Women

At 11 am, on May 15, 1919, approximately 30,000 workers in Winnipeg went on strike, marking the official start of the Winnipeg General Strike. By that time, many women working as telephone operators, had already been on strike for four hours. These ‘Hello Girls’, as they were sometimes known, were absent from their places of work at the beginning of their 7 am shift. Women working in retail, in offices, as laundresses, and so on, soon joined the strike. Furthermore, as telephones were a provincial service, many women outside of Winnipeg went on strike in sympathy with others.

At 11 am, on May 15, 1919, approximately 30,000 workers in Winnipeg went on strike, marking the official start of the Winnipeg General Strike. By that time, many women working as telephone operators, had already been on strike for four hours. These ‘Hello Girls’, as they were sometimes known, were absent from their places of work at the beginning of their 7 am shift. Women working in retail, in offices, as laundresses, and so on, soon joined the strike. Furthermore, as telephones were a provincial service, many women outside of Winnipeg went on strike in sympathy with others.

While many women went on strike, others came in to replace them. Many women acted as ‘scabs’ during the strike as employers sought to replace their striking workforce. Advertisements seeking “applications from bright, healthy, ambitious young women” to replace the striking telephone operators were published throughout the duration of the strike (Winnipeg Tribune, June 5, 1919). In many cases, employers paid their scabs a better wage than they had the striking workers prior to May 15. However, from the employers’ perspectives, they weren’t hiring scabs. Replacement workers were often described as paid volunteers, or, following some ultimatums, permanent employees.

Whether women were on strike or replacing striking labour, they faced persecution from all sides. One newspaper reported that six female telephone operators from Carman, Manitoba, came to Winnipeg after they went on strike as life in their hometown had become “unbearable” (Western Labor News, June 14, 1919). Other reports referenced strikers attacking scab labour and their equipment. In one report, it was claimed that women from Brooklands and Weston formed an organization with the aim of intimidating people who were not on strike, and had vandalized department store delivery rigs and attacked the drivers and Special Police (Winnipeg Tribune, June 6, 1919).

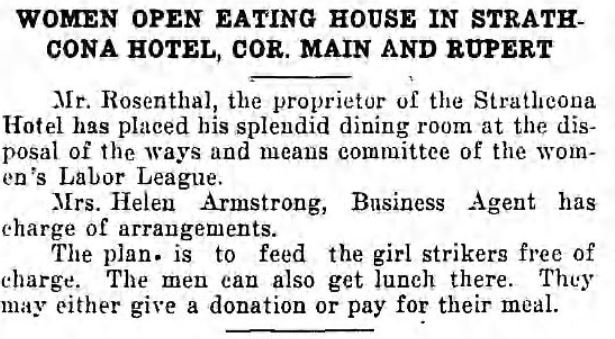

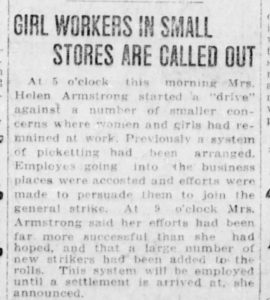

Support for women affected by the strike was offered in many ways. Whether they were themselves on strike, or struggling to support their families during the strike, women could obtain free meals through a kitchen organized by the Women’s Labor League. Meetings at Victoria Park often included a collection, with money donated by attendees to support the food kitchen. The Young Women’s Christian Association provided accommodations for women who needed shelter during the strike. These women-led organizations were closely tied with the labour movement, even before the strike. In fact, many prominent women in the suffragist movement, such as Winona Flett Dixon, Katherine Ross Queen and Helen Jury Armstrong, not only participated in the labour movement themselves, but also had to support their families during and after the strike, as their husbands – Fred Dixon, John Queen, and George Armstrong – were arrested and put on trial for their roles during the strike.

Outside of the workforce, women were also responsible for preparing their households. On May 14, one day before the General Strike, stores were reported to be crowded with female shoppers preparing for what they believed would be a long strike. In a recollection by the family of Wallace Brown, a Special Policeman during the strike, it was noted that “food was kept in Bunty’s baby carriage and hidden down by the river, just in case” (Hiebert Brown Family fonds, UMASC). While many were worried that the strike would limit access to essential services, many women ensured they were prepared before the strike started, stockpiling food supplies, cooking and preserving foods in preparation of gas supplies being cut off, and filling their bathtubs with water as the water supply would be limited during the strike.

