Government & Politicians

Civic Government

During the General Strike, Winnipeg’s municipal government was divided. City Councilors were at odds with one another, some for and some against the strike; most City employees had walked off the job; and City departments were just trying stay operational with the few employees who remained.

City Council was an ideological battleground at this time, as it had been during the 1918 civic employees strike. Two Aldermen, A.A. Heaps and John Queen, were strike leaders arrested on June 17, one, E. Robinson, was Secretary of the Trades and Labour Council that organized the strike, and two others, W.B. Simpson and J.L. Wiginton, generally voted on the side of labour. On the other side, Aldermen such as J.K. Sparling and F.O. Fowler had ties to the Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand and, along with seven other anti-strike Aldermen, generally outvoted the five who were pro-strike. While he initially tried to bring both the strikers and the Citizens’ Committee to the table for negotiations, Mayor Charles Gray became less sympathetic to the strikers as time went on. Gray was not necessarily enamoured with everything the Citizens’ Committee did, but both he and some of the anti-strike Aldermen consorted with them on a number of occasions and provided testimony during the trials of the strike leaders.

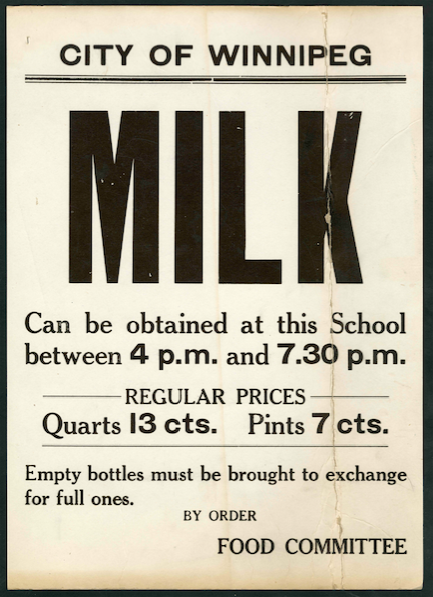

City departments were primarily concerned with returning to business as usual. Department managers had less staff than was required to perform their duties and struggled with keeping City services running. While not all departments lost a significant number of employees – some lost none – others were forced to rely on volunteers and extra work from those employees who remained. The volunteers were acquired through various means. In some cases, volunteers were organized by the Citizens’ Committee. On June 4, when bakery and creamery workers were called out on strike, the City took it upon itself to fill the gap. A Special Food Committee was organized to oversee the distribution of milk, ice, and food to schools around the city where people who had lost their usual delivery services could purchase what they needed. When the strike ended, volunteers and those who didn’t go on strike were often rewarded or requested compensation themselves for services rendered.

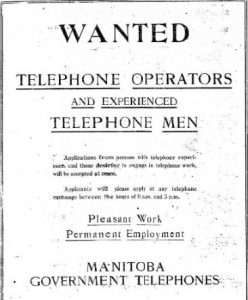

In some cases, new employees were hired to fill the positions of those who went on strike. Both new employees and those who didn’t go on strike were forced to sign what was called the Slave Pact, a pledge of loyalty to the City that forbade City employees from engaging in sympathetic strikes or being part of larger scale unions. This pact remained in effect until 1930. After the strike ended, most City employees attempted to return to their positions, but many were not welcomed back or found their positions had been filled. Some moved on, while others fought to reacquire their jobs, often appealing to City Council, Council Committees, or the Mayor’s Office. Older employees in particular were affected by this, as it was no simple task for them to start their lives over. Even those that were taken back had to deal with an uncertain future as, in terms of their pensions, they were considered new employees. This was remedied in 1922 when an amendment to the pension by-law gave those who went on strike credit for their service prior to the strike.

F.O. Fowler (1861-1945)

Frank Oliver Fowler was born on December 14, 1861, in Wingham, Ontario, where he worked in a saw mill until moving to Brandon in 1881 to farm. Prior to moving to Winnipeg in 1902, Fowler had a successful political career: he was a Reeve of the Rural Municipality of Oakland from 1892 to 1894, and was elected to the Provincial Legislature as a Liberal in 1899. After coming to Winnipeg, he worked as the Secretary-Treasurer of the North West Grain Dealers’ Association and managed the Winnipeg Grain and Produce Clearing Association.

Fowler was elected to City Council in 1908, representing the fairly wealthy Ward 2. As a member of the Manitoba Club, a founding member of the St. Charles Country Club, and a member of other associations of Winnipeg’s economic elite, Fowler used his position as Alderman to support the interests of business and limit the powers of collective bargaining. During the 1918 civic employees strike, Fowler convinced a slim majority of Council to amend a tentative agreement with the strikers that forbade them from taking any strike action in the future. The “Fowler Amendment” enraged the strikers, leading to further walkouts. The amendment was repealed as part of the strike settlement.

Fowler was decidedly against the General Strike and conferred with the Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand on more than one occasion, often siding with their viewpoints. On May 26, he seconded a motion that required firemen to sign the Slave Pact. On June 9, Fowler put forward a motion that extended the Slave Pact to all Civic employees. After the strike had ended, Fowler continued on as Alderman for Ward 2 and became Mayor by acclamation for a short time in 1922 after the death of Mayor Parnell. Fowler passed away on February 18, 1945, and was buried in Elmwood Cemetery.

