Law Enforcement

The Winnipeg Police Department

As a whole, law enforcement was pro-strike, anti-strike, and neutral, all at the same time, and its evolution as the strike went on had significant consequences.

The Policemen’s Union voted in favour of striking during the General Strike. Unlike others, however, the police did not leave their positions. Rather, the Strike Committee asked that they continue in their roles, as the former feared the removal of the police would be cause for implementing martial law. As such, the police continued to function, but they were generally sympathetic towards the strikers, and the Strike Committee made it known that they could be called out if necessary.

In response, the Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand began to organize a volunteer police. As early as May 23, private citizens with armbands identifying themselves as Special Police were on the streets. The Police Commission, chaired by Alderman Sparling, was not in favour of this kind of volunteer police work, but the City had been slowly appointing Special Constables in case the police did walk out. These Specials were sworn in by the City Clerk and also wore Special Police armbands.

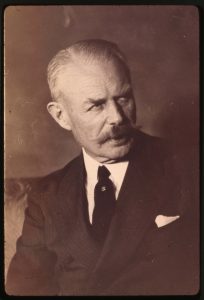

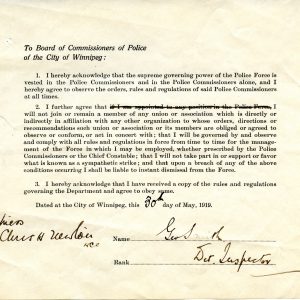

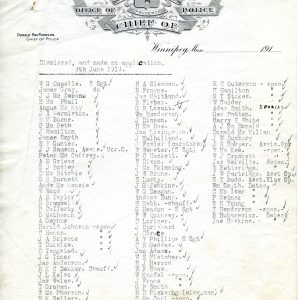

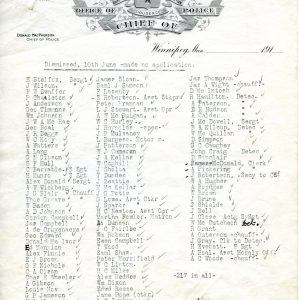

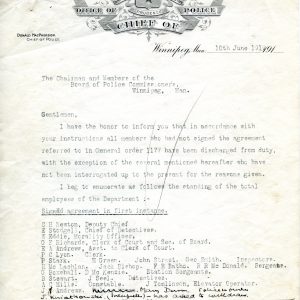

Meanwhile, on May 29, the police were given an ultimatum by the Commission: they were either to sign a loyalty oath, forbidding them from striking or be dismissed. This pledge came to be known as the Slave Pact. Over 20 signed, but most refused. On June 9, the Commission followed through and dismissed the 217 employees who had refused to sign the oath. They were replaced by the Specials, under the command of Major Hilliard Lyle. A mounted unit made up of returned soldiers was also formed under Captain James Dunwoody. Along with these men, Police Chief Donald MacPherson was replaced by Deputy Chief Chris Newton on June 11. The Commission asked MacPherson to take a 3 month leave of absence, but he refused, and was let go as a result.

The oath of allegiance given to police, as well as records to the Chairman and members of the Board of Police Commissioners listing the police officers who were dismissed or who stayed on. Winnipeg Police Museum.

The Specials’ first night out in force on June 10 led to a riot as they, armed with wagon spokes and chair legs rumoured to have been provided by J.H. Ashdown Hardware Company and T. Eaton Company, clashed with protestors, leading to several injuries and arrests. Referring to their bats and use of force, the Western Star once stated that the “Specials are becoming regular baseball fans” (Western Star, 1919-06-24). On paper, the Special Constables numbered over 1,300, but in reality there were only two or three hundred on the streets, most of whom were inexperienced in police work. During that first day on the streets, the Specials proved to be ineffective and Major Lyle was replaced with Major Bingham, whom the Citizens supported.

Police Chief Newton was often present at meetings held between the Citizens’ Committee and the higher Provincial and Federal authorities. Newton took part in coordinating the June 17 raid in which several leaders of the strike were arrested. On Bloody Saturday, after the RNWMP had charged the crowd and it began to disperse, Special Constables began blocking off sections of Main Street. A contingent trapped some of the fleeing crowd in an alley between James and Market Avenues, and a particularly violent mêlée ensued. This alley became known as Hell’s Alley.

