Where

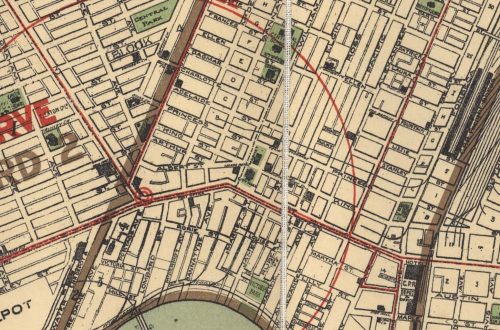

In 1919, the City of Winnipeg was not the City of Winnipeg it is today. Prior to 1972, regions such as St. Boniface, Fort Garry, and St. James were their own municipalities, each with their own City Councils and administrative systems, though there was some overlap. All of Greater Winnipeg and the locations showcased below are in Treaty One territory, the lands of the Anishinaabeg, Cree, Oji-Cree, Dakota and Dené peoples, and on the homeland of the Métis Nation. It is important to acknowledge that all aspects of the General Strike took place on stolen lands whose rightful occupants were removed by force and without consent.

Geography served as a key place of contention during the strike. Various places within Winnipeg became associated with the different “sides” of the conflict. These associations factored heavily into the narratives and propaganda about the strike and those involved. These narratives shaped people’s views and opinions and, as such, understanding place is crucial to understanding the strike itself.

Previous

Next

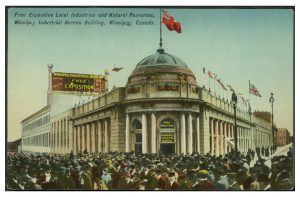

Board of Trade/Industrial Bureau

In 1911, the Industrial Bureau Exposition Building was constructed on land formerly occupied by the Manitoba Hotel. The construction experienced some delays due to a dispute between the Plasters’ Union and the Builders’ Exchange over the latter hiring carpenters to do plastering work for half the price. The Industrial Bureau was an organization that collected and distributed statistics and information on Winnipeg business. The new building at 269 Main Street at Water Street (now William Stephenson Way), would offer space to various tenants, including the Winnipeg Board of Trade, incorporated in 1879 under its first president, A.G.B. Bannatyne. Its new premises in the Industrial Bureau building were further utilized as a location for patriotic gatherings during the war and consequently, its grounds were suggested as a possible space for a war memorial following the First World War.

Starting in May of 1919, the building acted in part as the headquarters of the Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand, who occupied the building and held meetings at all hours of the day throughout the strike. Headquarters were advertised to readers of the Winnipeg Citizen, who were informed that offices, such as the Citizens’ Employment Information Bureau, could be found in the Board of Trade Building. In the midst of the strike, a sign briefly went up on June 2, 1919, more publicly marking the building as the headquarters of the Committee. It was taken down that same day in protest by veterans marching towards St. Boniface on their way back from a meeting with Premier Norris at the Legislative Building.

In June, the Committee also held daily prayer meetings in the building with the aim of ending the strike. However, from the perspective of Western Labor News, “When the doctor says there is no hope, the priest is sent for… It will now be in order for the committee of 1,000 to confess its sins, pray for mercy, and pass away.” (Western Labor News, June 4, 1919). Based on the outcome of the strike, this perspective did not hold true.

Throughout the strike, there was much debate between the Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand and the strikers on whether the Board of Trade was synonymous with the Citizens’ Committee. No conclusive evidence corroborating or disproving these claims was ever presented. While the building often hosted the anti-labour Citizens’ Committee, following the strike, the building did open its doors to pro-labour events and speakers. Its auditorium held a gathering in July 1919, led by strike leader Fred Dixon to discuss the ongoing immigration hearings of some of the arrested strikers. The Board of Trade also invited pro-labour speakers – Alderman Robinson and H. G. Veitch of the Trades and Labor Council.

Immediately following the Strike, in July of 1919, the Winnipeg Board of Trade amalgamated with the Winnipeg Industrial Bureau. The newly merged organization inherited the Board of Trade name, and amended the latter organization’s charter and bylaws. The new Winnipeg Board of Trade was described as “the largest and most representative body of its kind in the Dominion of Canada.” (Winnipeg Tribune, April 3, 1920) and continued to act as a meeting space for all Winnipeggers, hosting approximately 1,500 meetings per year.

Click here to see former location on map.

Image Source: Martin Berman Postcard Collection. COWA (vol. 1C)

See also: Who: Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand

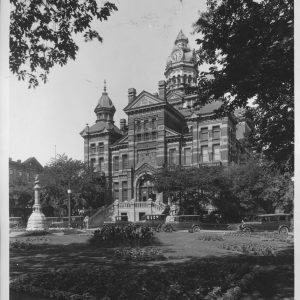

Winnipeg’s City Hall in 1919, located on the West side of Main Street between Market and William Avenues, was the second of three City Halls that have stood in Winnipeg. The first was built in 1875, but was plagued with structural problems and required significant work just to keep the building standing. It was demolished in 1883 and a new one – often called the “Gingerbread House” due to its distinctive look – was erected in 1886. However, this City Hall soon became inadequate, as Winnipeg’s population grew from about 20,000 when the Gingerbread House was built to about 136,000 in 1911. It also didn’t serve aesthetically, as the City began to embrace the “City Beautiful” movement. A City Planning Commission recommended the construction of a new City Hall in 1913. A contest was held and a new design was chosen, but due to the 1913 recession and the outbreak of the First World War, the new building was never built.

Winnipeg’s City Hall in 1919, located on the West side of Main Street between Market and William Avenues, was the second of three City Halls that have stood in Winnipeg. The first was built in 1875, but was plagued with structural problems and required significant work just to keep the building standing. It was demolished in 1883 and a new one – often called the “Gingerbread House” due to its distinctive look – was erected in 1886. However, this City Hall soon became inadequate, as Winnipeg’s population grew from about 20,000 when the Gingerbread House was built to about 136,000 in 1911. It also didn’t serve aesthetically, as the City began to embrace the “City Beautiful” movement. A City Planning Commission recommended the construction of a new City Hall in 1913. A contest was held and a new design was chosen, but due to the 1913 recession and the outbreak of the First World War, the new building was never built.

As the centre of Civic Government, City Hall played an important role during the General Strike as a meeting place for settlement negotiations. In addition to regularly scheduled Council sessions, many special and informal meetings of Council took place here, as Mayor Gray attempted to broach a settlement between the strikers and their employers. Representatives such as R.B. Russell and James Winning of the Strike Committee and A.J. Andrews, Isaac Pitblado, A.L. Crossin, and Travers Sweatman of the Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand were at City Hall frequently. As well, strike leaders John Queen, A.A. Heaps, and E. Robinson conducted their work as Aldermen out of City Hall.

