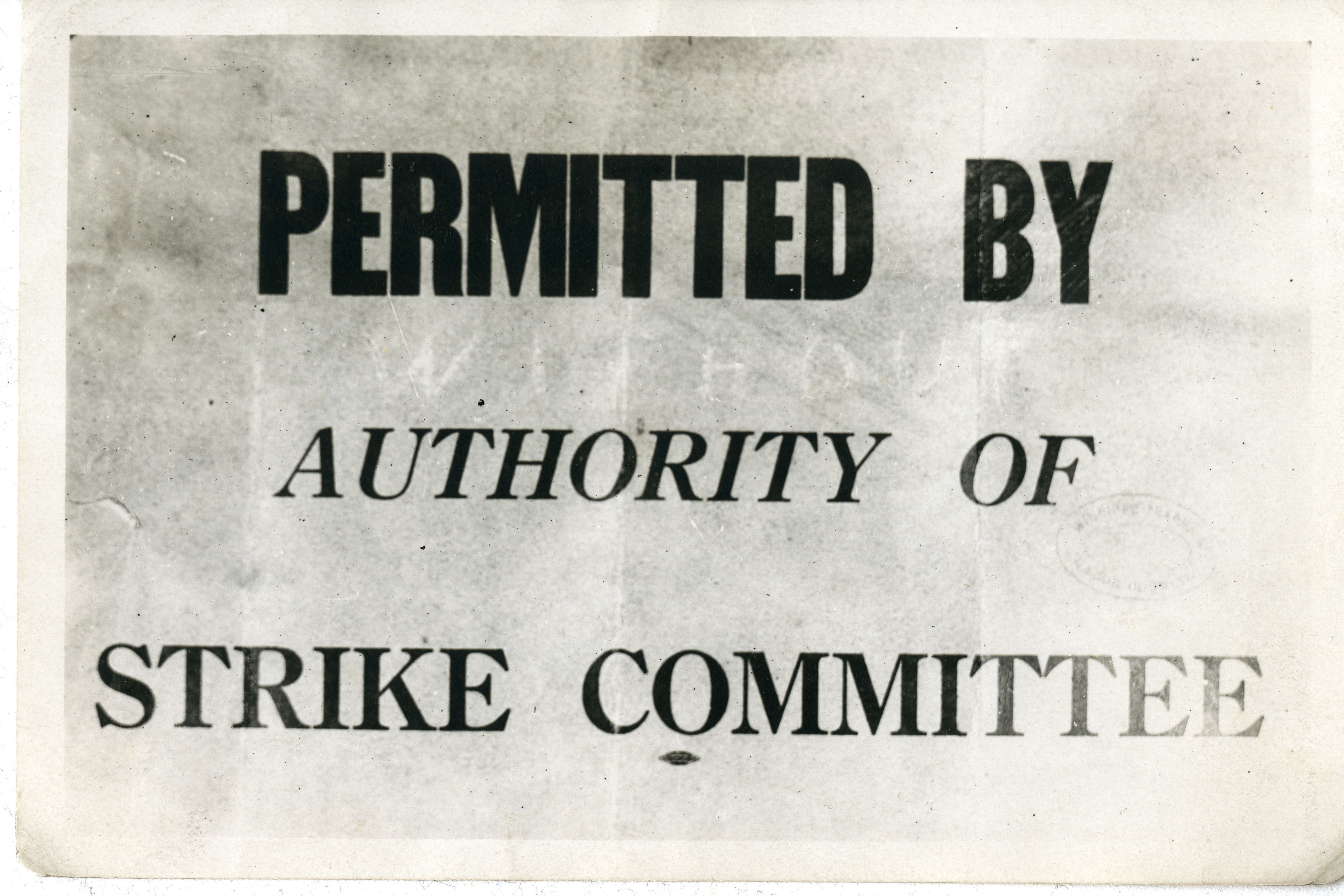

During the strike, the day to day operations were carried out by various sub-committees that served specific functions, such as managing finances, press, relief, and food, as well as a commissariat that supported the strikers’ efforts. The Strike Committee decided which workers left their posts and which remained. It also issued authorization documentation to certain businesses and services it felt were necessary to continue to operate, so long as it was known that it was at the Strike Committee’s behest. Information about these operations, as well as updates on the negotiations the Strike Committee was engaged in, were communicated through the Western Labor News’ daily Strike Bulletin, and through daily gatherings in Victoria Park.

On June 17 several of the strike’s most influential leaders were arrested and charged with seditious conspiracy. Of these, R.B. Russell was the only member of the Strike Committee’s executive. On June 25, the Strike Committee called off the strike and it officially ended the following day. Though the Strike Committee had no more reason to exist, a new committee, the Defence Committee, took its place. This committee raised funds for the legal expenses of the strike leaders who were on trial, raised funds for their families, and began a nationwide awareness campaign, which included the accused touring the country while on bail and the publishing of pamphlets and literature. After the trials had ended and several of the strike leaders were convicted, the Defence Committee unsuccessfully attempted to appeal their verdicts and continued to provide money to the families of those imprisoned.

Strike Committee Executive

Mr. Allen • G. Anderson • Thomas Flye • W.H.C. Logan • W.H. Lovatt • J.L. McBride • W. Miller • Mr. Noble • Laurence Pickup • E. Robinson • R.B. Russell • N. Shaw • Mr. Smith • H.G. Veitch • James Winning

Trades Councils

The Building Trades Council (BTC) was formed in 1903 as a way for various building trades unions to collaborate and support one another. In Winnipeg, the building industry was booming, which almost guaranteed skilled building trades workers were in high demand. Building trade workers had a relatively good relationship with their employers in the Builders’ Exchange, which represented contractors, suppliers, and other employers in the building industry. Though the two often attempted to outflank each other in negotiations, the Exchange generally recognized the negotiating power of the BTC and employees rarely made public attacks on their employers (Bercuson 1990, 27-28). However, this began to change in 1913, when a depression set in, and worsened in 1914, after the outbreak of the First World War. As all necessary funds were being diverted to the war effort, the rate of building dropped considerably. Many of the BTC’s members were out of work, forcing it to subsidise their union dues. As employment dropped, so did membership. The Builders’ Exchange was also affected by the drop in construction and sought to mitigate their losses by undercutting and underpaying their employees. Employment improved by 1916, but it left a lasting tension between employees and employers (Bercuson 1990, 27).