After the strike had concluded, the police who had been dismissed began to return to work and sign the Slave Pact. Many of those who stayed on during the strike were given bonuses. The Special Police were decommissioned on July 2 by order of the Police Commission. Their creation and conduct was a talking point during the trials of the strike leaders that followed.

Royal Northwest Mounted Police

RNWMP on Bloody Saturday. COWA. Photograph Collection [P44 File 16]

The Royal Northwest Mounted Police (RNWMP) were formed by Prime Minister John A. MacDonald in 1873 to police the Northwest Territories (then most of Western Canada), to check American encroachment, and to assist in carrying out the segregation, assimilation, and attempted destruction of Indigenous peoples. By 1919, in the wake of the Red Scare that followed the 1917 Russian Revolution, the RNWMP were heavily involved in monitoring and infiltrating suspected Bolshevik and radical organizations. One RNWMP agent who had infiltrated the Socialist Party of Canada went so far as to have himself arrested in order to maintain his false identity as an American Industrial Workers of the World member named Harry Blask. RNWMP spies infiltrated the Western Labor Conference, held in Calgary in March 1919, and reported back to RNWMP headquarters in Regina that radicals sought to use the One Big Union and general strikes to overthrow the establishment (Bumsted 1994, 115). Another spy, Francis E. Langdale, infiltrated the Walker Theatre meeting in December 1918 and reported back about several statements he believed were seditious. Reports were made about other worker and socialist gatherings leading up to the General Strike. The reports of these agents were later used as evidence in the sedition trials and immigration hearings that followed the arrests of several strike leaders on June 17.

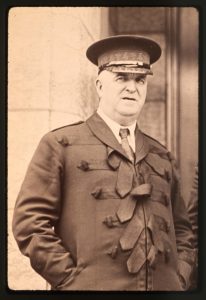

On May 17, 1919, two days after the strike began, the Attorney General of Manitoba requested assistance from the RNWMP in the event violence broke out. The RNWMP were commanded by Commissioner A.B. Perry in Regina, and its Winnipeg detachment was commanded by Col. Cortlandt Starnes. Perry was deeply suspicious of socialists. He once commented that “I am not prepared to say that they are aiming at revolution, but…some day they would be unable to control” (Bumsted 1994, 109). Though the RNWMP were under federal jurisdiction, Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand member A.J. Andrews wielded considerable influence over their actions. Early in the strike, Acting Minister of Justice Arthur Meighen made Andrews his representative in Winnipeg, an ambiguous title that allowed him to confer with the RNWMP and even direct their actions on occasion. It was Andrews and the Citizens who, on June 17, orchestrated the RNWMP arrests of several of the strike’s leaders, as well as five “enemy aliens”, four of whom had little to do with the strike. Two of the men arrested that day were done so in error. Rev. S.O. Irven was mistaken for William Ivens, whom he had succeeded as Minister of McDougall Church, while Mike Verenczuk was mistaken for Boris Devyatkin, whose home he was staying at. Though he had to use a marriage register as proof, the Anglo-Saxon Irvin was able to convince the RNWMP of his true identity without much difficulty. The Russian born Verenczuk, on the other hand, was jailed for 17 days before finally being released. In addition to this, several labour temples and the offices of immigrant organizations were raided. Col. Starnes himself locked down the James Street Labor Temple while it was being raided.

The most iconic role played by the RNWMP took place on June 21, Bloody Saturday. The previous evening, pro-strike returned soldiers had planned to hold a silent march. The next morning, Commissioner Perry took part in a meeting in which he, Mayor Gray, Minister Robertson, and A.J. Andrews attempted to persuade the returned soldiers to abandon their parade. They were unsuccessful, however, and the march began as scheduled. A crowd of strikers, sympathizers and general onlookers assembled in front of City Hall to watch the parade, leading Mayor Gray to call on the RNWMP. Many of the RNWMP who arrived were returned soldiers who had joined up almost immediately after coming home. They wore khaki rather than traditional RNWMP uniforms and were particularly despised by the pro-strike returned soldiers. There are several different accounts of exactly what happened on Bloody Saturday, but at one point, the crowd attempted to derail a streetcar, causing the RNWMP to charge through the crowd multiple times, using their clubs while having bricks and rocks thrown at them. During one of the charges, the RNWMP abruptly turned onto William Avenue and fired their revolvers into the crowd. The crowd dispersed, but the RNWMP remained in the area into the evening. By the time it was all over, dozens were wounded and one was killed, followed by another who died of his wounds two days later.