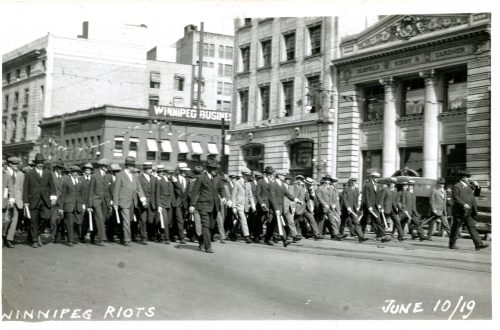

City Hall was also a popular place to hold protests and rallies, both for and against the strike. Demonstrations were held outside City Hall on several occasions, particularly by returned soldiers. On May 31, 10,000 pro-strike returned soldiers marched to City Hall while Council was still in session, demanding the City rescind the ultimatum it had issued to the police to sign the Slave Pact or be fired. Council was suspended and Mayor Gray came out to meet the soldiers, but he was non-committal and the soldiers booed him. On June 4, anti-strike veterans held their own demonstration at City Hall in support of “constituted authority” and against “enemy aliens” (Idiong 1997, MHS). Several other marches and demonstrations took place at City Hall throughout the strike.

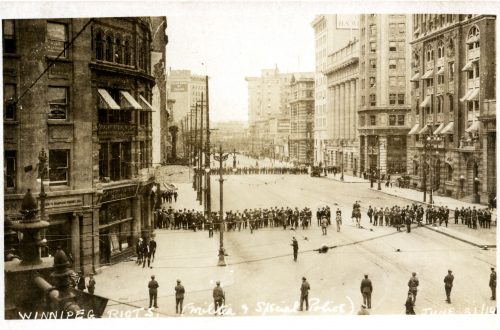

City Hall was also the scene of Bloody Saturday. People had gathered in front of City Hall for the silent parade the pro-strike soldiers had planned. As a streetcar operated by strikebreakers approached, the incensed crowd attempted to derail it. The Royal Northwest Mounted Police were on the scene and charged into the crowd on William Avenue after Gray read the Riot Act. They rode around Market Square and back to Main Street, where they shot and killed Mike Sokolowski. During the violence, City Hall became a triage centre, as many of the injured were brought to Mayor Gray’s office to have their wounds treated by Dr. J.H. Leeming, the City’s bacteriologist.

After the strike, the pre-war plan for a new City Hall was never acted on and the building began to decay. The tower had to be removed in 1961 as it had started to crumble – falling plaster nearly hit a passersby in 1958 (City of Winnipeg). It was finally demolished in 1962 to make way for the current Civic Centre, in which a model of the Gingerbread House is still on display.

Click here to see former location on map.

Image Source: Anti-strike veterans parading at City Hall holding signs against Bolshevism and “enemy aliens”. L.B. Foote fonds. AM.

See also: Who: Government and Politicians

![Crescent Creamery Sherburn plant. COWA. Committee on Public Health and Welfare (A587 File 2133[1]). Crescent Creamery Sherburn plant. COWA. Committee on Public Health and Welfare (A587 File 2133[1]).](http://1919strike.lib.umanitoba.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/F0001_0001_0002_A0587_2133-1_003-188x300.jpg) Crescent Creamery was a local business in Winnipeg, producing milk, cream, butter, buttermilk and ice cream. First opened in 1904 on Lombard Street, the business quickly expanded, opening an ice cream and ice-making plant on Burnell Street in 1911. By 1913, the creamery was selling over 1,500,000 pounds of butter in Winnipeg, and based on the growing demand, they planned to open a dairy plant at their Burnell location. However, in 1914, they bought out their competitor – Carson’s Hygienic Dairy Company, which already had a plant on Sherburn, prompting Crescent Creamery to open its new dairy plant at the former Carson facility in May of 1914, rather than building a new facility at Burnell Street. During the Strike, Crescent Creamery operated under General Manager and Director James Malcolm Carruthers, the co-founder of the creamery, alongside Robert Arthur Rogers. Carruthers was credited for coming up with the idea to place placards on milk delivery trucks authorizing the deliveries by permission of the Strike Committee.

Crescent Creamery was a local business in Winnipeg, producing milk, cream, butter, buttermilk and ice cream. First opened in 1904 on Lombard Street, the business quickly expanded, opening an ice cream and ice-making plant on Burnell Street in 1911. By 1913, the creamery was selling over 1,500,000 pounds of butter in Winnipeg, and based on the growing demand, they planned to open a dairy plant at their Burnell location. However, in 1914, they bought out their competitor – Carson’s Hygienic Dairy Company, which already had a plant on Sherburn, prompting Crescent Creamery to open its new dairy plant at the former Carson facility in May of 1914, rather than building a new facility at Burnell Street. During the Strike, Crescent Creamery operated under General Manager and Director James Malcolm Carruthers, the co-founder of the creamery, alongside Robert Arthur Rogers. Carruthers was credited for coming up with the idea to place placards on milk delivery trucks authorizing the deliveries by permission of the Strike Committee.

When the Strike Committee called creamery workers to walk off the job on June 4, Crescent Creamery was one of two dairy companies that provided milk to the Special Food Committee that City Council had created. On June 9, 1919, Crescent Creamery printed an advertisement in the Tribune, reminding its milk drivers that they were under an agreement not to walk out on sympathetic strike. All employees were called to return to work by 3 pm on June 10, after which time, any employees still unaccounted for would be replaced, with hiring priority given to returned soldiers. On June 17, ten men were arrested near Crescent Creamery for intimidation. The incident was reported in various media sources, included Western Labor News, which stated that the men were simply standing on Portage Avenue, near the premises of Crescent Creamery, when a police car pulled up. Officers with revolvers and bludgeons promptly arrested the men (Western Labor News, June 18, 1919). The Winnipeg Tribune, on the other hand, stated that the men were former employees of Crescent Creamery, picketing near the business and threatening current employees, with one picketer warning a driver not to come into work the following day, as his delivery truck would most likely be “smashed up” (Winnipeg Tribune, June 17, 1919).