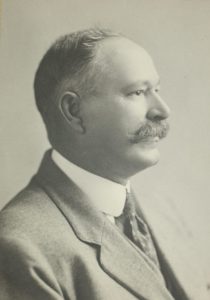

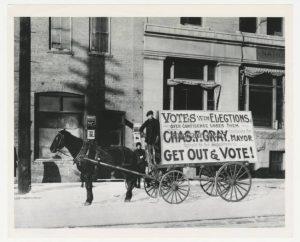

Charles Frederick Gray (1879-1954)

Charles Frederick Gray was born in London, England in 1879. In 1894, Gray left his home to apprentice as a midshipman and, in 1897 he came to Canada, settling in Nelson, British Columbia, where he worked as a smelter and studied electrical engineering. He began working at various engineering firms that took him all over North American and Britain, eventually bringing him to Winnipeg in 1911 to work on a project in Point du Bois, Manitoba. Gray stayed in Winnipeg to open his own consulting firm and became involved in civic politics, being elected to the Board of Control in 1917 and 1918.

During the Winnipeg civic employees strike in 1918, Gray’s stance towards the strikers vacillated. He initially worked with the strikers towards a negotiated settlement, but when the settlement was presented in Council, he voted in favour of an amendment proposed by Alderman F.O. Fowler that forbade civic employees from striking in the future, calling Fowler’s speech “the strongest speech I have heard in this council, bar none”, and that he believed “firemen should not strike, nor the police – they should not have the power” (Johnson 1978, 117).

Gray similarly vacillated in his response towards the 1919 strike. On the one hand, though he was never in favour of the strike, he attempted on multiple occasions to negotiate a settlement between the City, the strikers, the Iron Masters, and the Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand. On the other hand, he publicly critiqued the strike as undermining the City’s – and his – constituted authority.The Citizens’ Committee was involved in undermining his authority as well, however. Gray was initially asked to join the Citizens’ Committee, but declined, stating that he was supposed to represent all of Winnipeg (Kramer and Mitchell 2010, 269). As a result, the Citizens frequently went behind his back and over his head to achieve their goals. When Acting Federal Minister of Justice Arthur Meighen and Minister of Labor Gideon Robertson arrived in Winnipeg to assess the strike, they met with the Citizens immediately, but only met with Gray two days later; as well, Gray wasn’t invited to the meeting on June 16, at which the Citizens, the Province, the Federal Government, and even Gray’s Acting Chief of Police discussed which of the strike leaders should be arrested.

But it was the loss of his authority on the streets that Gray really bristled against. When the police arrested a Dominion operative, Gray rushed to try to stop the arrest, but was hounded by a group of strikers who either assaulted the Mayor or attempted to protect the police from him, depending on which paper reported it. He issued proclamations against public assemblies on three separate occasions and each time was ignored. On June 20, Gray explicitly forbade a parade that pro-strike returned soldiers had planned for the following day – Bloody Saturday. In what could be construed as a threat of violence, Gray admonished that “any women taking part in the parade do so at their own risk” (Manitoba Free Press, June 21, 1919, page 1). Last minute negotiations took place the next morning, but there was no resolution, and the parade began in spite of Gray’s orders. As the crowd began to overturn a streetcar operated by strikebreakers, Gray read the Riot Act, after which shots were fired by the Royal Northwest Mounted Police as they charged the crowd. Gray rushed to the Osborne Barracks to call for militia support from General Ketchen. Trucks with mounted Lewis Machine Guns arrived on the scene and the crowd dispersed. In the following City Council meeting on June 23, pro-labour Aldermen E. Robinson and W.B. Simpson questioned Gray about the events on Bloody Saturday and his part in them.

After the strike had ended and the preliminary hearing of the arrested strike leaders began, Gray testified that City employees had, in his view, violated their contracts by walking out, and testified against Aldermen Heaps and Queen, claiming that they had done everything in their power as Aldermen to disrupt City services. Gray was reelected mayor for another term, after which he returned to his consulting firm. He founded the Cutty Sark Club and the On-To-The-Bay Club, and was credited with developing the rail line to the Hudson’s Bay. In 1941, Gray and his family moved to Ashland, British Columbia. He died in Victoria on June 27, 1954.

John Kerr Sparling (1872-1941)

J.K. Sparling was born in Montreal in 1872 to Methodist Minister J.W. Sparling, who moved to Winnipeg with his family in 1888. In 1898, the younger Sparling went to the Yukon and practiced law during the Klondike Gold Rush. Returning to Winnipeg in 1906, Sparling started a law firm with his brother before becoming an Alderman for Ward 1 in 1917.

Ward 1 was a particularly wealthy ward south of the Assiniboine River, and as such, Sparling was primarily representing Winnipeg’s Anglo-Saxon business elite, of which he himself was a member. In 1918, he prevented a German born chauffeur from obtaining his license due to remarks the latter had made about American involvement in the First World War. That same year, he voted in favour of Alderman Fowler’s amendment to Council’s settlement with striking civic employees that removed their right to strike.