The Building Trades Council (BTC) was formed in 1903 as a way for various building trades unions to collaborate and support one another. In Winnipeg, the building industry was booming, which almost guaranteed skilled building trades workers were in high demand. Building trade workers had a relatively good relationship with their employers in the Builders’ Exchange, which represented contractors, suppliers, and other employers in the building industry. Though the two often attempted to outflank each other in negotiations, the Exchange generally recognized the negotiating power of the BTC and employees rarely made public attacks on their employers (Bercuson 1990, 27-28). However, this began to change in 1913, when a depression set in, and worsened in 1914, after the outbreak of the First World War. As all necessary funds were being diverted to the war effort, the rate of building dropped considerably. Many of the BTC’s members were out of work, forcing it to subsidise their union dues. As employment dropped, so did membership. The Builders’ Exchange was also affected by the drop in construction and sought to mitigate their losses by undercutting and underpaying their employees. Employment improved by 1916, but it left a lasting tension between employees and employers (Bercuson 1990, 27).

These tensions ramped up in April 1919, when the BTC began to negotiate contracts with the Builders’ Exchange directly, rather than via the Manitoba Fair Wage Board. While this new arrangement was initially welcomed by the Exchange, as being able to make a single, industry-wide deal appealed to it, both sides had different ideas about what was a fair increase in wages. The cost of living had skyrocketed in post-war Winnipeg, and the BTC wanted a wage to reflect this. On April 24, they demanded a 20 cent per hour increase for all employees across the board. This amounted to an increase of up to 50 percent for some employees. The Exchange acknowledged that anything less than what was being asked for would not constitute a living wage, but claimed they could not do business with such an increase. In a counter offer made April 28, they offered a 10 cent increase for some workers and as low as 5 cents for others. Furthermore, if the deal was not accepted, the Exchange threatened to undermine the BTC by refusing to recognize its authority and would only negotiate with individual trade unions. This was unacceptable to the BTC and on April 30, they took a strike vote. The decision was not an easy one. As the BTC was now an industrial union that was not sanctioned by the international union, its members would not receive strike pay (Bercuson 1990, 112). Nonetheless, on May 1, they walked off the job.

After the General Strike began on May 15, partly in sympathy with the BTC, negotiations began between the BTC and the Strike Committee (primarily represented by James Winning), their employers, the Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand, and the City of Winnipeg. However, these negotiations went nowhere, as the Citizens’ Committee had convinced the Builders’ Exchange that nothing other than unconditional surrender should be accepted. This ground negotiations to a halt. Even after the strike ended on June 26, it wasn’t until June 30 that the BTC and the Exchange finally reached a settlement. Despite the Exchange’s earlier rhetoric, the employees received wages in excess of that which the Exchange had offered prior to the strike – as high as 15 cents per hour. But these increases were the result of negotiations between the Exchange and individual trade unions, not the BTC as a whole.

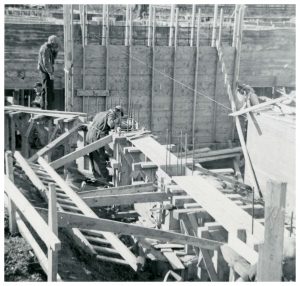

Image Source: Builders, 1946. COWA. Photograph Collection (P28 File 1)

The Metal Trades Council (MTC) was formed in April 1918, when railway shop unions began a campaign to organize all metal trades into a single, industry-wide union. The MTC was comprised of six different unions with J.R. Adair as its President and future General Strike leader R.B. Russell as its Secretary. It immediately began a campaign for recognition by employers. In June, it demanded higher wages and better conditions from 45 shops across Winnipeg, threatening a strike on June 10 if their demands weren’t met. The proposed wages were far higher than what was provided elsewhere in Canada, but the true purpose of the demands were to gain recognition by employers (Bercuson 1990, 72). The iron masters (a term used collectively for Winnipeg’s metal works employers, especially those of the three big shops, Vulcan Iron Works, Manitoba Bridge and Iron, and Dominion Bridge Co.) refused to even negotiate with the MTC. Several attempts at negotiation failed and on June 26, Justice T.G. Mathers was appointed to lead a royal commission to investigate the dispute. Mathers was joined by Winnipeg Alderman George Fisher and Winnipeg Trades and Labor Council (WTLC) president F.G. Tipping. R.B. Russell represented the MTC. The two sides became deadlocked and Russell called an industry-wide strike on July 22. Furthermore the WTLC threatened to hold a general strike vote if a settlement wasn’t reached (Bercuson 1990, 74). Mathers’ report was submitted on August 2 and listed recognition of the MTC as the most significant dispute between the two sides, but also heavily critiqued the actions of the MTC. Though the MTC strike fizzled out soon after, Tipping’s signature on the report lost him his position as WTLC President.

The Metal Trades Council (MTC) was formed in April 1918, when railway shop unions began a campaign to organize all metal trades into a single, industry-wide union. The MTC was comprised of six different unions with J.R. Adair as its President and future General Strike leader R.B. Russell as its Secretary. It immediately began a campaign for recognition by employers. In June, it demanded higher wages and better conditions from 45 shops across Winnipeg, threatening a strike on June 10 if their demands weren’t met. The proposed wages were far higher than what was provided elsewhere in Canada, but the true purpose of the demands were to gain recognition by employers (Bercuson 1990, 72). The iron masters (a term used collectively for Winnipeg’s metal works employers, especially those of the three big shops, Vulcan Iron Works, Manitoba Bridge and Iron, and Dominion Bridge Co.) refused to even negotiate with the MTC. Several attempts at negotiation failed and on June 26, Justice T.G. Mathers was appointed to lead a royal commission to investigate the dispute. Mathers was joined by Winnipeg Alderman George Fisher and Winnipeg Trades and Labor Council (WTLC) president F.G. Tipping. R.B. Russell represented the MTC. The two sides became deadlocked and Russell called an industry-wide strike on July 22. Furthermore the WTLC threatened to hold a general strike vote if a settlement wasn’t reached (Bercuson 1990, 74). Mathers’ report was submitted on August 2 and listed recognition of the MTC as the most significant dispute between the two sides, but also heavily critiqued the actions of the MTC. Though the MTC strike fizzled out soon after, Tipping’s signature on the report lost him his position as WTLC President.

