Returned Soldiers

The Winnipeg General Strike occurred shortly after the end of the First World War, when many Winnipeggers were adjusting to postwar society. In particular, soldiers who returned from the war – “returned soldiers” or “returned men” – struggled to adjust to the harsh reality they found back home. They had left their jobs to fight for the Commonwealth and expected those jobs to be waiting for them when they returned. But this was not always the case. Winnipeg’s population had increased and, though many jobs, such as the production of munitions and armaments, had been created to support the war, peace meant that these jobs no longer existed. Consequently, soldiers returned to a Winnipeg with high unemployment, a high cost of living, and an outbreak of Spanish Influenza that left many with an uncertain future.

Many returned soldiers found immigrants working in their old positions and blamed them for their struggles. Furthermore, having spent the last four years fighting against the German and Austro-Hungarian Empires, as well as the Bolsheviks in the former Russian Empire, they perceived any persons from Central or Eastern Europe as enemy aliens.

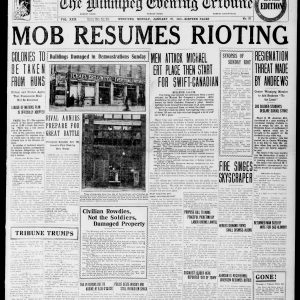

In early 1919, these tensions came to a head, as a group of men, many of whom were said to be returned soldiers, started a riot targeting establishments owned or staffed by immigrants, including the Minneapolis Dye House, owned by future strike leader Samuel Blumenberg. The two-day riot was said to have been started when returned soldiers learned that a socialist meeting was planned to mourn the deaths of German socialists Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg. In Market Square, the rioters began to force so-called enemy aliens to kiss the Union Jack flag, beating those who refused. Over 30 people were injured as a result of these events. Veterans continued on to establishments where immigrants were employed, such as the Swift Meat Packing Plant, and demanded that they be fired. Though returned soldiers did not always agree with each other’s political views, they were largely of one mind when it came to immigrants and enemy aliens, whom they did not welcome in Winnipeg.

When the General Strike broke out, both pro and anti-strike groups wanted to win the support of returned soldiers. For their service, veterans were greatly respected in Winnipeg and across Canada and held significant value as symbols of patriotism and moral integrity. Thus, gaining the support of this group would allow either side to sway public opinion in their favour.

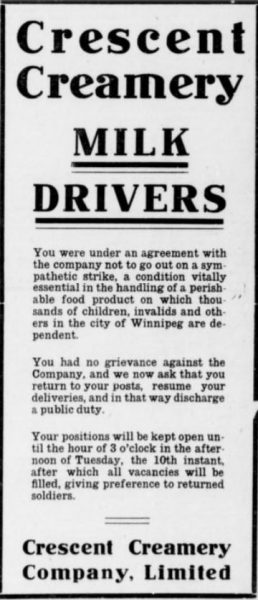

To win over the veterans, the Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand emphasized the interference of enemy aliens and Bolsheviks in the strike, and further pointed to the war records of some strike leaders – particularly those who were pacifists and opposed the war. Strike leaders such as Samuel Blumenberg, a Romanian immigrant who identified as a socialist and a pacifist, did not win the favour of many veterans. Employers further tried to sway veterans to their side, often advertising employment to replace striking workers and giving priority to returned soldiers.

On the pro-strike side, it was largely understood that being pro-immigration would not sway veterans. For this reason, the Strike Committee did not allow immigrants from “enemy” countries onto the committee. In addition, the Winnipeg Trades and Labor Council answered the question “Are the strikers defending UNDESIRABLE aliens?” in its publication, Western Labor News: “Most assuredly they are not. It is an insult to men who have fought over there to say that they are now aiding undesirable enemies” (Western Labor News, June 7, 1919). The newspaper further assured readers that strikers would support the authorities in efforts to deport aliens. For or against the strike, the most effective method of reaching the soldiers was by soliciting the support of a number of key veteran organizations in Winnipeg.

The Strike Committee and the Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand both attempted to gain the undivided support of the Great War Veterans’ Association (GWVA), the Army and Navy Veterans Association, and the Imperial Veterans of Canada, but to no avail. Though individual members of these associations held their own views about the strike, the organizations overall generally maintained a neutral stance. In some cases, this policy of neutrality did not sit well with members. The GWVA, for example, was asked by one of its members – Captain F.G. Thompson – to publicly declare itself as an anti-strike organization. When the GWVA refused, Thompson formed his own anti-strike organization: the Loyalist Returned Soldiers Association. On the other side, under Chairman Roger Bray, some veterans joined the Returned Soldier Strikers in support of the strike. Ultimately, returned soldiers who were previously united in war, found themselves on opposing sides of the strike.

For more information on veterans and “enemy aliens”, see Who: Racialized Communities.