Sparling played a significant role during the General Strike. He had a close relationship with the Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand, conferred with them often, and brought their motions before Council. Sparling put forward a motion on May 26 that required firefighters to sign the Slave Pact and on June 9 put forward a motion urging employers to go back to business as usual. Sparling’s most important role, however, was that of Chairman of the Board of Police Commissioners. On May 29, Sparling gave the police an ultimatum: sign the Slave Pact or be dismissed. While some did end up signing the pact, more than 200 refused and were dismissed on June 9, replaced by Special Police.

Sparling was questioned as part of the preliminary hearings of the strike leaders who were arrested on June 17. More specifically, he was questioned about the role of the Special Police and about whether or not it was the Police Commission, rather than the police, who broke their contract by insisting the Slave Pact be signed. In response, he admitted that the ultimatum was issued to prevent sympathetic strikes. After the strike, Sparling ran for mayor in 1922, but was defeated by pro-labour candidate Seymour Farmer. Though his political career ended, he remained active in public life, serving on the University of Manitoba Senate, as well as the Board of Wesley College. He died on November 19, 1941, and was buried in the Elmwood Cemetery.

Other City Officials

For more information on Civic Government, see Where to learn about City Hall during the strike.

Provincial Government

Tobias Crawford Norris

T.C. Norris was born and raised in Ontario in 1861. Working as a farm labourer throughout his early years, Norris later settled in Manitoba and purchased land near Brandon to farm. He expanded his experience by working in business and becoming an auctioneer and in 1896, Norris entered the political realm, winning a seat as the Liberal MLA for Lansdowne. He lost his seat in 1903 but was re-elected in 1907. Three years later, in 1910, he had worked his way up to becoming the leader of the Liberal Party. In 1915, Norris was elected Premier of Manitoba following an investigation brought on by future strike leader Fred Dixon into possible corruption by Premier Rodmond Roblin’s Conservative government. After it was found that the government had committed fraud and overpaid contractors for the new Legislative building in order to receive kickbacks, Premier Roblin resigned and the Liberals, under Norris, took power.

Norris’ position as Premier began in the midst of the First World War and though this in itself made for an interesting start to his career as Premier, Norris would see Manitoba through many more milestones and historical moments. In 1916, Manitoba became the first province to grant women the right to vote; prohibition legislation was passed in the midst of the temperance movement; in 1918, after four years at war, Manitoba was transitioning into a post-war period; And, in 1919, the world would look to Manitoba’s capital as Winnipeg became the centre of the most famous strike in Canadian history.

During the Strike, Norris generally expressed a neutral view on the strike, but was favourable towards labour more generally. He did not wish to be involved, but his role as Premier made this difficult. Though he often tried to dismiss the issue as a Federal one that would be dealt with by the Canadian government, certain issues were clearly within the Provincial jurisdiction.

When Provincial employees went on strike, Norris was forced to issue an ultimatum, threatening striking employees with the loss of their jobs if they did not return to work. Norris was open to negotiations, but insisted that these could only occur once the strike was called off. Neutrality did not work for Norris. Pro-strike veterans marched to parliament frequently, demanding meetings with the Premier and threatening to force an election if the Premier did not act. As the Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand realized that the Provincial Government adopted a more neutral stance on the strike, they turned to the Federal Government. While this is what Norris had sought during much of the strike, it caused some tensions. The June 17 arrests, for example, may not have happened without Federal involvement. As arrest warrants were ready to be issued, Norris requested from Gideon Robertson, Minister of Labour, that the warrants not be issued as the Central Strike Committee was on the verge of meeting to discuss ending the strike. Norris believed that by arresting the strike leaders, they would risk jeopardizing the potential end of the conflict. Unfortunately, Federal representatives believed that even if this was true and the strike was about to be called off, its leaders would still have to be arrested, and so, the arrests went forward. In commenting on the arrests, Norris was quoted by the Winnipeg Tribune as stating “Just leave us out of it” (Winnipeg Tribune, June 17, 1919).

In the aftermath of the strike, Norris appointed Judge Robson to investigate the causes and impact of the strike in Winnipeg. The Robson Commission found no evidence that the strike was rooted in a Bolshevik or enemy alien conspiracy. Norris’s government further helped to establish the Joint Council of Industry which would study working conditions and disputes and propose legislation based on their findings. In the provincial election that followed the strike, it was clear that the dynamics of the Legislature had been altered by the events of 1919. While the votes historically went to the more established, traditional parties (the Liberals and Conservatives), the results of the 1920 election showed that these parties held less relevance for many, as the labour candidates and independents won 15 seats, collectively holding more than the Conservatives, but not quite surpassing the Liberals’ 21 seats. In the following election of 1922, the Liberals lost power to the Conservatives under the leadership of John Bracken, and while Norris lost his position as Premier, he maintained his seat in Landsdowne and title as leader of the Liberal party. He briefly left his seat to run Federally but, following an unsuccessful campaign, he returned to the Provincial Legislature until 1927, when he resigned to take an appointment with the Board of Railway Commissioners. In 1936, shortly after his term in this position ended, Norris died suddenly in Toronto.

Thomas Herman Johnson (1870-1927)

Born in Iceland in 1870, Thomas Herman Johnson (Tómas Hermann Jónsson) came to Manitoba in 1879, settling in Gimli. He was admitted to the Manitoba Bar in 1900 and was elected as a member of the Legislative Assembly in 1907. Johnson twice defeated future Citizens Committee of One Thousand member A.J. Andrews in provincial elections, once in 1910, when he defeated Andrews by just forty votes, and once in 1914, when he defeated Andrews by 1,050 votes. Johnson was a cabinet minister in Premier Norris’ Liberal government, holding positions as the Minister of Public Works from 1915-1917, the Minister of Telephones and Telegraphs from 1917-1922, and the Attorney General from 1917-1922.

