Media

Pritchard paid his respects to the daily press of the country, saying “it is illiterate, untruthful, and ignorant.” […] “Why, I have met blackened, scarred miners who could write better editorials on international affairs with their picks.

– Strike leader W.A. Pritchard, as quoted in the Winnipeg Tribune, March 20, 1920.

Newspapers and the Strike

During the Winnipeg General Strike, few newspapers maintained a neutral view. Many of the major papers, such as the Winnipeg Tribune, the Manitoba Free Press, and the Winnipeg Telegram (all located on “Newspaper Row”, along McDermot Avenue) showed biases against strikers, to the point that they were banned from attending Winnipeg Trades and Labor Council (WTLC) meetings, as the WTLC accused these papers of distorting the facts.

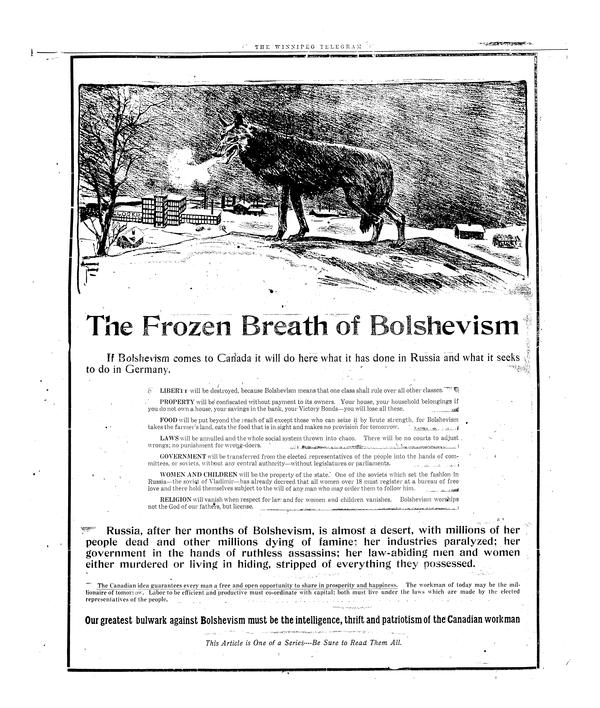

Many of these newspaper dailies in Winnipeg were briefly shut down on May 16, when newspaper typographers and pressers joined the strike, which did not win the strikers any favours in the eyes of newspaper editors and owners. Overall, very few newspapers looked favourably on the strike. Some were pro-labour, but did not believe that a General Strike was the means to improve working conditions. Others were strongly opposed to both labour and the strike, and were more blatant in their criticisms. The Winnipeg Telegram, and the Winnipeg Citizen (the latter published specifically to address the strike from the viewpoint of the Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand) were most against the strike. Their rhetoric often emphasized the role of Bolsheviks, Reds, and radicals, and blamed immigrants, or so-called enemy aliens, for the strike.

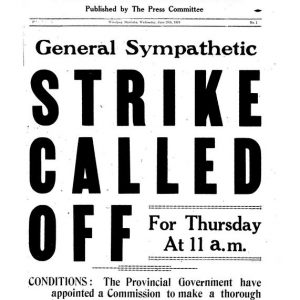

The most pro-strike paper in Winnipeg was the Western Labor News, published by the WTLC and the Strike Committee. During the strike, the Strike Committee regularly published a special Strike Bulletin edition of the Western Labor News. In this paper, the wealth and corruption of the Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand was often emphasized, with headlines like “Enemy Plans Exposed ($1,000,000 to Crush Strike)” (Western Labor News, June 10, 1919). It further tried to distance itself from the rhetoric of anti-strike papers, insisting that it was in support of deporting undesirable aliens, and emphasizing the presence of returned soldiers among strikers, to counter claims that the strike was led by enemy aliens and workers who had not fought in the war (Western Labor News, June 7, 1919).