While the MTC continued to fight for better wages, better conditions, and recognition, the iron masters continued to refuse to negotiate with it. In spring 1919, new demands for better wages and conditions were sent to various employers, but only three responded. On April 30, the MTC voted to strike if one final attempt to negotiate failed. Workers walked off the job on May 2. As the strike unfolded, the interests of the MTC were represented by the Strike Committee as a whole, and R.B. Russell, who was present at most settlement negotiations, up until his arrest on June 17. These negotiations were usually facilitated by Mayor Charles Gray and City Council. The iron masters were initially open to negotiations, but they were even more open to the Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand, which convinced them to shut down all negotiations until the men were back at work. The best the iron masters offered was on June 16, when they offered to recognize individual trade unions. Recognition of the MTC was never on the table. When the General Strike ended on June 26, the MTC continued to fight for a few more weeks, but workers continued to trickle back to work and by early July, their resistance had run out of steam. Workers were given a slightly reduced work week – 50 hours as opposed to 55 – at the same pay, but the MTC was never recognized.

Image source: Metal workers at Dominion Bridge Co., 1940. COWA. Photograph Collection (P9 File 33).

Strike Leaders

George Armstrong was born in Ontario in 1870. Prior to coming to Winnipeg, Armstrong spent a few years in the United States, during which time he was involved in a labour dispute in Buffalo, New York. In 1905, Armstrong came to Winnipeg with his wife, Helen (née Jury). Armstrong was actively involved in the labour movement in Winnipeg; a carpenter by trade, he helped organize the Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners of America and was a member of the Socialist Party of Canada. In 1910, Armstrong threw his hat into the ring for a seat in the Manitoba Legislature, running as a Socialist for Winnipeg West. He ran unsuccessfully and tried again in Winnipeg Centre in 1914, losing the latter race to Fred Dixon, whom would later be a fellow leader of the General Strike.

George Armstrong was born in Ontario in 1870. Prior to coming to Winnipeg, Armstrong spent a few years in the United States, during which time he was involved in a labour dispute in Buffalo, New York. In 1905, Armstrong came to Winnipeg with his wife, Helen (née Jury). Armstrong was actively involved in the labour movement in Winnipeg; a carpenter by trade, he helped organize the Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners of America and was a member of the Socialist Party of Canada. In 1910, Armstrong threw his hat into the ring for a seat in the Manitoba Legislature, running as a Socialist for Winnipeg West. He ran unsuccessfully and tried again in Winnipeg Centre in 1914, losing the latter race to Fred Dixon, whom would later be a fellow leader of the General Strike.Armstrong served his sentence at Stony Mountain Penitentiary and the Birch River Prison Farm. Due to his experience as a carpenter, Armstrong was appointed head carpenter and helped to build the hen coops. Helen often visited the prison and provided moral support. Sometimes she brought choirs to sing outside of the penitentiary to entertain her husband and fellow inmates.

In 1920, while still serving his sentence, Armstrong was elected the first, and – to this day – the only socialist member of the Manitoba Legislature. On February 28, 1921, Armstrong was released from prison and was sworn into office that same day. He lost the seat two years later and was never able to regain it. As well, his involvement in the strike made it difficult for him to find work outside of politics. As a result, Armstrong and his family moved to Chicago in 1924, but were forced to return due to the start of the Great Depression. Armstrong moved to Victoria in 1945, where he retired. Shortly after, he and Helen moved to California, where he died in 1956.

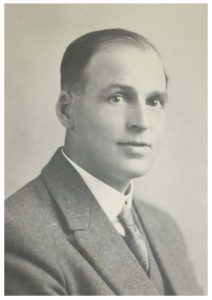

Image source: Winnipeg Tribune, March 27, 1920. UML.

Helen Jury Armstrong (née Jury) was born in Toronto in 1875, the eldest of 10 children. Growing up, Armstrong worked as a tailor in her father’s store and was exposed to labour ideals at a young age. Her father was actively involved with the Knights of Labor and often hosted gatherings of fellow members in his store. In the years that followed, she met George Armstrong, a carpenter who shared similar views, and the two were married in 1897. They moved to the United States for a few years and made their way back to Canada, where they settled in Winnipeg in 1905. Here, Armstrong quickly found her way to the James Street Labor Temple, where she worked with the Winnipeg Trades and Labor Council and became the leader of the Winnipeg branch of the Women’s Labor League. In this role, Helen was an advocate for women, campaigning for better wages and union organization for the female workforce. She was against conscription, an unpopular view in the midst of the First World War.

Helen Jury Armstrong (née Jury) was born in Toronto in 1875, the eldest of 10 children. Growing up, Armstrong worked as a tailor in her father’s store and was exposed to labour ideals at a young age. Her father was actively involved with the Knights of Labor and often hosted gatherings of fellow members in his store. In the years that followed, she met George Armstrong, a carpenter who shared similar views, and the two were married in 1897. They moved to the United States for a few years and made their way back to Canada, where they settled in Winnipeg in 1905. Here, Armstrong quickly found her way to the James Street Labor Temple, where she worked with the Winnipeg Trades and Labor Council and became the leader of the Winnipeg branch of the Women’s Labor League. In this role, Helen was an advocate for women, campaigning for better wages and union organization for the female workforce. She was against conscription, an unpopular view in the midst of the First World War.

On March 13, 1919, Helen was a delegate at the Western Labor Conference in Calgary, along with her husband. As a delegate, Helen supported the One Big Union, which was used against her by anti-strike media during the General Strike. They often reminded their readers that the Helen Armstrong their articles were referring to was that Helen Armstrong who had attended the convention in Calgary.

When the strike began in 1919, Armstrong led women and their families through many struggles. As head of the Women’s Labor League, she organized a kitchen at the Strathcona Hotel and, later, the Oxford Hotel, where women who struggled to feed themselves and their families due to the strike could get free meals. She campaigned for and organized walk-outs of women who worked as retail clerks, telephone operators, laundresses, and others. She often approached female employees at their place of work and attempted to convince them to join the strike. She further encouraged women to target those who continued to work, which landed herself in jail on more than one occasion. She was so successful, that she became a target of anti-strike newspapers. The Winnipeg Citizen stated on more than one occasion that Armstrong had herself admitted to being committed to an asylum, a story they never corroborated with any sources.