As Attorney General, Johnson was ultimately responsible for deciding whether or not to prosecute strikers or their leaders, but throughout the strike, Johnson refused to commit either way, saying only that he would consider making arrests, and making several vague promises that at some point the strike’s leaders would be punished (Kramer and Mitchell 2010, 144). He did, however, create a Special Crown Prosecutors Department specifically to prosecute strikers. Johnson met with Ministers Arthur Meighen and Gideon Robertson on multiple occasions and attended several other meetings about settling the strike, but did little to exert his authority.

During R.B. Russell’s trial, the defense called Johnson to the stand and asked him to definitively answer whether or not the department considered the strike to have broken any laws and whether or not the department was paying for the Citizens’ prosecution of Russell. A.J. Andrews successfully objected to both lines of questioning and Johnson escaped having to answer (Kramer and Mitchell 2010, 301). However, Johnson was asked similar questions by Fred Dixon in the Legislature on February 16, 1920, forcing him to finally admit that, though he allowed the Citizens to prosecute the strike leaders, they were not doing so at the behest of his department (Ibid).

Johnson retired from politics in 1922 and returned to practicing law in the private sector. During his tenure in the Legislature, he advocated progressive legislation such as prison reform and workmen’s compensation. He was awarded the Order of St. Olaf and the Order of the Falcon by the kings of Norway and Denmark, respectively. Johnson died in Winnipeg on May 20, 1927.

Robert Graham (1870-1951)

Robert Blackwood Whidden Graham was born in Brookfield, Nova Scotia, in 1870. He was educated at Dalhousie University and was called to the Nova Scotia Bar in 1893. Graham came to Manitoba in 1897 and settled in Killarney, where he worked as a store clerk for six years before moving to Winnipeg in 1903 to work as an accountant for the Department of the Attorney General. He was called to the Manitoba Bar in 1906, was appointed Assistant Deputy Attorney General in 1908, and, three years later, he became Deputy Attorney General. In 1913, Graham resigned to practice law privately, only to return to the department that same year as Crown Prosecutor for the Winnipeg Police Court.

When the General Strike began, Graham was unconvinced that it was a significant threat. He claimed that most cases were contrived and that all they really amounted to were shouts of “abuse and empty threats” (Kramer and Mitchell, 81). As such, he dropped many strike related cases that came before him. This put him at odds with both the Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand and his own department. Though Attorney General T.H. Johnson was generally ambivalent and non-committal in his response to the strike, he nonetheless undermined Graham’s position by appointing Hugh Phillips, Graham’s Assistant Crown Prosecutor, as head of a Special Crown Prosecutors Department to deal with strike cases. Graham was livid, but eventually worked out a deal with Phillips to split cases between them. Though he felt the strike was less serious than it was made out to be, he was still on the side of constituted authority. It was Graham that convinced Alderman Sparling and the Police Commission that it was paramount the police sign a loyalty pledge if they were to remain on duty. When this backfired and the vast majority of police refused to sign the pledge, Sparling attempted to blame Graham. Later, Graham said of Sparling, “if his courage and brains had equaled his vanity, he would have been an exceedingly valuable man during the strike” (Kramer and Mitchell 2010, 111).

Graham was also frustrated by the Citizens’ Committee’s attempts to undermine his authority. Early during the strike, the Citizens attempted to convince Graham to prosecute the strike’s leadership, but Graham was unimpressed by their imposition and made it clear that he “was still Crown prosecutor and would decide how the cases would be handled” (Kramer and Mitchel 2010, 81). To side-step Graham, the Citizens went instead to Hugh Phillips, who was happy to work with them. Over time, Graham’s resistance to the Citizens’ machinations waned. While he never actually gave in to their demands, he eventually stopped trying to fight them. Graham was at the meeting that determined which strike leaders would be arrested on June 17, but he did and said little. He was unconvinced charges of sedition would stick, but did nothing to stop the arrests. Later during the sedition trials, Graham was asked what level of government authorized the arrests, to which he responded that he didn’t know. When he was asked outright whether he had authorized them, he simply said “no” (Kramer and Mitchell 210, 164).

Graham went on to have a successful law career after the strike. In 1929, he became a judge, replacing Hugh John MacDonald. He was President of the Law Society of Manitoba from 1935 to 1937 and, after retiring in 1944, became a counsel to the Winnipeg Board of Police Commissioners. Graham Died in Winnipeg on June 12, 1951.

Judges

Alexander Casimir Galt (1853-1936)

Alexander Casimir Galt was born in Toronto on March 15, 1853. He was educated at several different schools, including The University of Toronto and Osgoode Hall, and was called to the Ontario Bar in 1876. Galt practiced law in Toronto (1876 to 1896) and Rossland, BC (1896-1906) before coming to Manitoba in 1906, partnering at the firm Tupper, Galt, Tupper, Minty, and McTavish. He was appointed King’s Council in 1909 and appointed to the Court of King’s Bench in 1912. Several accounts of Galt depict him as being poorly regarded in his profession. His old firm was elated when he was appointed to the Court of King’s Bench, as they saw it as the only way to get rid of him (Larsen 2017, 68). He was considered a stickler for details to the point of absurdity: he once made a lawyer draft and repeatedly redraft a court order, revealing, only when the lawyer finally demanded to know, that the document’s only issue was that it contained a split infinitive (Ibid).