Following the strike, Crescent Creamery’s Sherburn location was bought out by the Crescent Pure Milk Company on December 31, 1919. Crescent Creamery still manufactured ice cream at this time, but this location became Hignell Printing in the early 1940s. Over the years, it was sold to many businesses, including Modern Dairies, Beatrice Foods, and finally Parmalat.

Click here to see former Burnell location on map.

Click here to see former Sherburn location on map.

Image Source: Crescent Creamery Sherburn plant. COWA. Committee on Public Health and Welfare (A587 File 2133[1]).

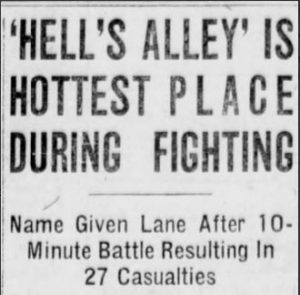

On June 21, 1919, an unassuming alley between James and Market Avenues quickly became an escape route for many strikers when shots rang out on Main Street. Special Police followed suit, trapping the fleeing crowd. A skirmish broke out in what would shortly be known as Hell’s Alley. Bricks were thrown by the crowd, batons were used by the Special Police.

The fight went on only for approximately 10 minutes, but at the end of it, the Special Police, who had later claimed that the event “had trench action in France beaten” (Winnipeg Tribune, June 23, 1919) had renamed the alley accordingly. Very little about this event is known, other than what was reported by the Winnipeg Tribune, which was known to have an anti-strike bias. Today, what used to be Hell’s Alley is covered by the Centennial Concert Hall.

Click here to see former location on map.

Image Source: Winnipeg Tribune, June 23, 1919. UML.

See also: When: June 21, 1919

The Labor Café – Strathcona and Oxford Hotels

The Strathcona and Oxford Hotels were notable as the locations of the Labor Café organized by Helen Armstrong, the Women’s Labor League, and its Relief Committee. Built in 1905, the six-story Strathcona Hotel was located at Rupert Avenue and Main Street, and was the first location of the Labor Café, which occupied the hotel’s kitchen and 1,600 square foot dining area. The café provided free meals to women and assisted them with rent. Men were also fed, but they were required to pay unless they were too poor to afford it, in which case a ticket obtained from the Relief Committee secured them a meal. The Labor Café was able to operate in the Strathcona for 10 days free of charge before moving to the Oxford Hotel. The Western Labor News was somewhat ambiguous as to whether the hotel’s proprietor had evicted them (Western Labor News, June 17, 1919). After the strike, ownership of the Strathcona changed hands several times before it was renamed the “Cornwall Hotel in 1932. It was finally demolished in 1967 as part of the construction of the Manitoba Museum.

The Strathcona and Oxford Hotels were notable as the locations of the Labor Café organized by Helen Armstrong, the Women’s Labor League, and its Relief Committee. Built in 1905, the six-story Strathcona Hotel was located at Rupert Avenue and Main Street, and was the first location of the Labor Café, which occupied the hotel’s kitchen and 1,600 square foot dining area. The café provided free meals to women and assisted them with rent. Men were also fed, but they were required to pay unless they were too poor to afford it, in which case a ticket obtained from the Relief Committee secured them a meal. The Labor Café was able to operate in the Strathcona for 10 days free of charge before moving to the Oxford Hotel. The Western Labor News was somewhat ambiguous as to whether the hotel’s proprietor had evicted them (Western Labor News, June 17, 1919). After the strike, ownership of the Strathcona changed hands several times before it was renamed the “Cornwall Hotel in 1932. It was finally demolished in 1967 as part of the construction of the Manitoba Museum.

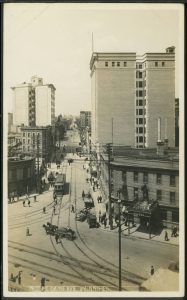

The Labor Café was reopened in the Oxford Hotel, where it made use of an even larger kitchen to serve between 1,200 and 1,500 meals a day. Located on Notre Dame Avenue at Albert Street, the Oxford Hotel was built in 1905 and sold to James Richardson in 1923. Though no longer the Oxford Hotel, the building still stands with “Oxford Hotel” written on one of the awnings.

Click here to see former Strathcona Hotel location on map.

Click here to see former Oxford Hotel location on map.

Image Source: Notre Dame avenue, showing Oxford Hotel on left. COWA. Martin Berman Postcard Collection (vol. 4D).

See also: Who: Women

Labour temples in Winnipeg served as meeting spaces for unions and provided services to the working class. Many temples served particular communities or ethnicities, such as the Ukrainian Labor Temple (591 Pritchard Avenue) built in 1918, and the Liberty Temple (410 Pritchard Avenue) built in September 1917, which served the Jewish community. Outside of these and other labour temples, some unions with more limited means would rent space as needed from Orange Hall on Princess Street for various labour and social functions.

Labour temples in Winnipeg served as meeting spaces for unions and provided services to the working class. Many temples served particular communities or ethnicities, such as the Ukrainian Labor Temple (591 Pritchard Avenue) built in 1918, and the Liberty Temple (410 Pritchard Avenue) built in September 1917, which served the Jewish community. Outside of these and other labour temples, some unions with more limited means would rent space as needed from Orange Hall on Princess Street for various labour and social functions.

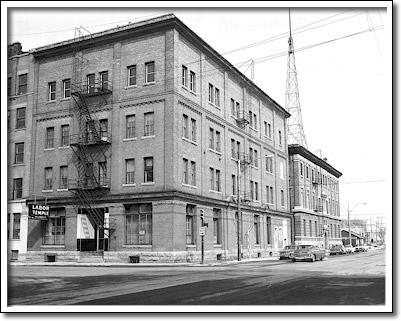

Built in 1906, the James Street Labor Temple was officially known as Trades Hall until 1913. While Winnipeg labour temples were generally pro-labour and consequently, pro-strike, the James Street Labor Temple (165 James Avenue) in particular, where the Winnipeg Trades and Labor Council offices were located, acted as the headquarters of the strikers and those sympathetic to their cause. Votes in favour or against a potential strike took place in this building, as did daily meetings and council sessions throughout the strike. The James Street Labor Temple held the elections for various strike committees. From this location, the Western Labor News was printed, as were posters and placards permitting the continuance of essential services during the strike.

As hubs of labour rights throughout Winnipeg, labour temples also became targets for authorities and those opposed to the strike, particularly media sources such as the Winnipeg Citizen and the Winnipeg Telegram, who sometimes referred to the James Street Labor Temple as the James Street Soviet. In the early hours of June 17, search warrants allowed for many labour temples, mainly the James Street Labor Temple, the Ukrainian Labor Temple, and Liberty Temple, to be raided by police searching for seditious literature. These raids would later assist the prosecution in convicting the arrested strike leaders.