In the aftermath of the strike, the Armstrong family struggled. Helen’s husband George was convicted of seditious conspiracy in March 1920. She would visit Stony Mountain frequently to see her husband until his release the following year, and sometimes even organized a choir of children to accompany her and sing outside of the prison to entertain her husband and other inmates. In 1923, Helen ran an unsuccessful campaign for Winnipeg City Council and, due to the reputation her and her husband had gained during the strike, stable employment did not come easily. Consequently, she and her husband moved to Chicago to seek out better employment opportunities, but were forced to return when the Great Depression made jobs scarce there as well. In 1945, Armstrong and her husband moved to Victoria and then to California, where she died on April 18, 1947. She is buried in Los Angeles.

Image Source: Winnipeg Tribune, November 9, 1923. UML.

For more information on Helen Armstrong’s involvement in the strike, see Who: Women

Not much is known about Samuel Blumenberg’s life before the strike. He was born in Romania, possibly in or around 1884. He emigrated to the United States as a child, and was orphaned at a young age, though it is not clear if either or both of his parents were still alive at the time of his emigration. He settled in Minneapolis, where it is believed he later met and married Ms. Silver (various records refer to her as Annie or Libby). He moved to Winnipeg where he worked as a tailor. He paid homage to his time in the United States by establishing the Minneapolis Dye House at 470 ½ Portage Avenue.

Blumenberg was an ardent socialist, which gave him a reputation as being a fanatic. He opposed the First World War and conscription, had named one of his children after Karl Marx, and believed that socialism would overtake Winnipeg and the country. He spoke publicly about these views and further wrote plays about them, such as “War – What For?”, a play written in honour of the victims of the Lusitania which was described as “One of the most Radical plays ever produced on any stage” (The Voice, June 11, 1915). As president of the Winnipeg chapter of the Socialist Party of Canada, Blumenberg was an obvious target for those who placed themselves firmly against Socialism and leftist-politics. While attending the Walker Theatre meeting in December 1918, he was flagged by an undercover agent as wearing a red tie – a choice that was interpreted as a blatant flaunting of his socialist sympathies. His ethnic origins also made him a target, such as in January 1919 when, over the span of two days, a mob made up of civilians and returned soldiers targeted businesses owned by so-called enemy aliens and those who employed or sympathized with them. As a Jew from Eastern Europe, Blumenberg’s dye works business was targeted and vandalized. The mob broke his windows and machinery. The mob sought out Blumenberg himself, but he managed to evade them, so the mob instead dragged out his wife and made her kiss the flag. Following the event, Blumenberg headed to Minneapolis to lay low. He returned to Winnipeg in the spring.

A warrant for Blumenberg’s arrest was issued on June 17, 1919. Blumenberg turned himself in that same evening and was charged with seditious conspiracy. As he was not born in Canada, he faced deportation under the Immigration Act, which had been recently amended specifically to target leaders of the General Strike. Blumenberg was put in an awkward position during his deportation hearing as he was required to answer questions that could be used as evidence against him in court if it was decided to prosecute him criminally. Following an investigation by the Special Board of Inquiry of the Immigration Board, an order for Blumenberg’s deportation was made in August of 1919. Blumenberg was scheduled to be deported back to Romania but left for the United States before his deportation date. He settled back in the Minneapolis area, where he continued to work as a labour organizer and ran as a socialist candidate in a municipal election. He later moved to California where he became a business agent for the International Association of Cleaning and Dye House Workers until he was ousted in the late 1930s, following a reorganization. In 1939, following what was described as launching “a terrorism campaign against independent cleaners and dyers who refused to raise prices”, Blumenberg, along with eight other men, was convicted of plotting terrorism through “stench bombings and acid assaults” on stores that rejected attempts by cleaner associations to fix prices at higher rates (Los Angeles Times, January 6 and February 16, 1939). Blumenberg was sent to San Quentin Prison in 1942, but was released early, the following year, for time served. Blumenberg died around 1945.

Image Source: Winnipeg Tribune, November 13, 1918. UML.

For more information on the deportation trials of “enemy aliens”, including Blumenberg, see Who: Racialized Communities

Born in 1875 in Sheffield, England, Bray came to Winnipeg in 1903. Prior to the General Strike, Bray worked as a butcher and enlisted in 1916 to fight in the First World War, serving overseas until the end of 1918. As a veteran, Bray was well positioned to lead many of the returned soldiers who supported the Strike when it began in May 1919. His role as Chairman of the Returned Soldier Strikers made him a visible threat to those who opposed the strike and the authorities, including Constable W.H. McLaughlin, a police spy who referred to Bray as Winnipeg’s most dangerous man and claimed that Bray was planning a military takeover.

Bray was arrested alongside other Strike leaders on June 17, 1919. Following Bray’s arrest, J. Farnell led the pro-strike returned soldier. While awaiting trial, Bray was appointed Vice-chairman of Winnipeg’s One Big Union. When released on bail, he further toured Eastern Canada, heading to Toronto, Hamilton, Kitchener and Montreal alongside William Ivens in an effort to raise money for the strike defense fund, created to support strikers who were arrested.

Bray was represented in court by Robert Bonnar, who felt as though a fair trial could not be had in Winnipeg, particularly as four of the lawyers for the Crown were members of the Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand. Bonnar expressed a desire to withdraw from representing Bray, but continued for the duration of the trial. Six of the seven defendants at Bray’s trial were found guilty, including Bray, but unlike the others, Bray was only found guilty of creating a common nuisance, not of seditious conspiracy. He was, however, found in contempt of court by Judge Metcalfe following a statement in which Bray described the trial as a “travesty on British Justice” (Winnipeg Tribune, April 4, 1920). Bray served a six-month sentence on a prison farm where he worked as head poultryman.

At the time of his conviction, Bray had a wife and eight children, but lost his three-year-old son – who died playing with matches – while Bray was still serving his sentence. Of the convicted strike leaders, Bray was the first to be released on September 17, 1920, at 5 pm. Following his release from the Birch River prison farm, Bray arrived home in Saint Boniface via the Greater Winnipeg Water District railway and was greeted by his wife and daughter, Katie. In 1922, Bray ran unsuccessfully as an Alderman for Ward 3. Not much is known about Bray after these years. He continued to support the OBU and eventually moved to Vancouver where he grew and sold gladioli. He died on October 23, 1952 at the age of 77.