Galt acted as judge for the trial of Fred Dixon, who was arrested for editing the Western Labor News after William Ivens and J.S. Woodsworth’s arrests. Dixon’s trial began on January 20, 1920, during which he had to contend with Galt’s open presumption of his guilt. Galt spoke to the jury directly, stating that the evidence against Dixon was indefensible and that he was part of “one of the most infamous conspiracies I have ever heard of in Canada” (Larsen 207, 70). Galt went on to accuse Dixon of being as guilty of sedition as William Ivens, George Armstrong, and R.B. Russell, two of whom had not yet been found guilty of sedition – their trial was being conducted in a room down the hall (ibid, 71). Despite this, Dixon was acquitted, but before leaving the courtroom, Galt accused him one last time of fomenting an “absolutely illegal and unjustifiable strike” (ibid).

Galt retired in 1933 and passed away in 1936.

Thomas Graham Mathers (1859-1927)

Thomas Graham Mathers was born in Lucknow, Ontario on April 16, 1859. He began to study law in 1884 and was called to the Manitoba Bar in 1890, after which he worked in law firms such as Munroe, West, and Mathers from 1890 to 1895, Mathers and Anderson from 1895-1897, and with Chief Justice Hector Mansfield Howell from 1898-1905. Mathers took an active role in municipal politics: he was elected alderman from 1898 to 1899, served as the Chair of the Board of License Commissioners from 1899 to 1900, and was a member of the founding Advisory Board of the Winnipeg Foundation in 1921. In 1905, Mathers was appointed to the Court of King’s Bench and in 1910, he was appointed Chief Justice.

Labour unrest existed long before the start of the Winnipeg General Strike. The relationship between employer and employee had been tense and, sometimes, outright hostile for some time, especially after the start of the First World War. In response to this, the Government of Canada launched several investigatory commissions to examine this tense atmosphere, two of which were chaired by Mathers. Mathers was no stranger to chairing commissions – he had chaired a hospital commission in 1908, a police station commission in 1914, and the Royal Commission to Inquire into Construction of Manitoba Parliament Buildings in 1915. When hostility between the metal trades and their employers began to heat up following the formation of the Metal Trades Council in 1918, Mathers was called on again to chair the Royal Commission to inquire into Metal Trades in Winnipeg. The commission began on June 26, 1918, and its final report was submitted on August 2. Its conclusion attribution the main cause of the dispute to be employers’ refusal to recognize the Metal Trades Council, but it was also critical of some of the Council’s tactics. This caused both sides to reject the report.

Despite this, Mathers was called on again on March 22, 1919, to chair the Royal Commission to inquire into Industrial Relations between employers and employed in Canada, which analyzed labour relations more generally. Again, however, neither side was placated. The Winnipeg Trades and Labor Council believed the government to be complicit in their struggles and arranged boycotts of the hearings, while many employers found the commissions to be too lenient towards labour (Bumsted 1994, 104). Mathers’ final report was submitted on June 13, 1919, during some of the most volatile days of the General Strike. It concluded that poor wages and working conditions and lack of union recognition, rather than any socialist or foreign influence, were the primary causes of these disputes, and recommended labour reforms such as legislating a minimum wage, an eight hour work days, and collective bargaining. After the strike leaders were arrested on June 17, Mathers granted them bail, but refused to do so for the “enemy aliens” arrested alongside them, claiming that he only had authority over criminal cases.

Mathers passed away in Rochester, Minnesota on August 16, 1927.

Thomas Llewellyn Metcalfe (1870-1922)

Thomas Llewellyn Metcalfe was born in St. Thomas, Ontario on February 21, 1870, but came to Manitoba shortly thereafter, attending public School in Portage La Prairie. He was called to the Manitoba Bar in 1894 and practiced law at the firm Metcalfe, Sharpe, Stacpoole, and Elliott. Into the 20th century, Metcalfe began to rise in prominence, becoming a commissioner to revise Dominion Statutes in 1906, a member of the Dominion Fisheries Commission in 1909, a member of the Court of King’s Bench that same year, and a leading member of the Liberal party. Despite his career successes, Metcalfe was seen by some as lacking in moral character and self-control, being described as “one of the province’s least dignified judges” (Larsen 2017, 52). This had the potential to be especially awkward, as Metcalfe was alleged to have been having an affair with the wife of prosecutor and Citizens’ Committee member A.J. Andrews, whom he had once had a physical altercation with after Andrews found the two of them in bed (Kramer and Mitchell 2010, 306).