Today, only the Ukrainian Labor Temple remains, and still operates from its original location on Pritchard Avenue. The James Street Labor Temple continued to operate, at least until the 1960s. In 1957, it was reported that the building could no longer accommodate all unions it represented and as a result, the James Street Labor Temple was seeking a larger, more adequate space. The James Street Labor Temple was demolished, possibly by fire, in 1966.

Click here to see former James Street Labor Temple location on map.

Click here to see Ukrainian Labor Temple on map.

Click here to see former Liberty Temple location on map.

Image Source: James Street Labor Temple. Still Images Section, item 1, negative 10056. AM.du

![Majestic Theatre. Source: City of Winnipeg Archives. Board of Control [File 10505]](http://1919strike.lib.umanitoba.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/F0001_0178_0000_00000_10505_002-300x300.jpg)

Previous

Next

Outside of Winnipeg

All municipalities in Greater Winnipeg were affected by the General Strike in one way or another. Shared services, such as streetcar and water services, bound the separate polities together; when streetcar operators walked off the job, it affected all municipalities, as did the absence of telephone operators, postal workers, and teamsters. However, this lack of services also made it more difficult for strikers from these areas to participate in the parades and rallies that almost always took place in Downtown Winnipeg. This didn’t stop everyone, however. Several of those arrested during Bloody Saturday and the June 10 riots were from outside Winnipeg proper. Many of the railway workers from the shops in the Town of Transcona went on strike, as did many from Brooklands, which was at the time part of the Rural Municipality of Rosser. It wasn’t just workers in private industries that went on strike: the municipal employees of the City of St. Boniface and the Rural Municipality of Assiniboia (including St. James) went on strike. Similar to civic employees in Winnipeg, volunteers were organized in St. Boniface and Assiniboia to perform civic services such as refuse removal and firefighting. Also similar to Winnipeg was the ultimatum offered to striking civic employees by their respective municipalities – if they didn’t sign a pledge not to engage in large scale labour action, they would be fired. The pledges they were required to sign were almost word for word facsimiles of the one used in Winnipeg, which was colloquially referred to as the “Slave Pact”. In the case of St. Boniface, strike leader Roger Bray – who lived in St. Boniface at the time – and the hundreds of the pro-strike veterans he led marched to St. Boniface City Hall on June 2 and demanded the City withdraw its ultimatum. He followed up on June 9, once again asking Council to rescind it.

Sympathy strikes took place outside the greater Winnipeg area as well. Strikes broke out in Vancouver, Calgary, Edmonton, Victoria, Toronto, Regina, Saskatoon, Amherst, and Brandon, as well as several smaller cities across Canada. Most of these were short lived, but the strike in Brandon lasted from May 20 to the end of June. In all these cases, as in Winnipeg, there were those that opposed the strike. The Brandon Law and Order League, for example, played a role in Brandon similar to that of the Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand in Winnipeg, while the town of Stonewall, Manitoba sent letters to municipalities around Manitoba, asking that they petition the Province to pass anti-strike legislation. Not all municipalities were anti-strike, however. The City of Transcona rejected the letter sent by Stonewall, stating that it believed living wages and good working conditions were more effective at preventing sympathetic strikes than coercive legislation. People all over the world were interested in the strike. Famous Italian socialist Antonio Gramsci wrote about the General Strike (Kramer and Mitchell 2010, 8) and the University of California Berkeley wrote Mayor Gray personally to ask for copies of the Winnipeg Citizen.

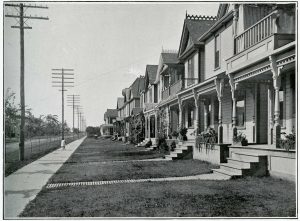

Image source: St. James, looking west from fire hall. COWA. Martin Berman Postcard Collection (vol. 4D).

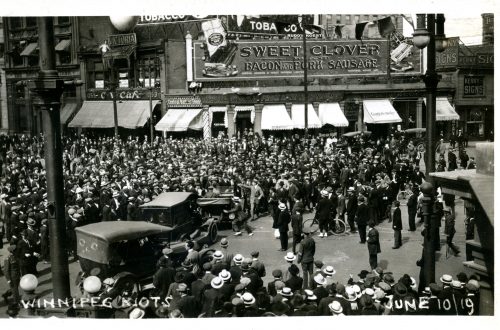

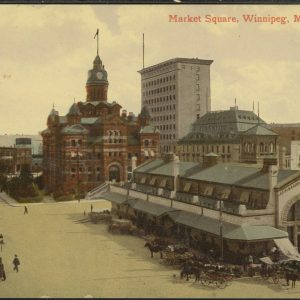

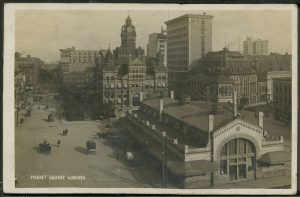

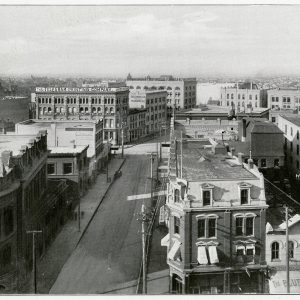

The Market Square of 1919 is not the same Market Square that now sits between King Street, Bannatyne Avenue, and William Avenue. The original Market Square was behind City Hall, between King and Princess Streets, where the Public Safety building currently stands. In 1889, a public market building was erected behind City Hall, just north of William, facing Market Street (currently Market Avenue, which at the time extended west passed City Hall). This area became known as Market Square. In addition to being a centre for trade, Market Square was used to hold events and ceremonies, such as marches by troops off to serve in the First World War, and as a gathering place.

The Market Square of 1919 is not the same Market Square that now sits between King Street, Bannatyne Avenue, and William Avenue. The original Market Square was behind City Hall, between King and Princess Streets, where the Public Safety building currently stands. In 1889, a public market building was erected behind City Hall, just north of William, facing Market Street (currently Market Avenue, which at the time extended west passed City Hall). This area became known as Market Square. In addition to being a centre for trade, Market Square was used to hold events and ceremonies, such as marches by troops off to serve in the First World War, and as a gathering place.