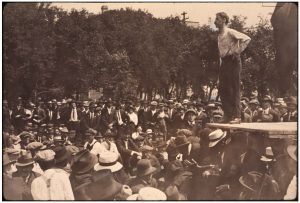

Image Source: Roger Bray speaking in Victoria Park during the Strike. WCPI A1293-38716, UWA.

For more information on Roger Bray’s involvement in the strike, see Who: Returned Soldiers

Dixon was born in Englefield, England on January 20, 1881. He apprenticed as a gardener before coming to Winnipeg in 1903, where he worked as an engraver and entered the realm of politics. Dixon ran an unsuccessful campaign in the Provincial election of 1910, but won a seat in the Legislature in 1914, running as an independent for Winnipeg Centre. With his seat in the Legislative Assembly, Dixon advocated for direct legislation, the nationalization of public utilities, an end to business subsidies, and the rights of workers and women. His wife, Winona Flett, was a suffragette and one of the founders of the Manitoba Political Equality League. Dixon also advocated pacifism and was against conscription; in 1917, he urged a crowd in Market Square to burn their conscription cards. During the scandal around Premier Rodmon Roblin and the construction of the new Legislature Building, Dixon pushed for a corruption investigation that culminated in Roblin’s resignation in 1915. Though Dixon was pro-labour, he was critical of socialism.

Dixon was also a writer who contributed to papers such as The Voice. He utilized this experience during the General Strike when he wrote for the Western Labor News, first as a reporter, following William Ivens’ June 17 arrest, and then as editor after J.S. Woodsworth was arrested on June 23, right in front of Dixon. When the Western Labor News was suppressed, Dixon began to publish under different titles, such as the Enlightener and the Western Star. He was finally arrested and charged with seditious libel on June 27, but was released on bail shortly afterwards.

His trial began on his 39th birthday – January 20, 1920. Though his friend Lewis St. George Stubbs had offered to defend him in court, Dixon wished to defend himself. He faced prosecutors Hugh Phillips, Joe Thorson, and Archie Campbell, who called nearly forty witnesses for Dixon to cross-examine. On February 14, Justice A.C. Galt dismissed the jury. Two days later, they acquitted Dixon of all charges. The case was groundbreaking, as Dixon had managed to convince the jury of his innocence simply through his address – having called no witnesses. Following the trial, Dixon continued to work in politics until poor health forced him to retire in 1923. Dixon died in 1931 following a battle with cancer.

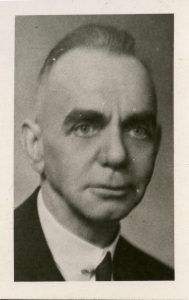

Image Source: Lewis St. George Stubbs fonds. UMASC.

Of Polish-Jewish descent, Abraham Albert Heaps was born in Leeds, England on December 24, 1885. He arrived in Winnipeg in 1911 and settled in the North End, where he worked as an upholsterer. Almost immediately, Heaps became involved in the labour movement, working as a statistician for the Winnipeg Trades and Labor Council. In 1917, he was elected to City Council, becoming an Alderman for Ward 5, which encompassed the southern part of the North End.

On the spectrum of labour politics, Heaps was a moderate. He did not support the One Big Union, but rather, believed in the idea of a labour party. He supported the pacifist, anti-conscription movement in 1917 and, in 1918, pushed City Council to take a conciliatory stance and to negotiate when civic employees went on strike.

When the General Strike broke out on May 15, 1919, Heaps played an active part as a leader of the strike, supervising the Commissariat of the Strike Committee, which provided supplies and entertainment to keep strikers busy and out of trouble. This put Heaps in an interesting position as being both a member of the establishment and a leader of the organization challenging it. After all, he was on many of the City committees that had to manage the sudden lack of staff. In Council, he generally voted in favour of the strikers, forming an inadvertent and unofficial pro-labour party with four other Aldermen. Council votes almost always ended in a nine to five result against Heaps’ unofficial caucus.

On June 17, Heaps was arrested alongside several other strike leaders and charged with seditious conspiracy and committing a common nuisance. Regarding the latter charge, Heaps stated that he did “not object to being called a nuisance…but being called common is carrying things too far” (Winnipeg Tribune Personality files). Heaps’ trial began in January 1920. His initial counsel having quit mid-trial, Heaps represented himself and critiqued the jury selection process, as it was heavily stacked against him and his co-defendants. Annoyed, Judge Metcalfe told the defendants that they were lucky it wasn’t like “olden times” when their guilt would have been determined by throwing them into a river to see whether or not they floated. To this, Heaps responded, “I think we’d stand more of a chance that way” (Larson 2015). Heaps successfully defended himself and was acquitted of all charges on March 27. As his co-defendants were all found guilty and were instructed by the Judge to stand, Heaps instinctively stood up with them until R.J. Johns reminded him, amused, “you are not a conspirator” (Winnipeg Tribune, 1920-03-29).

As an Alderman, Heaps continued to be popular with his constituents. He was re-elected to City Council, where he served until 1925, when he resigned to become a Member of Parliament for Winnipeg North. In 1927, with fellow strike leader turned MP, J.S. Woodsworth, Heaps introduced Old Age Pension, and on its founding in 1932, he joined Woodsworth and became a member of the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation (the precursor to the New Democratic Party). Heaps was finally defeated in 1940 and subsequently retired from politics.

Heaps died in 1954 while visiting relatives in Bournemouth, England, and was buried in his home town of Leeds.

Image Source: COWA. Art Collection (A01068)

For more information on A.A. Heaps’ involvement in the strike, see Who: Government & Politicians

Born in Batford, Warwickshire, England on June 28, 1878, William “Bill” Ivens came to Canada in 1896, working initially as a market gardener. In 1908, he married Louisa Davis and together they had four children. Ivens studied at Wesley College (now the University of Winnipeg) and the University of Manitoba, where he earned a Master’s of Arts degree and completed a thesis on Canadian Immigration, in 1909. In 1916, Ivens became a Methodist minister at McDougall Church, but was expelled in 1918 due to his pacifist and pro-labour views, which were perceived as being radical. Despite this, he continued to minister, establishing the first Labour Church in Winnipeg. That same year, Ivens became the editor of the Western Labor News, the official newspaper of the Winnipeg Trades and Labor Council, which would ultimately lead to his arrest during the General Strike.