Beyond playing a direct role in the strike, women were also used in anti-strike rhetoric by numerous news sources and politicians to illicit sympathy by the anti-labour movement. Many articles in the Winnipeg Citizen and the Winnipeg Telegram would remind readers of the starving women and children, while politicians such as Mayor Gray would, in anticipation of a scheduled parade or gathering, emphasize that women participated in such events at their own personal risk. Imagery of women fainting at the sight of the riots on Bloody Saturday were further used to elicit sympathy from readers of the Winnipeg Telegram. Paradoxically, newspapers juxtaposed this depiction of women with hostile, murderous and intimidating women who were pro-strike (Winnipeg Tribune, June 6, 1919). Though the narratives of the Winnipeg General Strike downplay the roles of women, a closer look shows that women were involved in every aspect of the strike. Whether they planned for it, supported it, or fought against it, they did so actively and boldly.

For a biography on Helen Armstrong, see Who: Strike Leaders.

Notable Women

Appointed to the Central Strike Committee on May 26, Helen Armstrong further assisted with the food kitchens at the Labor Café.

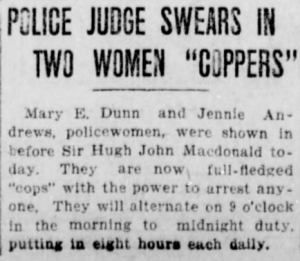

One of the first two police women appointed in Winnipeg, Mary Dunn stayed on duty after signing the Slave Pact following an ultimatum by the Police Commission.

Edith Hancox was a member of the Women’s Labor League, supporter of the Labor Church, and a speaker at Victoria Park.

Ethel Johns was a Children’s Hospital nurse who allowed strikers to enter the hospital to deliver milk. She was forced to resign due to anti-strike sentiments in the hospital and subsequently left Winnipeg to find other employment opportunities.

Mary Jordan was the secretary for the Winnipeg Labor Council and One Big Union.

Jessie Kirk was active in the labour movement. She lost her teaching job over her involvement with this movement and ran as a labour candidate for the Winnipeg School Board in 1919. In 1920, she won the provincial nomination of the Dominion Labor Party, but withdrew so that the jailed strike leaders could run. She became the first female City Coucillor in 1921.

Along with Margaret Steinhaur, Ida Kraatz was fined $5 and costs for damages by police for tearing up newspapers being sold by two female “scabs” under the advice of Helen Armstrong.

Genevieve Lipsett Skinner was a journalist during the strike who wrote an incriminating article based on her interview with John Queen, which was published in the Winnipeg Telegram. She testified about it during the strike trials. The defense argued that the interview never happened and was based on hearsay.

Along with Helen Armstrong, Mrs. W.H.C. Logan was one of two women who attended the Calgary convention as a delegate representing the Women’s Labor League.

Doris Meakin was a business agent for the Telephone Operators’ union and representative of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers.

Mrs. Niblett was a reporter who corroborated the story of Genevieve Lipsett Skinner against John Queen during the strike trials.

Katherine Ross Queen was a member of the Women’s Labor League who succeeded Helen Armstrong as president of the organization. Her husband, John Queen was arrested and convicted as a strike leader.

During the strike, Mary Dawson Snider was a reporter for the Toronto Evening Telegram – the first female reporter for the newspaper and the only female reporter to come from outside the city to report on the strike. She mainly reported favourably on the activities of the Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand, writing fourteen dispatches throughout the events. She was in Winnipeg from May 22 to June 10, 1919. She was one of the original members of the Canadian Women’s Press Club as well as the Toronto Women’s Press Club.

Along with Ida Kraatz, Margaret Steinhaur was fined $5 and costs for damages by police for tearing up newspapers being sold by two female “scabs” under the advice of Helen Armstrong.

Olga Tsurkalenko-Hunka was a member of the Ukrainian Labor Temple and a volunteer at the Labor Café.

Mrs. Webb was the chairman of the Women’s Labor League’s Relief Committee. She helped to fund the Labor Café.