Even before the General Strike, Market Square saw conflict. On January 26, 1919, some labour leaders had planned to hold a memorial for two German socialists who had recently died, but the meeting never took place. A group of veterans marched into Market Square and began a series of violent actions perpetrated against those of Central and Eastern European descent. During the strike itself, Market Square was often used by strikers and pro-strike veterans as a muster point, either prior to a march, or at its conclusion. The first march of the pro-strike veterans to the Legislature on May 31 began in Market Square. This was not the last time these veterans made use of Market Square. After the June 17 arrest of Roger Bray, their nominal leader, his successors called for nightly meetings in Market Square. One of these meetings, on June 20, was to plan the silent parade that would become Bloody Saturday.

After the strike, labour still had a presence in Market Square, often used as a gathering point for May Day parades. The market building was demolished in 1964-65 and the whole area was restructured as part of the erection of the current City Hall and the Public Safety building. An attempt at rejuvenation in the 1970s applied the name “Old Market Square” to a large area around the original Market Square. However, with the introduction of the “Exchange District” moniker in the 1980s, “Old Market Square” fell out of use and became associated specifically with the park that currently bears that name.

Click here to see former location on map.

Image Source: COWA. Martin Berman Postcard Collection (vol. 4C).

Cut off from the rest of Winnipeg by the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) yards that run the length of it, the North End developed, to some degree, apart from the rest of Winnipeg and suffered from rampant poverty, inadequate housing, and overcrowding. This was not always the case. Prior to the construction of the CPR yards in the 1880s, Point Douglas was one of the most desirable residential neighbourhoods in Winnipeg and was home to several of Winnipeg’s business elite. However, the railway had attracted a large influx of workers who made homes in the North End, which, in addition to the noise and pollution created by railway and heavy industry, caused much of the business elite to move elsewhere. By 1895, the North End had become distinctly working class. With few crossings, the rail lines physically separated the North End from the rest of Winnipeg, effectively isolating it. This did not stop the North End from attracting residents, however, and it became one of the most densely populated areas of the city. The lack of space and housing led to cramped living conditions and dwellings of generally subpar quality.

Cut off from the rest of Winnipeg by the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) yards that run the length of it, the North End developed, to some degree, apart from the rest of Winnipeg and suffered from rampant poverty, inadequate housing, and overcrowding. This was not always the case. Prior to the construction of the CPR yards in the 1880s, Point Douglas was one of the most desirable residential neighbourhoods in Winnipeg and was home to several of Winnipeg’s business elite. However, the railway had attracted a large influx of workers who made homes in the North End, which, in addition to the noise and pollution created by railway and heavy industry, caused much of the business elite to move elsewhere. By 1895, the North End had become distinctly working class. With few crossings, the rail lines physically separated the North End from the rest of Winnipeg, effectively isolating it. This did not stop the North End from attracting residents, however, and it became one of the most densely populated areas of the city. The lack of space and housing led to cramped living conditions and dwellings of generally subpar quality.

Attracted by the cheap housing and the jobs provided by the CPR Yards and the heavy industry they brought with them, the North End became home to the vast majority of Winnipeg’s Eastern European immigrants including Ukrainians, Jews, and Poles, as well as a significant population of Black Canadians who worked as sleeping car porters on the rail lines. For this reason, the North End was sometimes referred to as “The Foreign Quarter” or “New Jerusalem”. These groups were generally marginalized and subjected to considerable prejudice, but despite this, the intersection of cultures in the North End created a strong community with its own distinct identity. Selkirk Avenue and North Main in particular were hubs of activity and commerce. Many people of British descent also lived in the North End, but they were generally confined to the northeast area around St. John’s School and St. John’s Anglican Church.

Many community support organizations developed in the North End, several of which had pro-labour agendas, such as the Jewish Arbeiter Ring, and the Ukrainian Social Democratic Party. Several labour temples such as the Ukrainian Labor Temple and the Jewish-run Liberty Temple operated out of the North End, as did several pro-labour newspapers such as Czas and the Ukrainian Voice. Some support organizations run by those of British descent, such as the All People’s Mission run by Rev. J.S. Woodsworth, also operated out of the North End.

Like the Northend, Elmwood, across the river from Point Douglas and St. John’s, was similarly a working class neighbourhood defined by the railway. Originally part of the Rural Municipality of Kildonan, Elmwood voted to join the City of Winnipeg in 1906 to secure city services that the mostly rural RM couldn’t provide. The area had become far more urbanized than the rest of Kildonan due to its proximity to the CPR line and Point Douglas, which brought in a substantial amount of medium and heavy industry

Several of those arrested on June 17 during the General Strike lived in the North End including Aldermen A.A. Heaps and John Queen, and Rev. William Ivens, and the offices of several pro-labour immigrant organizations including the Liberty and Ukrainian Labor Temples were raided.

The North End and Elmwood were divided into three wards. Ward 5, represented by Aldermen John Queen and A.A. Heaps, encompassed the area south of Burrows Avenue; Ward 6, represented by Aldermen R.H. Hamlin and W.B. Simpson, encompassed the area north of Burrows, up to the City limit; and Ward 7, represented by Aldermen Alex. McLennan and J.L. Wiginton, encompassed the entirety of Elmwood.

Image Source: COWA. Committee on Public Health and Welfare (A618 File 855).

Prior to being annexed by the City of Winnipeg in 1882, the area south of the Assiniboine River was part of the Parish of St. Boniface and was called St. Boniface West. The area remained largely agrarian until the late 1800s and early 1900s, when it began to be urbanized. Prior to 1883, there was only a private toll bridge connecting the south to the rest of Winnipeg, making it relatively undesirable to those who worked in the urban core. The Osborne Street Bridge was constructed in 1883, the Maryland Street Bridge in 1894, and, replacing the private bridge, the Main Street Bridge in 1897. As Winnipeg’s core began to develop and became increasingly crowded, many of those who could afford it began to search for other areas of the city to live in. Real estate developers were aware of this and attempted to cater to this demographic by keeping lots large and imposing building requirements that few but the wealthy could afford.

Crescentwood, located across the Assiniboine from Armstrong’s Point, was at the time of the General Strike, home to Winnipeg’s wealthiest business owners. First developed by Charles Enderton in 1902, Crescentwood became one of the first suburbs of Winnipeg marketed exclusively to the rich. Its feature street, Wellington Crescent, was lined with mansions and was home to some of Winnipeg’s wealthiest, including A.J. Andrews, Isaac Pitblado, A.K. Godfrey, and other members of the Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand. Many in Crescentwood genuinely feared a Bolshevik uprising was imminent, especially after June 4, when a group of 2,500 veterans marched down Wellington Crescent in support of the strike. The residents of Crescentwood were so alarmed they began to organize and drill volunteer patrols and set-up a secondary phone line in case the strikers cut the first.