During the strike, Ivens published special strike editions of the Western Labor News almost daily in order to keep strikers informed and provide the Strike Committee’s take on events as they unfolded. In addition to his editing job, Ivens regularly provided pro-strike sermons and church services in Victoria Park. These sermons and articles landed Ivens in jail on June 17 when he and several other leaders of the strike were arrested. He was charged with seditious libel and conspiracy, but was released on bail on June 20 under the condition he no longer spoke publicly about the strike. Beginning in January 1920, Ivens was tried, along with six other strike leaders for seditious conspiracy and committing a common nuisance.

During his trial, Ivens gave a twenty-hour address to the jury. On hour 14 of the address, Ivens had to be excused from court due to exhaustion caused by a family illness and the stress of the trial. He was excused Friday, March 20 and returned the following Monday, at which time he resumed the remaining six hours of his address. In his address, Ivens expressed that he should only be held accountable for his own actions, just as the other men who stood trial should not be held accountable for Ivens’ actions. He denied accusations that he intended to fuel a Bolshevik revolution and further denied claims that his Labor Church was a smokescreen set-up to preach about subversion and disorder. When stating that he had no seditious intent, Judge Metcalfe stated that Ivens did not have the right to deny it. Ivens ended his address requesting a “Not guilty” verdict, stating that only this outcome would “prove to the world that we stood for justice and liberty, not sedition” (Winnipeg Tribune, March 23, 1920).

On March 27, the trial ended with a guilty verdict and Ivens was sentenced to twelve months in prison for seditious conspiracy and six months for committing a common nuisance. The following month, he was granted a two-day parole to see his dying infant son and attend his funeral. He would lose a second child within the year. Ivens served his time at the Birch River prison farm, where he acted as head gardener. While serving his term, Ivens ran Provincially for the Dominion Labour Party and was elected to the Manitoba Legislature in June 1920. In August, Ivens was taken from the prison farm to see a physician. He required surgery, but the physician mentioned multiple times, unprompted, that Ivens’ health issue was not related to his work at the prison farm. Upon his release in 1921, Ivens continued to advocate for the labour movement in the Legislature, where he sat until he finally lost his seat in 1936. He was never able to regain his seat, but nonetheless continued to support and be involved with the Manitoba Co-operative Commonwealth Federation. Ivens died in California in 1957 at the age of 78.

Image Source: WCPI A0018-522. UWA.

Richard James “Dickie” Johns was born in Cornwall, England on May 6, 1888. In 1909, Johns emigrated to the United States, spent a few years in Colorado, and moved to Canada in 1912. A machinist by trade, Johns began working for the Canadian Pacific Railway in Winnipeg.

Politically, Johns was considered by many to be a radical and he had no qualms about it. He once said that he was proud to be a socialist and that if he was called a Bolshevik, so be it (Bumsted 1994, 99). On another occasion, he told James Winning, moderate President of the Winnipeg Trades and Labor Council, that radicals like himself would soon control the labour movement (Kramer and Mitchell 2010, 22-23). In 1917, he urged a general strike to protest national registration and conscription. Johns was a speaker at the Majestic Theatre meeting in January 1919, at which he expressed his belief that only by educating the working class could violent revolution be avoided. In March 1919, he was a delegate to the Western Labor Conference in Calgary and was elected to carry out the propaganda of the One Big Union (Bumsted 1994, 99).

During the General Strike, Johns wasn’t in Winnipeg. He was at first in Toronto, attempting to organize a general strike there. By the time a warrant was issued for his arrest on June 17, he was part of a negotiating committee for railway workers in Montreal. Despite his absence Johns was still perceived as a significant threat by the Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand. The Winnipeg Citizen labeled Johns as one of the “Red Five”, describing him as “one of the leading agitators” of the Winnipeg General Strike and, more generally, “one of the worst Red agitators in Canada” (Winnipeg Citizen, June 7 and 9, 1919). Johns was so busy with his affairs outside of Winnipeg that, by June 19, he was still unaware that a warrant was issued for his arrest. That day he attended his scheduled meeting with the Montreal Trades and Labor Council, much to their surprise.

In the end, Johns was brought back to Winnipeg to face his charges alongside six other strike leaders. He was defended by Ward Hollands, a choice he was later said to have regretted – not because he believed the outcome would have been different, but because he wished to speak for himself. Like most of his co-defendants, Johns was found guilty on all charges. Once the verdict was read, the men were permitted an hour with their families followed by an opportunity to confer with council. At this time, all seven co-defendants stood up, including A.A. Heaps, the only man acquitted of all charges. Johns took an amused tone and reminded Heaps “you are not a conspirator” (Winnipeg Tribune, 1920-03-29).

While serving his sentence in Stony Mountain and at the Birch River Prison Farm, Johns ran unsuccessfully for a seat in the Provincial Legislature. In March of 1921, shortly after his release, Johns stated at a meeting at the Board of Trade that his worst regret was the loss of “one year’s experience in the Winnipeg Labor movement” (Winnipeg Tribune, March 1, 1921). In later years, Johns became a vocational educator, teaching trade skills to future generations. He became Director of Technical Education for Manitoba and the first principal at Winnipeg’s Technical Vocational High School. He retired in 1953 and moved to British Columbia in 1960. Johns died in Victoria on August 26, 1970.

Image Source: Winnipeg Tribune Personality Files. UMASC.

William Arthur “Bill” Pritchard was born in England in 1888. In 1900, his father, James Pritchard, left for Canada. During a visit home in 1911, William was convinced to accompany his father back to Vancouver. His father was involved with the Socialist Party of Canada (SPC) and within a few days of his arrival in Vancouver, William became involved as well, becoming a member shortly thereafter. An active member of the party, Pritchard was the editor of the Western Clarion, a newspaper published by the SPC. Pritchard didn’t arrive in Winnipeg until June 12, 1919, several weeks into the General Strike. That day, he spoke to a crowd of strikers at Victoria Park, but left soon afterwards, heading back to his wife and three children in Vancouver. However, despite not being involved in the strike’s conception or even being in Winnipeg when it began, a warrant for his arrest was issued on June 17. The Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand considered Pritchard one of the “Red Five”, whom they considered the most dangerous Bolsheviks in Canada (Winnipeg Citizen, June 7, 1919). He was arrested two days later on a train in Calgary and brought back to Winnipeg.