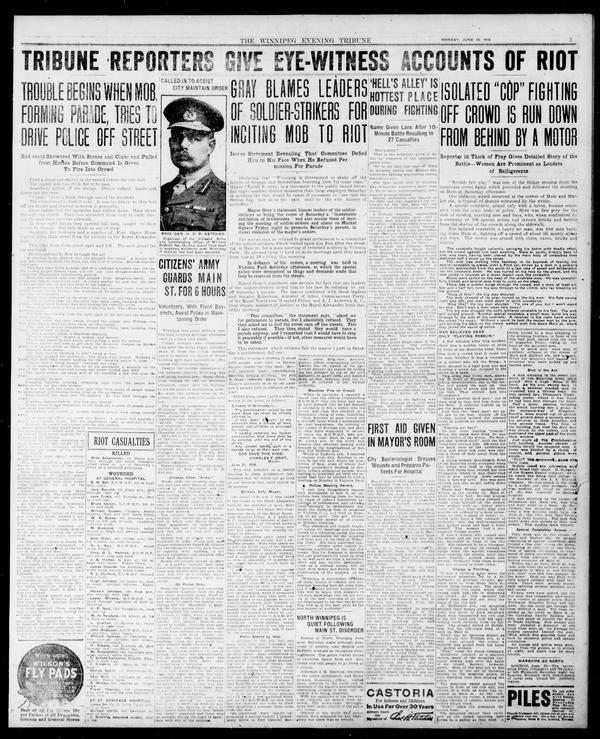

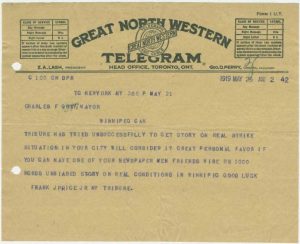

Regardless of these biases, one thing is indisputable: newspapers played an important role in shaping and influencing the views of the public. Furthermore, finding a neutral source was not only a difficult prospect in Manitoba, but outside of Manitoba as well. In one example, the New York Tribune sent a telegram to Mayor Gray, requesting an unbiased account of the strike, stating it has “tried unsuccessfully to get [the] story on [the] real strike”. Overall, while newspapers provide a great source for a retrospective study of the strike, their day-to-day accounts of events should always be read critically and taken with a grain of salt. It should also be noted that newspapers in 1919 did not publish on Sundays, meaning that the events of the strike’s most pivotal moment – Bloody Saturday – were not reported until the following Monday in all Winnipeg papers.

For more information on media and race, see Who: Racialized Communities.

Manitoba Free Press

The Manitoba Free Press, known today as the Winnipeg Free Press, was first published in 1872, making it the oldest daily newspaper in Western Canada. At the time of the strike, the Manitoba Free Press operated from Newspaper Row under the ownership of Clifford Sifton. Though its printing was briefly interrupted by the strike early on – with the paper seeing its employees leave their positions – it quickly resumed operations. The newspaper referred to itself as a “POLITICAL VICTIM of the Soviet government” as a result of its “forced suspension” during the strike (Manitoba Free Press, May 22, 1919).

Its editor at the time, John W. Dafoe, was not wholly anti-labour, but was against the strike. The newspaper reported on the strike throughout the events of May-June 1919, and was generally biased against labour, the strike, and immigrants. While Dafoe supported these views, he did not believe the leaders of the Strike should have been charged and incarcerated, but only because he believed their arrest would turn them into martyrs and support the cause of extremists. Overall, the newspaper followed the rhetoric of many anti-strike papers, emphasizing the role of Bolshevists and enemy aliens in the conflict.

Western Labor News

Western Labor News was published by the Winnipeg Trades and Labor Council, which called the strike. Its first issue was published on August 2, 1918, when the paper replaced The Voice, a previous publication by the WTLC. At the start of the strike, special editions were released to keep strikers up to date on events and developments. One of few pro-strike newspapers, Western Labor News sought to fight against the “half-truths” and “half-suppressed […] real facts” appearing in other newspapers in Winnipeg (Western Labor News, May 19, 1919).

While the paper had a strong leftist leaning, it appeared to moderate its language once the strike was called, as it sought to calm its readers, fearing that if its rhetoric was too strong, it may incite violence and ultimately undermine the strike. Referring in particular to the Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand, many articles in the Western Labor News asked their readers not to “play their game. Keep out of their trap. Keep quiet”, as they knew any rioting, no matter the cause, would look poorly on the strikers and believed that the Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand would take advantage of this (Western Labor News, May 22, 1919).

These fears proved to be justified, as many men who staffed the paper were targeted on multiple occasions. William Ivens, Western Labor News’ editor, was arrested on June 17, alongside the paper’s advertising manager, Alderman John Queen. J.S. Woodsworth briefly stepped in as editor following the arrests, but on June 23, the Winnipeg Print and Engraving Co., who published Western Labor News, was served with a letter from A.J. Andrews requesting that they cease publication of the newspaper. J.S. Woodsworth was arrested later that day and Fred Dixon, who witnessed the arrest, succeeded him as editor. As a result of the publication ban, Dixon published the paper under different titles, including The Enlightener and the Western Star, but only managed to hold onto the position for a few days, until his arrest on June 27. For their roles as editors, both Dixon and Woodsworth would be charged with seditious libel. The latter was acquitted, while the charges were dropped for the former. Ivens was later charged with and found guilty of seditious conspiracy and of committing a common nuisance. In the aftermath of the strike and the trials, the paper continued to publish. Its final issue was printed on April 13, 1923.

For more information on Western Labor News and its publishers, see Who: Strike Leaders

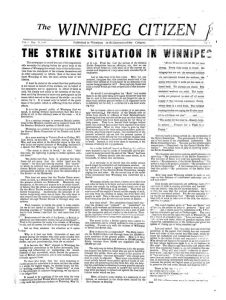

The Winnipeg Citizen

The Winnipeg Citizen was a daily newspaper first published by the Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand on May 19, 1919 and distributed in part through many Winnipeg fire halls and churches. While the paper claimed to be the source of “the actual facts of the strike”, it presented a clear bias in its anti-strike view, as well as a hostile tone towards immigrants (Winnipeg Citizen, May 19, 1919). The Winnipeg Citizen referred to the Strike Committee as Soviet dictators who organized not a strike, but a revolution meant to overthrow the government and British institutions.