In contrast to the ubiquitous extravagance of Crescentwood, Fort Rouge, to the east, was more economically diverse. While the mansions of wealthy business magnates lined the streets in some parts of the Roslyn and McMillan areas, Fort Rouge was also home to sizeable middle and working class populations, the latter of which lived primarily around the Canadian Northern Railway shops. In addition to all this, a notable population of Métis had moved into Fort Rouge prior to the encroachment of Winnipeg settlers. Unofficially called “Rooster Town”, their homes, which more closely resembled those of the North End than those of surrounding Fort Rouge, were located in a few clusters on the outskirts of the City.

In 1919, the entirety of Winnipeg south of the Assiniboine River made up Ward 1, which was represented by Aldermen I. Cockburn and J.K. Sparling.

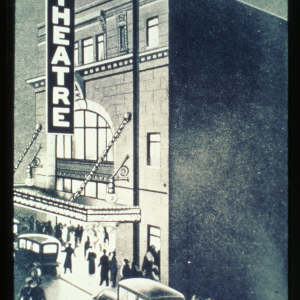

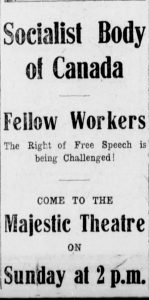

In the 1910s, Winnipeg theatres, like most theatres, brought plays, ballets, orchestral concerts, and other artistic performances to the city, but they also offered spaces for exchanging ideologies and political opinions. In 1915 Winnipeg’s New Grand Theatre hosted a play by Sam Blumenberg, who used the medium to express his political and anti-war views through shows such as “War – What for?”. The Columbia Theatre hosted him, alongside George Armstrong, to speak at a public event on “The Russian Bolsheviki” in 1918 (The Voice, February 8, 1918). As they could accommodate larger crowds than labour temples and offices, theatres were ideal spaces for debates and meetings about politics and labour.

In the 1910s, Winnipeg theatres, like most theatres, brought plays, ballets, orchestral concerts, and other artistic performances to the city, but they also offered spaces for exchanging ideologies and political opinions. In 1915 Winnipeg’s New Grand Theatre hosted a play by Sam Blumenberg, who used the medium to express his political and anti-war views through shows such as “War – What for?”. The Columbia Theatre hosted him, alongside George Armstrong, to speak at a public event on “The Russian Bolsheviki” in 1918 (The Voice, February 8, 1918). As they could accommodate larger crowds than labour temples and offices, theatres were ideal spaces for debates and meetings about politics and labour.

In post-war Winnipeg, many theatres hosted meetings attended by people with left-leaning ideologies who believed in collective bargaining rights, better wages, and better working conditions: people who would go on to make headlines during the Winnipeg General Strike. The Walker Theatre (now the Burton Cummings Theatre at 364 Smith Street), was the site of one such meeting. The theatre, named after its manager, Corliss Powers Walker, in operation since 1906, was large enough to hold the 1,700 attendees who came to hear R.B. Russell, Fred Dixon, and Samuel Blumenberg speak at 2:30 pm, on December 22, 1918. Alderman John Queen acted as Chairman for the meeting, which discussed the Russian Revolution and German Socialist Karl Liebknecht, who, unknown to the crowd at the time, would be executed alongside Rosa Luxemburg within the next month. The meeting was further meant to protest the detention of political prisoners and urge the Canadian government to withdraw troops from Russia.

The meeting closed with John Queen leading the crowd into cheers for the Russian Revolution. At its conclusion, the crowd dispersed peacefully and orderly and went on with their usual business. The meeting had, however, caught the attention of the Royal Northwest Mounted Police, who had sent a military intelligence agent, Sergeant Major Francis Langdale, to take notes. These notes would later be used in court to prosecute the Winnipeg General Strike leaders.

Less than a month later, meetings organized by the Socialist Party of Canada were held at the Majestic Theatre (363 Portage Avenue) on the afternoons of January 19 and 26, 1919. The Majestic Theatre opened in 1911 and was was later renamed the Rialto, and then the Downtown Theatre. It was demolished in the early 1980s to allow for the construction of Portage Place Mall. In 1919, the Majestic Theatre was an impressive building which could accommodate up to 500 people. It was a suitable location for a meeting hosted by the Socialist Party of Canada led by the party’s leader, Samuel Blumenberg. The Trades and Labor Council initially agreed to co-sponsor the event on January 19, but withdrew just prior to the meeting. The meeting of January 26 served as a space to mourn the recent deaths of Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht and to discuss German revolution. It is believed that this meeting, in part, sparked the January 26-27 riots where establishments owned by or employing so-called enemy aliens were vandalized by a mob made up in part of returned soldiers.

During the strike, theatres were further used to boost morale and raise funds for the strikers. For example, a concert was held at Queens Theatre on June 13 in support of the strikers.

Click here to see former Walker Theatre location on map.

Click here to see former Majestic Theatre location on map.

Click here to see former Columbia Theatre location on map.

Image Source: An advertisement for the January 26, 1919 Majestic Theatre meeting. Winnipeg Tribune, January 25, 1919. UML.

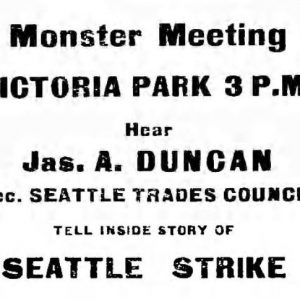

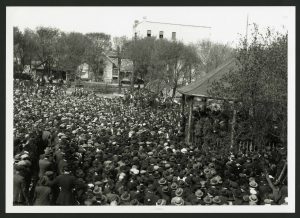

Purchased by the City in 1893 and named in 1900 after the Queen, picturesque Victoria Park sat nestled up against the river, between what is today Amy Street and James and Pacific Avenues. It was open, spacious, close to the James Street Labor Temple, close to City Hall and Market Square, and a relatively short distance from the North End, making it a perfect place to hold pro-strike rallies and sermons. The ability to gather thousands of strikers provided a way for the strike leaders to engage with them in a personal and participatory way that the Western Labor News couldn’t, helping both to keep them informed and increase morale.

Purchased by the City in 1893 and named in 1900 after the Queen, picturesque Victoria Park sat nestled up against the river, between what is today Amy Street and James and Pacific Avenues. It was open, spacious, close to the James Street Labor Temple, close to City Hall and Market Square, and a relatively short distance from the North End, making it a perfect place to hold pro-strike rallies and sermons. The ability to gather thousands of strikers provided a way for the strike leaders to engage with them in a personal and participatory way that the Western Labor News couldn’t, helping both to keep them informed and increase morale.