Pritchard represented himself during the trials in January 1920, following William Ivens’ defense and preceding A.A. Heaps’. From March 23 to March 24, over the course of sixteen hours, Pritchard delivered an address to the jury in front of Judge Metcalfe. Pritchard was a strong orator, which the Winnipeg Tribune noted in a March 24 article that said Pritchard “established his reputation as perhaps the most brilliant and intellectual of the labor leaders in Canada”. His address drew a large crowd in the courtroom despite an ongoing blizzard.

On March 27, Pritchard was found guilty of all charges. Following the jury’s verdict, Pritchard asked whether he would have access to literature in prison, stating, “I cannot live without books” (Winnipeg Tribune, March 29, 1920). Pritchard served his sentence on a prison farm, where he did have access to many books and spent time working in the fields.

Upon his release, Pritchard returned to British Columbia and continued to work in politics and support labour causes. Following his appointment to Council in Burnaby, Pritchard went on to become Reeve in 1930. In 1981, Pritchard died, making him the last of the arrested strike leaders to pass away.

Image Source: Winnipeg Tribune, March 27, 1920. UML.

Born in Lanarkshire, Scotland in 1882 to a religious family, John Queen came to Winnipeg in 1906. He worked as a cooper and a driver for a laundering company until 1916 when he was elected to City Council as an Alderman for Ward 5 in the North End.

As Alderman, Queen championed several labour causes, including a more progressive tax system and benefits for returning soldiers. During the civic employee strike in 1918, he generally voted in favour of reconciling with the strikers and said to them outright that the working class should dictate all aspects of their employ (Johnson 1978, 95). Queen was also active in the broader Winnipeg labour movement. He was a member of the Social Democratic Party, a business agent and advertising manager for the Western Labor News, and co-founder of the Winnipeg Socialist Sunday School. On December 22, 1918, Queen chaired the infamous Walker Theatre meeting, at which he was reported to have closed the meeting by calling for cheers for the Russian Revolution. Despite his fiery rhetoric, Queen was a moderate: he was a social democrat and did not support the One Big Union.

Queen played an active role in the General Strike. He was on the ad hoc committee that directed the strike prior to the formal Strike Committee being formed on May 21 (Masters 1973, 45). He also advocated for the strikers in his capacity as an Alderman. With Aldermen A.A. Heaps, and three others, he became part of an inadvertent and unofficial pro-strike party – Council votes almost always coming down to a 9 to 5 result against them. Queen was in an especially awkward position as Alderman, as he was a member of the City’s Special Food Committee, which oversaw the delivery of milk and ice after creamery and delivery workers were called out on strike.

On June 17, Queen was arrested along with several other strike leaders. His trial began in January 1920, in which he represented himself. He was charged with seditious conspiracy, was found guilty on March 27, and was sentenced to one year in prison.

Incarceration did not hamper Queen’s political career. While still in prison, he was elected as a Member of the Legislative Assembly where he sat between 1921 and 1940 as a member of the Independent Labour Party and, later, the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation. At the same time, he also served as Mayor of Winnipeg from 1935 to 1936, and from 1938 to 1942. While an MLA and Mayor he advocated for progressive taxation and housing reform.

Queen died on July 14, 1946 and was buried at Brookside Cemetery.

Image Source: COWA. Art Collection (A01068)

For more information on John Queen’s involvement in the strike, see Who: Government & Politicians

Robert Boyd “Bob” Russell was born in Glasgow, Scotland in October, 1889, and came to Winnipeg in 1911. Russell worked as a machinist for the Canadian Pacific Railway and was an active union organizer, as well as a member of the Socialist Party of Canada. In 1918, he became the first secretary of the Metal Trades Council and was prominent in negotiations between the Council and its members’ employers. That same year, he led a campaign to remove Trades and Labor Council president Fred Tipping from office and unsuccessfully ran to replace him, losing to James Winning. Russell attended the Walker Theatre meeting in December 1918, where an undercover military sergeant noted that Russell had condemned Canada’s military presence in Russia and expressed his support for the Russian Revolution. In March of 1919, Russell traveled to Calgary to attend the Western Labor Conference as one of over two hundred delegates. During this conference, Russell supported the One Big Union. That same month, Russell attended a meeting set up by Mayor Gray to arbitrate disputes between labour their employers. The meeting was also attended by bakery owner and future Citizens’ Committee member Ed Parnell. The two men disagreed on a several points, leading Russell to hand Parnell a copy of Vladimir Lenin’s The Soviets at Work and tell him that he’d understand after reading it (Kramer and Mitchell 2010, 92).

When the General Strike began, Russell was elected as a member of the Strike Committee’s executive, as well as a member of the temporary committee that preceded it. Along with James Winning, Russell acted as a representative of the Strike Committee during mediations with City Council, the Iron Masters and the Builders’ Exchange, and the Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand. On June 17, 1919, Russell was arrested at his home early in the morning while it was still dark and while he was still sleeping. His house was searched for literature and papers deemed to be seditious. Despite this, Russell was appointed secretary-treasurer of the Winnipeg Trades and Labor Council while awaiting trial.

Russell was tried separately and a few months earlier than the other strike leaders. His trial began on November 25, 1919, and went on for over twenty days. During his trial, Russell was defended by Edward Bird, Robert Cassidy, Wallace Lefeaux, and E.J. McMurray. The prosecution was made up of A.J. Andrews, James Coyne, Isaac Pitblado, Travers Sweatman, and Sid Goldstine, the former four of which were members of the Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand. The prosecution used morally, if not legally questionable means to pack the jury in their favour.

The jury was presented with over 700 exhibits by the prosecutions. For his defence, Russell’s lawyers argued that their defendant could not have conspired with the other arrested strike leaders, as many of the accused did not share the same political views and had further publicly opposed and even ran against each other during election campaigns. Consequently, the only point of agreement between them, and the motive behind the strike, was to gain collective bargaining and higher pay. In the end, Russell was found guilty on all counts on December 24, 1919, and was sentenced to two years in prison, though he was released on parole after serving approximately 50 weeks of his sentence on December 11, 1920.

Following the strike, Russell unsuccessfully ran for various Provincial and Federal seats throughout the 1920s and served as the leader of the One Big Union in Winnipeg. Russell died at his home in St. Vital on September 25, 1964. He is buried at Chapel Lawn Memorial Gardens in the parish of St. Charles. Following his death, the R.B. Russell Vocational High School, on Dufferin Avenue, was named in his honour.

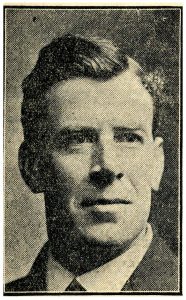

Image Source: Winnipeg Tribune, December 1919. UML.