The Winnipeg Citizen was a daily newspaper first published by the Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand on May 19, 1919 and distributed in part through many Winnipeg fire halls and churches. While the paper claimed to be the source of “the actual facts of the strike”, it presented a clear bias in its anti-strike view, as well as a hostile tone towards immigrants (Winnipeg Citizen, May 19, 1919). The Winnipeg Citizen referred to the Strike Committee as Soviet dictators who organized not a strike, but a revolution meant to overthrow the government and British institutions.

The Winnipeg Citizen further played on emotion – reminding Winnipeggers that the strike would result in the stoppage of milk and bread deliveries, and possibly of emergency services provided by doctors, firemen and policemen, to the detriment of children and other vulnerable Winnipeggers, further stating that the Strike Committee was starving the workers it claimed to serve (Winnipeg Citizen, May 21, 1919). It placed itself as a paper representing all citizens of Winnipeg, stating in one issue that “The Winnipeg Citizen is Your Paper” (Winnipeg Citizen, May 21, 1919).

In reality, however, the Winnipeg Citizen‘s authors were wealthy professionals who were out of touch with many issues facing the working class. During an address about the strike, known Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand member Isaac Pitblado listed the inconveniences of the strike, mentioning starving children only after complaining about having to take the stairs to his office while the elevator operators were on strike. In truth, the paper was published to rally Winnipeggers and spread anti-strike sentiments more broadly to preserve the status quo.

Though it presented itself as a reliable source – one interested in the facts – the Winnipeg Citizen was careful not to identify its writers. Its editors and authors were not advertised in the paper, unlike other newspapers in Winnipeg, which advertised this information publicly. Only following the strike was it known that the Winnipeg Citizens’ editors were Travers Sweatman and Fletcher Sparling. Otherwise, much like the Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand, many of the people behind the Winnipeg Citizen remain shrouded in obscurity.

Image Source: First edition of the Winnipeg Citizen. Winnipeg Citizen, May 19, 1919. UML.

For more information on the Winnipeg Citizen and its publishers, see Who: Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand

The Winnipeg Telegram

The Winnipeg Telegram was first published as the Daily Nor’Wester in 1894. In 1907, it was renamed as the Winnipeg Telegram. During the strike, the Winnipeg Telegram operated from the corner of Albert Street and McDermot Avenue, on Newspaper Row. While, like most local dailies, the Winnipeg Telegram was anti-strike, it was much more blatantly biased in its reporting of the events of 1919, often tapping into red scare and enemy alien fears that existed amongst the public. One issue of Western Labor News stated that the “Telegram may be an authority on rattlesnakes – but it is no defender either of law, order or the British Constitution” (Western Labor News, June 4, 1919).

A neutral tone was rarely adopted. The arrest of the strike leaders was mocked as “reds…enjoying a well-earned rest at Stoney [sic] Mountain” (Winnipeg Telegram, 1919-06-17). The James Street Labor Temple became the “proletariat dictatorship of the James street Soviet” (Winnipeg Telegram June 4, 1919). Shortly following the strike, in 1920, the Winnipeg Telegram ceased to publish, following a merger with the Winnipeg Tribune.

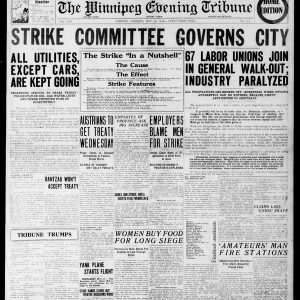

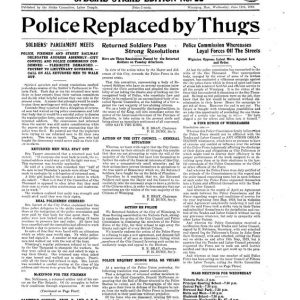

The Winnipeg Tribune

The Winnipeg Tribune was first published in 1890, after the Winnipeg Sun was bought out by D.L. McIntyre and L.R. Richardson. When the strike broke out, the Winnipeg Tribune, which operated from Newspaper Row, found its publication to be interrupted as a result of the strike, and consequently, no issues ran between May 16 and May 23 inclusively. When publication resumed, the Winnipeg Tribune placed itself as a news source which upheld the principles of neutrality, stating in multiple issues that it had a policy of “STRICT FAIRNESS” and a commitment to reporting “BOTH sides” of the story (Winnipeg Tribune, May 24, 1919). In later publications, this statement was altered to specify that it did “not mean that this newspaper is neutral. It means simply that it regards its news as a public utility” (Winnipeg Tribune, May 31, 1919). During the strike trials, to ensure both sides were told, the Winnipeg Tribune further published the full opening statements of both the prosecution and defense lawyers to provide a balanced account of the court proceedings.

While not as obvious as other news sources, the Winnipeg Tribune still presented some biases in its articles, integrating anti-Bolshevik and anti-alien rhetoric into its articles and further publishing anti-strike advertisements by the Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand throughout the duration of the strike.

After the strike, the Winnipeg Tribune merged with the Winnipeg Telegram and continued to publish under the Winnipeg Tribune title until the paper ceased to publish in 1980.