During the immigration hearings of the arrested “enemy aliens” and the sedition trials of the arrested British strike leaders, multiple RNWMP were called as witnesses. Francis E. Langdale, for example, testified about what he had witnessed at the Walker Theatre meeting in 1918. In 1920, the RNWMP merged with the Dominion Police to form the Royal Canadian Mounted Police.

Militia

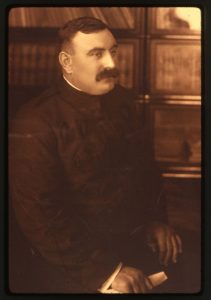

General Huntley Douglas Brodie Ketchen (1872-1959)

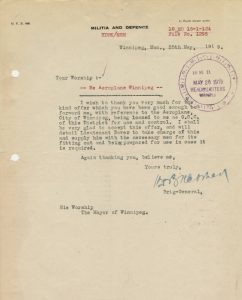

H.D.B. Ketchen was born on May 22, 1872 in India, where his father, Major-General James Ketchen, was on active duty. Born in a military family, H.D.B. Ketchen was educated in England at the Royal Military College. After a few years serving in the British Imperial Army, Ketchen moved to Canada in 1894, joining the ranks of the Royal Northwest Mounted Police and settled in Winnipeg. Prior to the Winnipeg General Strike, Ketchen saw military service during the Boer War and the First World War. Following the First World War, and just prior to the Winnipeg General Strike, Ketchen was appointed to Military District no. 10 – Winnipeg – where he served as General Officer Commanding. Though Ketchen attended some meetings at Victoria Park and addressed the crowd there on occasion, adopting a neutral and friendly tone, he also shared common traits with the members of the Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand, having attended some of their meetings, sharing member status at the Manitoba Club, and living amongst some of the members in Crescentwood. He did not believe that the strikers themselves were a threat to the government – whether it be municipal, provincial or federal – but he still believed that there was an anti-alien, Bolshevik element that might influence the events for the worse, leading him to push for the arrest of strike leaders. As the strike was more seriously perceived by governments as an attempt to overthrow the government, Ketchen was given more resources to keep the peace in Winnipeg during the strike. Mayor Gray provided him with access to an airplane if needed, while the Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand helped him recruit a citizens’ army, ready to be called on from Fort Osborne Barracks should there be a need. The militia further received added weaponry, with the delivery of machine guns shortly after the strike began. On numerous occasions, Ketchen, alongside other politicians, was pressured to declare martial law, though it never came to that.

As chaos erupted on Bloody Saturday, Mayor Gray read the riot act as the Royal Northwest Mounted Police tried to control the crowds. As shots were fired, he left the scene of the riot, driving to Fort Osborne Barracks to request assistance from Major Ketchen. Ketchen and the militia went to the scene, alongside Mayor Gray as Chief Magistrate. The Mayor’s presence alongside the militia was meant to signal that Ketchen’s arrival on the scene was not a declaration of martial law. Civil law still reigned. The militia drove through the riot in multiple cars in trucks, each carrying numerous men armed with rifles and bringing with them a machine gun to set-up on Portage and Main. They continued to patrol the area, even after the riot had dissipated, until after 11 pm that night. The militia under Ketchen’s command were described as soldiers from the 90th Winnipeg Rifles, the 100th Winnipeg Grenadiers, the 79th Cameron Highlanders, and the 106th Light Infantry regiments. They were further described as members of the middle class (Winnipeg Tribune, June 23, 1919).

Following the strike, Ketchen successfully ran as a Conservative representative for Winnipeg’s 1932 Provincial election and held the seat for the two subsequent elections. Ketchen died in Winnipeg on July 28, 1959. He is buried at St. John’s Cathedral.

![RNWMP on Bloody Saturday. Source: City of Winnipeg Archives. Photograph Collection [P44 File 16]](https://1919strike.lib.umanitoba.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/C0013_0000_0000_P0044_0016_013.jpg)

![RNWMP on Bloody Saturday. Source: City of Winnipeg Archives. Photograph Collection [P44 File 16]](https://1919strike.lib.umanitoba.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/C0013_0000_0000_P0044_0016_008-1024x652.jpg)