James Winning was born in Cambuslang, Scotland in 1881. A bricklayer by trade, Winning joined the London Order of Bricklayers in 1902 and came to Winnipeg in 1906. In Winnipeg, he joined the Manitoba Bricklayers’, Masons’, and Plasterers’ International Union Local Number One and quickly rose through the ranks. He was also prominent on the Building Trades Council and became the president of the Winnipeg Trades and Labor Council in 1918. In terms of politics, he was a moderate and a traditional trade unionist, but this was not always the case. Prior to moving to Winnipeg, Winning used to sell copies of Robert Blatchford’s Clarion and supported Keir Hardie, a socialist Member of Parliament (Masters 1973, 46). As a moderate, he at times butted heads with the more radical elements in the labour movement, such as R.J. Johns, who once admonished Winning that radicals would soon control the labour movement (Kramer and Mitchell 2010, 22-23).

As president of the Winnipeg Trades and Labor Council, Winning presided over the referendum that would determine whether to call a general strike. When the strike was called, Winning was one of five on an ad hoc committee that directed the strike before the formal Strike Committee was established on May 21, after which Winning served on the new committee’s executive. Along with R.B. Russell, Winning often represented the Strike Committee during settlement negotiations. Though negotiations generally didn’t amount to much, Winning did have success when negotiating with former Attorney General Hudson and Herbert Symington, who were negotiating on behalf of the Province against the wishes of the Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand. In these negotiations, Winning was able to secure a promise that, once the strike was settled, the Province would launch a commission (the Robson Commission) to investigate the causes and effects of the General Strike (Kramer and Mitchell 2010, 186). This was one of the few concessions the Strike Committee gained by ending the strike.

At one of the hearings held by the Robson Commission in Winnipeg, Winning testified as to what, in his mind, were the causes of the strike, which he attributed to poor working conditions, low wages, high costs of living, the increased cognizance of workers to societal inequality, and job insecurity, the latter of which Winning referred to as the “greatest nightmare of the working class” (Robson Commission, Peel’s Prairie Provinces, page 6). The commissioner, H.A. Robson, was so satisfied with Winning’s take that he quoted his testimony at length in his report and referred to Winning’s words frequently.

In 1922, Winning ran unsuccessfully for a seat in the Manitoba Legislature. He joined the Provincial Minimum Wage Board prior to the strike, in 1918, and held that position until 1941. He passed away on November 26, 1951 and was buried at Elmwood Cemetery.

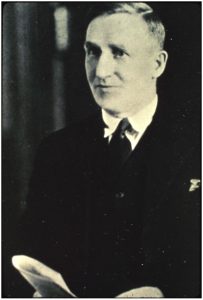

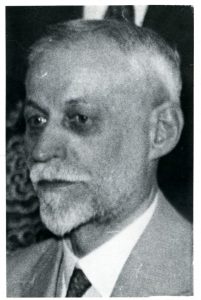

Image Source: Winnipeg Tribune, July 8, 1922. UML.

James Shaver Woodsworth was born to a Methodist family in Islington, Ontario in 1874, the eldest of James Woodsworth and Esther Josephine Shaver’s six children. His father’s work as a Methodist minister took the family to Brandon in the 1880s. James Shaver Woodsworth would later follow in his father’s footsteps, becoming a Methodist minister after completing his studies at Wesley College, Victoria College (Toronto), and Oxford University. Woodsworth returned to Manitoba and settled in Winnipeg. As a strong advocate for social welfare and pacifism, Woodsworth’s views were well aligned with the social gospel movement, leading him to work with the immigrant community in Winnipeg’s North End through the Methodist All People’s Mission. He was a superintendent for the organization from 1907 to 1913. In his capacity as a member of the General Ministerial Association (GMA), an organization affiliated with the Winnipeg Trades and Labor Council, Woodsworth acted as a delegate and a committee member for the WTLC

In the mid-1910s, Woodsworth moved to Vancouver, and, in 1918, finding himself in opposition with the Methodist Church’s views on the First World War, left the church to take up work as a longshoreman, becoming a member of the International Longshoremans’ Association. He did not return to Winnipeg until the strike was already underway, in June of 1919, as part of a national speaking tour. During his time in Winnipeg, he spoke on numerous occasions in Victoria Park on topics such as the rights of women and equal pay for equal work. Some of Woodsworth’s speaking events were used to raise funds to feed women who were on strike themselves or whose husbands were. During his time in Winnipeg, Woodsworth addressed strikers through articles in the Western Labor News, in which he defended immigrants, stating that the “strike is not the work of alien enemies. It is positively criminal for leaders of public opinion to thus deceive the people” (Western Labor News, June 12, 1919). He further clarified his role in the strike: “I have no official connection with the strike. I had arranged to visit Winnipeg weeks ago before the strike was called” (Western Labor News, June 12, 1919). This, however, did not prevent him from being identified as one of the strike’s leaders.

Following the arrest of the Western Labor News’ editor, William Ivens, Woodsworth briefly took over the position. On June 23, shortly after taking over from Ivens, Woodsworth was, in the company of Fred Dixon and on their way to notify the Strike Committee that the Western Labor News had been suppressed, arrested near the McLaren Hotel on Main Street. Dixon would take over the role of editor, until his own arrest a few days later. Both he and Woodsworth were charged with seditious libel. Woodsworth was further charged with speaking seditious words and being part of an unlawful assembly. The latter charge was dropped soon after, while the charge for seditious libel and speaking seditious words were dropped in February and March of 1920, respectively.

Following the strike, Woodsworth became a prominent politician, elected in 1921 as a Member of Parliament for Winnipeg North Centre, representing labour. He played a key role in pushing through legislation that established Canada’s Old Age Pension Plan in 1926. In 1932, Woodsworth became the first leader of the newly created Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (the forerunner of the New Democratic Party). He held this position until the outbreak of the Second World War, when his pacifist views made him unpopular. Despite this, he retained his seat in Parliament until his death on March 21, 1942.

Image Source: Winnipeg Tribune Personality Files. UMASC.

![OP6-5-1_Flye (1) Thomas Flye. Source: City of Winnipeg Archives. Photograph Collection [OP6 File 5].](https://1919strike.lib.umanitoba.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/OP6-5-1_Flye-1.jpg)