Despite also being described as a kind and likable person who often felt sympathy for the accused, he showed little affection towards the arrested leaders of the General Strike, whose trials he presided over. During the trial of R.B. Russell, Metcalfe was operating under the assumption that the strike itself was indisputably illegal. He refused to allow Russell to describe his past work or any attempts he made to settle the strike, and when the defence claimed that simply being in favour of a general strike was not a crime, Metcalfe responded, “I think it is” (Larsen 2017, 55). He further frustrated the defence by overruling every attempt it took to make its case, claiming any attempt to explain the origins of the strike or expose the Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand were irrelevant. Metcalfe frustrated Russell’s lawyer, Robert Cassidy, so much that he abruptly closed his case without calling all of his planned witnesses, citing the inability of him and Metcalfe to agree with on constituted as evidence (Norm Larsen 2017, 56). At the end of the trial, Metcalfe addressed the jury for four hours and outright stated that if he was a member of the jury, he would find Russell guilty.

The trial of the “Winnipeg Seven” proceeded in a manner similar to Russell’s. Almost as it began, an argument broke out between Metcalfe and defence lawyer E.J. McMurry about the jury selection process. The argument became so heated that McMurry walked out of the courtroom and didn’t return until the following day, demanding Metcalfe treat him with more respect. A.A. Heaps, who was representing himself, also expressed concerns about jury selection. Metcalfe admonished that he was lucky he wasn’t being tried back in the days when guilt was determined by whether one floated or drowned, to which Heaps retorted, “I think we’d stand more of a chance that way” (Notable Trials 78). Several more screaming matches took place between Metcalfe and the defence throughout the trial, to the point that Metcalfe complained he was “sick and tired” of hearing about the trial’s fairness (Norm Larsen 2017, 80). During the final addresses to the jury, Metcalfe frequently interrupted the defence. Walter Truemen, counsel to A.A. Heaps and John Queen, became so frustrated that he quit mid-address, claiming that he could no longer continue with Metcalfe as judge and leaving Heaps and Queen to represent themselves. In the end, Metcalfe gave the jury the same instructions he gave the jury during Russell’s trial. After guilty verdicts were returned for all except Heaps, Metcalfed cited the jury’s call for mercy as the only reason he didn’t mete out the maximum sentence, as he did for Russell.

The trials took a physical toll on Metcalfe. He was unwell by the end of Russell’s trial and the trial that succeeded it only exacerbated this. Though he was elevated to a position in the court of appeal on October 6, 1921, he died less than a year later, on April 2, 1922. According to Mary Jordan, Russell’s assistant, Metcalfe attempted to contact Russell near the end of his life, presumably to reconcile, but Russell refused, “let him die with his guilty conscience”, a decision he later regretted (Larsen 2017, 64)

Robert Moore Noble (1869-1934)

Robert Moore Noble was born in Ontario, near Uxbridge, on August 18, 1869, eventually leaving for Toronto to article and enroll in Osgoode Hall. He was called to the Ontario bar in 1892 and practiced law for several years in Ontario before being called to the Manitoba Bar on June 29, 1904, and settling in Carberry. He was a partner in various firms – including that of future Citizens’ Committee member A.J. Andrews – before becoming a Provincial Police Magistrate in 1916. He helped found the First Presbyterian Church and served on its board, was a member of the Caledonian Club, and a Free Mason from the Ancient Landmark Lodge.

During the strike and its aftermath, Noble presided over both the preliminary hearing of the arrested British strike leaders and the immigration hearings of the “enemy aliens” who were arrested alongside them. In both cases, Noble showed little sympathy for the defendants. He allowed the violence of Bloody Saturday to be admitted as evidence against the British strike leaders, despite the fact that they were in prison at the time of its organization, claiming “they started the fire” (Kramer and Mitchell 2010, 241). He consistently ruled against the defense’s objections and in favour of those made by the prosecution, and dismissed the defense’s claim that the prosecution – consisting of Citizens’ Committee members A.J. Andrews and James Coyne – were in a conflict of interest, given their role during the strike. Noble was equally biased against the defense in the immigration hearings, where he constantly overruled the defense and had a loose understanding of the recently amended Immigration Act (Kramer and Mitchell 2010, 218).

After the strike, Noble served in his position until April 25, 1934. He died not long after, on May 16, 1934).

Hugh Amos Robson (1871-1945)

Hugh Amos Robson was born at Barrow-in-Furness, England, on September 9, 1871, and came to Canada in 1882. He studied law in Regina (then part of the Northwest Territories) and personally witnessed the trial of Louis Riel in 1885. He was called to the territorial bar not long after and moved to Winnipeg in 1899 to practice law in the firm of James Aikins. In 1909, he was made King’s Counsel and was appointment to the Court of King’s Bench. He later resigned his position to chair the provincial public utilities commission that introduced public hydroelectricity from 1911-1914.

On July 4, 1919, Hugh Amos Robson was appointed to head the “Royal Commission to enquire into the report upon the causes and effects of the General Strike which recently existed in the City of Winnipeg for a period of six weeks, including the methods of calling and carrying on such a strike”, more commonly referred to simply as the “Robson Commission”. This commission was tasked with investigating the causes of the strike and to determine whether or not it was seditious in intent. This was one of the few concessions the Strike Committee received for agreeing to call off the strike. Hearings were held throughout the next few months and statements were taken from several parties, including T.J. Murray, who represented the arrested strike leaders, Jules Preudhomme, who represented the City of Winnipeg, and W.J. Moran, who represented Manitoba Bridge and Iron Work. The Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand sent no one, but did submit a statement. One of the most significant statements came from James Winnipeg, President of the Winnipeg Trades and Labor Council and a member of the Strike Committee’s executive, who pointed to the high cost of living, poor wages, poor working conditions, and a lack of job security as the primary causes of the strike. Although Robson’s final report fell in line with the popular belief that socialism was a dangerous, mostly foreign ideology that had wormed its way into labour circles, he drew a distinction between it and the strike as a whole, and agreed with Winning’s assessment of strikers’ motives and reasoning, quoting his statement at length.