Pro-Strike Veterans

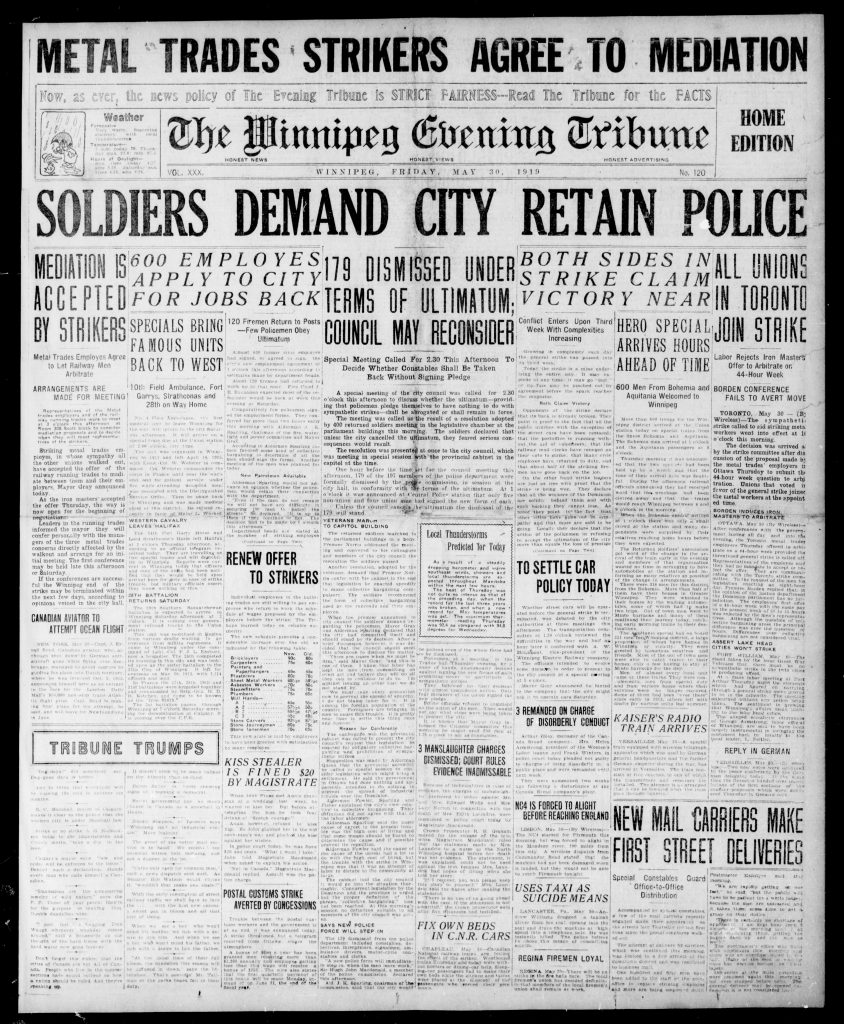

For some veterans, it was clear upon their return from Europe that big business had profited from the war at the expense of the workers. They saw the strike as a means to gain employment, higher wages, the right to collective bargaining, and better working conditions. Parades made up of thousands of pro-strike veterans often rallied to apply pressure on their governments. Weather permitting, a “Soldiers’ Parliament” met in Victoria Park every morning at 10 am (near the end of the strike, these meetings were held at 7:30 pm) to listen to committee reports and decide how to proceed. Furthermore, veterans frequently marched to the Manitoba Legislative Building to visit Premier Norris and demand legislation be enacted to support their cause. When these requests went unanswered, they demanded the government resign – a call that went unanswered by the Premier. With many veterans employed by the police force, returned soldiers who were on strike or sympathetic to it further threatened serious consequences if the City did not reconsider its ultimatum issued to police officers that demanded they sign an anti-strike loyalty pledge (the Slave Pact). The deadline for the ultimatum was later extended – a decision which may have been in part influenced by the statement made by returned soldiers.

On other occasions, Returned Soldier Strikers and strike sympathizers lead marches to intimidate those opposed to the strike: the Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand. On June 4th, and June 5th, pro-strike veterans marched down Wellington Crescent and into Fort Rouge respectively, where many members of the Citizens’ Committee lived. The parade prompted the residents of Crescentwood to organize volunteer patrols and set-up a secondary phone line in the event that pro-strikers cut the first.