The park saw use almost immediately after the strike began. On May 16, strike leader William Ivens delivered the first of many sermons he would minister in the park. Ivens held service there every Sunday for the duration of the strike. Other events would take place almost daily, during which some of the other strike leaders such as Fred Dixon and J.S. Woodsworth would deliver their own speeches. These meetings were further used to raise money for relief efforts such as the Labor Café. Thousands of strikers would be present at these events. On June 12, one such gathering paid homage to the women of the strike, reserving seats up front for them while the men stood in the back.

Victoria Park not only acted as a locale to deliver speeches, but also as a rallying point for marches, such as those organized by Roger Bray and the pro-strike returned soldiers, whose rallies often began or ended in Victoria Park. One such march was planned for June 10, the day violence broke out on Portage and Main, but it was cancelled before it began. The pro-strike veterans used Victoria Park so often that it became known as the “Soldiers Parliament”.

The speeches and sermons by strike leaders ended when they were arrested on June 17. Though they were released on bail on June 20, it was on the condition that they give no more public speeches. Despite this, meetings still took place in Victoria Park. A protest took place in the park shortly after the strike leaders were arrested and a far more sullen and mournful gathering took place in the wake of Bloody Saturday. Though the strike had all but collapsed by June 24, one final gathering had begun in Victoria Park, only to be shut down when the City closed the park entirely.

Though contested by many, Victoria Park was sold in the 1920s to Winnipeg Hydro, which erected a steam heating plant on the site. The sale was orchestrated by none other than former strike leader A.A. Heaps. The steam heating plant was decommissioned in 1990 and most of the land was developed into condominiums and Waterfront Drive.

Though Victoria Park is most commonly associated with the Winnipeg General Strike, strike-related gatherings were held at parks across Winnipeg and in neighbouring communities. The Western Labor News often promoted upcoming mass meetings in its paper at parks, including Dufferin Park (Logan Avenue), Norwood Ball Park, St James Park, Weston Park, Elmwood Park, and St. John’s Park.

Click here to see former location on map.

Image Source: COWA. Parks and Recreation Photograph Collection (A67 file 15)

Western Winnipeg – including but not limited to what is now called “the West End” – was multifaceted during the strike. Certain pockets, such as Weston, were fiercely pro-labour, while others, such as Wolseley, were made up primarily of members of the business elite or middle class who were generally against the strike. Prior to Winnipeg’s boundary being extended to St. James Street in 1882, a large portion of what is now the western Winnipeg was part of the Parish of St. James. The area began to develop rapidly after 1895 and into the 20th century. Like much of Winnipeg outside of the North End, the residents of western Winnipeg were primarily British, though there was a notable population of Germans and Scandinavians who lived along Sargent and Ellice Avenues. Economically, the area was less homogenous.

Western Winnipeg – including but not limited to what is now called “the West End” – was multifaceted during the strike. Certain pockets, such as Weston, were fiercely pro-labour, while others, such as Wolseley, were made up primarily of members of the business elite or middle class who were generally against the strike. Prior to Winnipeg’s boundary being extended to St. James Street in 1882, a large portion of what is now the western Winnipeg was part of the Parish of St. James. The area began to develop rapidly after 1895 and into the 20th century. Like much of Winnipeg outside of the North End, the residents of western Winnipeg were primarily British, though there was a notable population of Germans and Scandinavians who lived along Sargent and Ellice Avenues. Economically, the area was less homogenous.

Those areas south of Portage Avenue tended to be wealthier than those north of Portage. The proximity to the Assiniboine River, the distance from industry, and Winnipeg’s pervasive north-south divide made these homes attractive to those who could afford them. Residents of neighbourhoods such as Wolseley and Armstrong’s Point (sometimes Armstrong Point) ranged from middle class shop keepers, factory foremen, and professionals to Winnipeg’s business elite. This area was the home of Ed Parnell, a Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand member, and likely that of several other members whose names were never made public.

Conversely, north of Portage, the West End was home to much of Winnipeg’s labour ‘elite’ – its skilled workers, union bosses, and those well versed in politics, including strike leaders R.B. Russell and R.J. Johns. It was, however, also home to a sizeable population of unskilled workers and labourers, but it differed from the North End in that these workers were primarily of British descent. The relatively cheap housing and proximity to large places of employment such as the Weston Shops and factories like Crescent Creamery and Speirs-Parnell Bakery attracted skilled and unskilled workers alike. Some of these neighbourhoods were fiercely pro-strike. The women who lived in Weston, for example, nestled just south of the CPR Weston Shops, had a reputation for giving the strike their all, so much so that an employee of T. Eaton’s Co. who attempted to cross the picket line testified in court that he’d rather “face the Huns than the women of Weston”.

In 1919, western Winnipeg was divided into three separate wards: Ward 2, represented by Aldermen F.O. Fowler and A.H. Pulford, primarily consisted of Winnipeg’s central core south of Notre Dame Avenue, but also extended west to Spence Street; Ward 3, represented by Aldermen H. Gray and Geo. Fisher, encompassed all the area west of Spence to the City limit and south of Notre Dame to the Assiniboine; Ward 4, represented by Aldermen A.L. Maclean and E. Robinson, was made up of all the area west of the Red River to the City limit, north of Notre Dame, and south of Point Douglas Avenue and the CPR yards.

Image Source: COWA. Photograph Collection (P3 file 5).

Other Notable Locations

Previous

Next

Canadian Pacific Railway Station

In 1919, the Canadian Pacific Railway Station was an entry point into Winnipeg for people from all walks of life. Through this station, immigrants that would face economic hardships, and discrimination started a new life in Canada. Politicians, sent to Winnipeg to intervene in the strike, further walked through the station on Higgins Avenue on their way to meetings with local politicians and organizations.

Click here to see former location on map.

Dominion Bridge Company was founded in Montreal in 1886 and its Winnipeg plant was built around 1906. Its core business was the manufacture of steel bridge components. It was located in Winnipeg’s West End, between Dublin and Saskatchewan Avenues and Midland Street. Leading up to and during the General Strike, the plant was under the purview of Norman Warren, Dominion Bridge Co.’s Western Manager. On May 2, its employees, along with most of the metal workers in the city, walked off the job, demanding better wages, conditions, and that Winnipeg’s large metal plants, including Dominion Bridge Co., recognized the Metal Trades Council. It bought out its competitor, Manitoba Bridge and Iron Works, in 1930. Over the years it was involved in several Winnipeg construction projects, including the St. James Bridge, the old Provencher Bridge, the Union Bank building, and the old Winnipeg arena and stadium. It also made shells during the Second World War. The company went bankrupt in 1998, but some of the original buildings are still standing.