After the conclusion of his commission, Robson served as a Bencher for the Law Society of Manitoba until 1925, co-authored several law texts, and was elected leader of the provincial Liberals in 1927, which he held until 1930 when he was appointed to the Court of Appeal. He served there until 1943 and became Chief Justice of Manitoba from 1944 until his death on July 9, 1945. He held an honourary doctorate from the University of Manitoba and its Robson Hall bears his name.

Federal Government

At the time of the Winnipeg General Strike, the Federal Government was under the leadership of Prime Minister Borden’s Conservative-Union government. While the strike was arguably a matter for the City and Provincial Governments to deal with, when Federal postal workers went on strike, the Federal Government did intervene, giving their employees an ultimatum to return to work or lose their employment. Furthermore, the strike increasingly came under Federal jurisdiction as members of the Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand, particularly A.J. Andrews, found that they could more easily direct the outcome of the strike through Federal representatives Arthur Meighen and Gideon Robertson. In the aftermath of the Strike, Borden’s government lost some support from those who supported the labour movement due to their role in ending the strike.

Arthur Meighen (1874-1960)

Arthur Meighen was born in Ontario in 1874 to Joseph Meighen and Mary Jane Bell. After obtaining a Bachelor with honours in mathematics from the University of Toronto in 1896, Meighen taught math and other subjects in Ontario, before moving to Manitoba in 1900. Meighen initially settled in Winnipeg to article but two years later, he began working in Portage la Prairie, where he would establish his own practice in 1903 once he was called to the bar. By 1908, Meighen had entered the realm of politics, running as a Conservative representative in the Federal election and winning his seat to join the Opposition. In the 1911 Federal elections, Robert Borden was successful in leading his party into power. Meighen made an impression on Borden prior to and after his victory, and as a result, in 1913, Meighen was appointed Solicitor General for the Cabinet. In 1917, he became Secretary of State and later that year, Minister of the Interior.

It was his appointment in 1919 as Acting Minister of Justice that tied Meighen to the Winnipeg General Strike. As the Strike occurred not long after the end of the First World War, Prime Minister Borden and Dominion Minister of Justice Charles Doherty, had spent most of their time since January of 1919 at the Paris Peace Conference, negotiating the peace terms for the war. Consequently, in their absence, business related to the Winnipeg General Strike was delegated to Meighen and Minister of Labour Gideon Robertson.

From the beginning of the conflict, Meighen could not be described as a neutral mediator. He was already acquainted with A.J. Andrews and Isaac Pitblado, which gave the Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand an opportunity. Meighen did not know at that time, how much control Andrews would have over the strike based on this relationship. Andrews frequently sought out Meighen to ensure a favourable outcome for the Citizens. Through meetings and correspondence, Andrews provided Meighen with updates on the strike, told from his perspective, and further, upon hearing that Meighen was on his way to Winnipeg with Minister Robertson, gathered a group of Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand members and traveled to Fort William to ensure he had control of the strike narrative, spinning it as a Bolshevik revolution.

With a close working relationship, Andrews was also a clear choice for Meighen when the latter sought to appoint a local representative in Winnipeg for the Federal Justice Department. In this role, Andrews was advised to keep an eye out for potential evidence of seditious activities and advise Manitoba’s Attorney General on relevant matters. This proved to be a mistake as Andrews continuously disregarded one important fact: he had no official authority in the matter, beyond advising the Federal Government and the Attorney General.

Andrews further influenced Meighen when it came to amending the Immigration Act to ensure that those born outside of Canada be deported if they were accused of sedition. However, in Andrews’ opinion, the act did not go far enough, as it did not allow for the deportation of those who were born in the Commonwealth and who had lived in Canada for three years. Under this rule, very few strike leaders could be deported and as a result, Andrews led Meighen to believe he would arrest strike leaders under the Immigration Act, and, once given permission, arrested those that could not be deported under the Criminal Code instead, to Meighen’s surprise. Another surprise came when the Federal Government received a hefty bill for the prosecutions of the strike leaders. Though Andrews had told Meighen on many occasions that other lawyers were offering support, he always implied they were doing so free of charge.

Though Meighen was essentially used and manipulated by the Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand, in the strike’s aftermath, his political career advanced. The following year, a few short months after the strike trials had ended, Meighen succeeded Borden as Prime Minister of Canada. He held the position until 1921. He further held the position of Prime Minister briefly in 1926, until he lost a no confidence motion that same year. In the years that followed, he worked in law, at the firm of Maxwell, Meighen & Associates Ltd., and returned to politics in later years as both a senator and, once more, the leader of the Conservative party. Meighen died on August 5, 1960 and is buried in Ontario.

See also: Who: Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand for information on the Committee and A.J. Andrews.