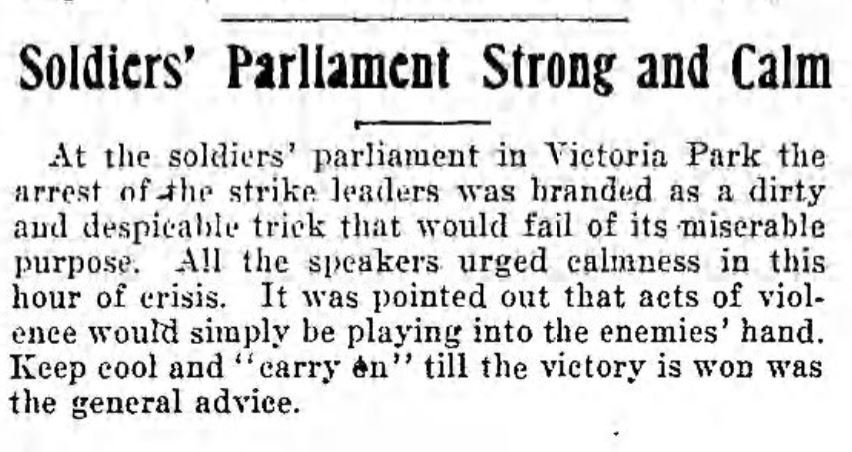

Through such demonstrations, pro-strike veterans became a visible force throughout the strike and, as such, their spokesperson Roger Bray, became a target for authorities. In fact, a police spy – Constable W.H. McLaughlin – described Bray as Winnipeg’s most dangerous man. On June 17, Bray, alongside other strike leaders, was arrested. A Soldiers’ Parliament was held later that day, where the arrests were described as “a dirty and despicable trick” and soldiers were asked to keep calm (Western Labor News, June 17). A few days later, on June 20, the Returned Soldier Strikers gathered at Market Square, under the direction of John Farnell, who stepped in as spokesperson following Bray’s arrest. In protest of the arrests, the veterans decided to hold a silent parade the following day, on June 21, and follow it with a march to the Royal Alexandra Hotel, where Minister of Labor Gideon Robertson was staying, to discuss the arrests with the Federal representative.

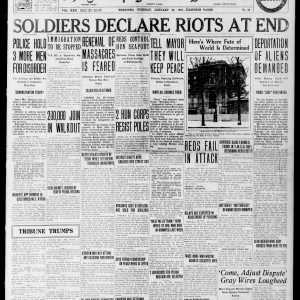

On June 21, in the hours prior to the parade, government representatives, including Mayor Gray and Federal Minister Gideon Robertson, met with representatives of the Returned Soldier Strikers – F.H. Dunn, John Farnell, and J.A. Martin – to persuade them to cancel the parade. Their request was rejected and the parade proceeded. In the early afternoon, the silent parade quickly escalated into a riot now known as Bloody Saturday. Returned soldiers found themselves once more engaged in a war. But while they had previously fought side-by-side, the pro-strike veterans found themselves in conflict with the Special Police and volunteer militia, made up of many veterans opposed to the strike.

Anti-Strike Veterans

Anti-strike returned soldiers were made up, in part, by members of Winnipeg’s middle class. However, the fear that Bolshevism was at the heart of the strike further convinced returned soldiers from all walks of life to oppose the strike. These men had fought for their country and the Commonwealth for the last four years and though they might have adopted a neutral or pro-strike view initially, propaganda eluding to enemy ideologies directing the strike were effective in soliciting the support of many returned soldiers. Though they shared common concerns with those who supported the strike – rising inflation, poor working conditions, low wages – this common ground was eclipsed by matters they considered more imperative: the deportation of “enemy-aliens” and the total suppression of Bolshevism.

The first anti-strike parade led by returned soldiers was held on June 4. Two days later, on June 6, the Loyalist Returned Soldiers Association was formed, welcoming anti-strike veterans to its ranks. The association was founded by Captain F.G. Thompson, who acted as a GWVA delegate to the Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand and, consequently, the organization was often perceived as being closely tied to the Citizens’ Committee.

The Loyalist Returned Soldiers Association helped oppose the strike by providing volunteer policemen, firemen, and streetcar operators, while many others joined the militia. In fact, the Citizens’ Committee actively played a role in this process. With the interruption of street car services, the Citizens had organized cars to transport volunteers to and from work, and further helped returned soldiers get home. The latter arrangement allowed drivers to recruit returned soldiers into the militia and direct them to Fort Osborne Barracks. This move increased the risk of rioting and violence. Even before Special Police were sworn in, it was no secret that confrontations between pro and anti-strike veterans could become violent. The January riots had proven that veterans were unpredictable and sometimes uncontrollable. Pitting them against each other on opposite sides of the strike created a powder keg that could go off at any time. During the strike, on days where parades were planned by both pro and anti-strike veteran groups, efforts were made to ensure these demonstrations never crossed path. Once anti-strike veterans were given the opportunity to wield bats against strikers and strike sympathizers as Special Police, the risk of violence quickly escalated. This all came to a head on Bloody Saturday, which ended in a 10 minute battle in Hell’s Alley – named because the battle which occurred there had, according to returned soldiers, “trench action in France beaten” (Winnipeg Tribune, June 23, 1919).