Click here to see former location on map.

Built in the 1870s on land donated by the Hudson’s Bay Company at Osborne Street and Broadway, Fort Osborne Barracks served as the headquarters for Military District 10. General Ketchen and the militia were stationed here during the strike and were on alert in the event that violence broke out. On June 21, they were called upon by Mayor Gray, who drove from City Hall to the Barracks to request their assistance in dealing with the silent parade that had quickly escalated into a riot.

Click here to see former location on map.

Following the strike, it was rumoured that J.H. Ashdown Hardware Company had provided Special Police with wagon spokes and chair legs to be used as weapons against the strikers. The store’s owner, J.H. Ashdown, was both a member of the Manitoba Club and Board of Trade.

Click here to see former location on map.

The strike leaders who were arrested were held in Stony Mountain Penitentiary (outside of Winnipeg in Stony Mountain, Manitoba), as well as Vaughan Street Gaol (at Vaughan Street and York Avenue). On June 17, when strike leaders were arrested, arrangements were made to send them to Stony Mountain Penitentiary, instead of the Vaughan Street Gaol. The latter facility was too central those behind the arrests feared that the location would encourage gatherings, protests, and riots in the area. Those who were later convicted further served their sentences at the penitentiary, and at the Birch River Prison Farm (in the RM of Reynolds).

Click here to see Stony Mountain Penitentiary location on map.

Click here to see Vaughan Street Gaol location on map.

Click here to see former Birch River Prison Farm location on map.

Manitoba Bridge and Iron Works

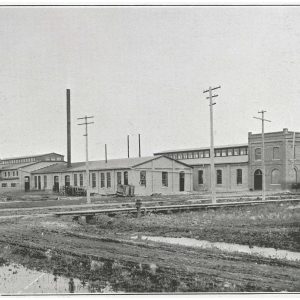

Occupying 15 acres of land at 875 Logan Avenue (primarily between Tecumseh and Arlington Streets) Manitoba Bridge and Iron Works was one of Winnipeg’s three major metal shops in 1919. Founded in 1902 by T.R. Deacon and H.B. Lyall, Manitoba Bridge and Iron Works supplied steel for several large scale projects, including the Legislative Building and Union Station, and made munitions during the First World War. In 1918, it purchased the Manitoba Rolling Mills in Selkirk, Manitoba. Its employees were involved in several strikes over the years, including on May 2, 1919 when they walked off the job as part of a larger strike in the metal works industry over wages, working conditions, and the validity of the Metal Trades Council. This helped lead to the General Strike.

In 1930, Manitoba Bridge and Iron Works was bought out by Dominion Bridge Co., one of Winnipeg’s other major metal shops. Its name was changed to Manitoba Bridge and Engineering Works and it focused on making products that did not compete with its parent company. It was finally dissolved in 1982, but some of the original buildings are still standing.

Click here to see former Manitoba Bridge and Iron Works location on map.

See also: Information on T.R. Deacon, founder of Manitoba Bridge and Iron Works, in Who: Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand

The Manitoba Club, located on Broadway between Main and Fort Streets, is a social club which, at the time of the strike, held among its all-male membership many of the Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand, as well as militia leader General Ketchen and prominent members of the business community. Most, if not all of its members, were opposed to the General Strike. The Manitoba Club was sometimes used as a meeting place by the Citizens’ Committee as well as others who opposed the strike.

Click here to see location on map.

During the strike, the Provincial Government was in a transition period, operating from two locations. The construction of the Legislative Building, as we know it today, began in 1913 and would be completed in 1920. Consequently, during the strike, representatives of the Provincial Government could be found at this building, as well as in the old building, on Kennedy street. As the government was reluctant to get involved in the strike, the Legislative grounds were frequently visited by parades of returned soldiers, aiming to force the government to intervene.

Click here to see Manitoba Legislative Building (1884-1920) on map.

Click here to see Manitoba Legislative Building (1920 to present) on map.

The “Royal Alex” was a popular meeting space during the strike. Located near the Canadian Pacific Railway station, the hotel accommodated guests such as Federal Ministers Arthur Meighen and Gideon Robertson and consequently, many strikers, returned soldiers, and local politicians frequented the hotel during the strike to meet with such representatives.

Click here to see former location on map.

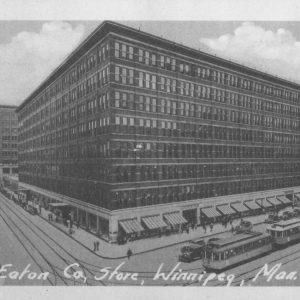

T. Eaton Company (“Eaton’s”) was a large national department store that opened its Winnipeg location in 1905 on Portage Avenue, between Donald and Hargrave Streets. Anticipating the strike, Eaton’s made arrangements to hire labour to replace striking workers. However, they had arranged to hire labour from outside of Winnipeg and, as railway workers across Canada supported the Winnipeg General Strike, the new workers on their way to Winnipeg were prevented from boarding the trains. In another attempt to undermine the strike, Eaton’s supplied bats and horses for authorities trying to break the strike. There were approximately 500 women from Eaton’s who walked out. Not all were re-hired after June 26. Eaton’s was demolished in 2002 to make way for a new sports arena.

Click here to see former location on map.

Vulcan Ironworks was a large metalworking shop occupying several city blocks in Point Douglas, around Sutherland Avenue and Maple Street. Employees from Vulcan Ironworks went on strike on May 2, 1919, as part of a larger strike in the metalworks industry over wages, working conditions, and the validity of the Metal Trades Council. In 1919, Vulcan Ironworks was operated by L.R. Barrett, and his brother E.G. Barrett. This walkout, unresolved for two weeks, was one of the disputes that lead to the General Strike. In the aftermath of the strike, Vulcan Ironworks continued to be a major employer in Winnipeg. In 1947, the company was purchased by James A. Gairdner, of Toronto, and became Vulcan Iron and Engineering Ltd. In 1955, the company became a western division of Bridge and Tank Company of Canada and was renamed Bridge and Tank Western Ltd. in 1958. The company moved out of Point Douglas in 1961.