Gideon Decker Robertson (1874-1933)

Gideon Decker Robertson was born on August 26, 1874 in Welland, Ontario. From 1893 to 1908, Robertson worked for the Canadian Pacific Railway as a telegrapher. In 1908, he was elected general chairman of the Order of Telegraphers and rose to the rank of deputy president and vice-president in 1914 and 1915 respectively. In 1917, under the advice of Arthur Meighen, Prime Minister Robert Borden appointed Robertson to the Senate, as he sought someone with a background in labour and union relations to help his government gain their support. Additionally, Robertson was a moderate and far from a labour radical. For this reason, Robertson could help mediate labour disputes while keeping the government’s best interests in mind. Shortly after being appointed Senator, Robertson was also appointed as a minister without a portfolio in Borden’s cabinet.

In 1918, Robertson helped to mediate several strikes. Alongside Federal representative Mr. Campbell, Robertson was in Winnipeg to help mediate the civic employees strike in 1918, and found himself disagreeing with city officials such as Mayor Gray and Aldermen Fowler, as Robertson believed firemen should be brought back to work without having to sign a no-strike contract. Robertson was able to help reach an agreement whereby the firefighters, excluding their officers, were given the right to unionize. Later that year, after two employees were dismissed from Great-Northwestern Telegraph, employees of the company across Canada protested the dismissals by striking. Robertson informed the company that if the two fired employees were not rehired, the Federal Government, which owned the company, would step in and take control. The resolution was quick: the strike in Toronto was reported to be one of the shortest strikes recorded, ending in 20 minutes (Winnipeg Tribune, July 16, 1918). Later that year, Robertson stepped in to prevent a strike of freight handlers in Calgary from going national. The Federal Government responded by prohibiting wartime strikes “in industries covered by the Industrial Disputes Investigation Act.” (Kramer and Mitchell 2010, 21). In response, William Ivens, a future leader of the Winnipeg General Strike, proposed a national general strike in support of the freight handlers. The Women’s Labor League were also reported as having “verbally attacked the girl clerks who had temporarily relinquished their regular duties to handle the work of the freight shed department” (Winnipeg Tribune, October 14, 1918). On October 21, a strike vote by street railway workers, printers, culinary workers, and police in Winnipeg was taken to determine whether fifty unions representing over 20,000 employees were prepared to walk out on October 24 if the Federal Government did not withdraw its “no-strike” order-in-council (Winnipeg Tribune, October 21, 1918). A strike committee was appointed in preparation, which included two representatives from each union. Robertson was able to reach an agreement with the strikers on October 22, preventing a general strike. Shortly after the resolution of the freight handlers strike, Robertson was appointed Minister of Labour.

When the Winnipeg General Strike began in Winnipeg the following spring, it quickly became a Federal issue when postal workers joined in. On his way to Winnipeg with Acting Minister of Justice Arthur Meighen, Robertson was intercepted in Fort William (now Thunder Bay) by the Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand, who convinced Robertson and Meighen of their take on the strike. Though Robertson came from a labour background, he had no tolerance for what he saw as an attempt to overthrow the constituted authority of the Federal Government. While he believed in collective bargaining and the right to unionize, this right, in his opinion, was only reserved for small craft unions, not for an organization as all encompassing as the One Big Union. More importantly, Robertson understood that a victory for the strikers in Winnipeg would mean a victory for the OBU, resulting in potentially more strikes across Canada.

Once in Winnipeg, Robertson spent most of his time speaking to the Citizens’ Committee and Provincial authorities, neglecting the Strike Committee and seldom conferring with municipal representatives such as Mayor Gray. Throughout the mediations, Robertson came close to a resolution between the Iron Masters and the railway unions. However, the agreement would not recognize the Metal Trades Council as a bargaining agent and, consequently, it was rejected by the Strike Committee (Kramer and Mitchell 2010, 162). As the strike went on, Robertson assisted in arresting the strike leaders. When arrest warrants were being drafted, Robertson received a call from Provincial authorities asking him to hold the arrests, as they had reason to believe a settlement was soon to be reached. Robertson hesitated to move on the arrests based on this information but was convinced by the Citizens’ Committee, particularly Travers Sweatman, to move forward. Following this decision, he accompanied A.J. Andrews to Stony Mountain Penitentiary to secure space for the soon to be arrested leaders, as they believed that the Vaughan Street Gaol was too accessible to the public, which they believed could lead to a riot. Regardless, a protest was planned for June 21. In the hours before Bloody Saturday, Robertson, alongside Mayor Gray, met with strikers to try and prevent the parade. Robertson further offered to speak to strikers and strike sympathizers in Victoria Park if the parade was called off, but the violence that erupted that day made the offer moot. On June 23, following a statement from the Federal Government that it would no longer negotiate or attempt to reach a settlement until the sympathy strike was called off, Senator Robertson left Winnipeg. A few days later, the strike was called off, ending on June 26.

Following the strike, the Federal Government lost some of the support they had hoped to gain from labour when Robertson was first appointed in 1917. Robertson continued as Minister of Labour when Arthur Meighen became Prime Minister in 1920, until the Conservative Party lost the 1921 election. In 1930, Robertson resumed his role as Minister of Labour under the government of Prime Minister R.B. Bennett. He was forced to resign in 1932 due to ill-health, having suffered a stroke in Geneva. On August 3, 1933, Robertson suffered another stroke and was unable to recover. He died a few weeks later, on August 25

See also: Who: Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand for information on the Committee.