Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand

The Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand was a cabal of Winnipeg’s business and professional elite who opposed the General Strike and actively worked to break it. To accomplish this, the Citizens’ Committee used its resources, influence, and political savvy to ensure the authorities dealt with the strike in a way that benefited its members. The membership of the Citizens’ Committee was secret. Only a handful of members publicly identified themselves during the strike for the purpose of negotiations and communicating the Committee’s will. Even today, 100 years later, the number or extent of its membership is unknown. Only a few dozen members have been confirmed, all from its executive.

Photographs of what is believed to be a banquet attended by members of the Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand following the strike. WCPI A1292-38698-99. UWA.

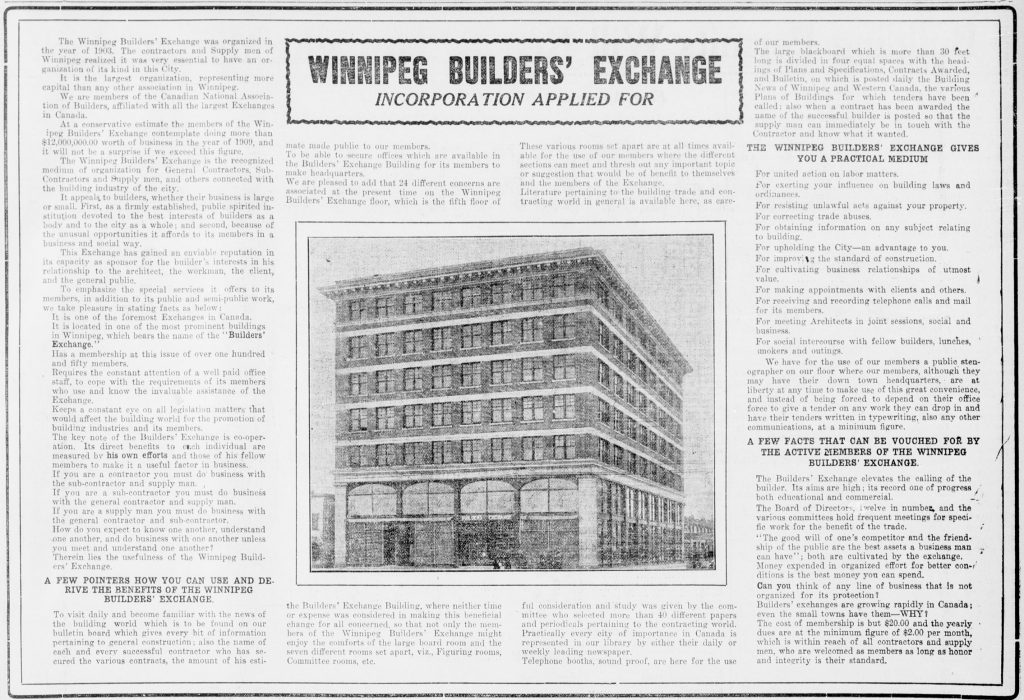

The Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand was one of several organizations of business and professional elite that had begun to form in the early 20th century to counter labour unionism. One such organization, the Minneapolis-based Citizens’ Alliance, had the most direct influence on the Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand. The Citizens’ Alliance was formed by a conglomerate of business owners and those opposed to unionism in Minneapolis in 1903. They pooled their resources and used everything from litigation to spy-craft to suppress workers and unionism. Its policy when dealing with labour was to “cut off all negotiations and accept nothing but unconditional surrender” (Kramer and Mitchell 2010, 47). This fanaticism appealed to many of Winnipeg’s business elite and, in July 1917, the Winnipeg Builders’ Exchange invited the Citizens’ Alliance to the Royal Alexandra Hotel to discuss the creation of a Winnipeg chapter, which became official in September in a meeting at the home of future Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand member Ed Parnell.

The following year, City employees led a strike that very nearly became a general strike. To stop it, Winnipeg business owners and professionals met at the Royal Alexandra once again. This time, however, they formed the Citizens’ Committee of One Hundred, which unlike the Citizens’ Alliance, took a more conciliatory approach towards the striking civic employees. Its membership was more diverse, including women and those outside the business elite, all of whom added up to exactly 100. Nonetheless, many of its members would also serve on the Committee of One Thousand the following year, including A.L. Crossin, who chaired both. The Committee of One Hundred staffed vacant City positions, but also helped broach a settlement between the City and its employers.

It is unknown exactly when the Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand formed, but it was well established at least two days before the General Strike began. It consisted of an executive, chaired by A.K. Godfrey, and a General Committee, chaired by A.L. Crossin, the extent of which is unknown. It also had various sub-committees that carried on day-to-day operations, such as the sub-committee responsible for the volunteer fire department. Organizing volunteers to replace striking workers was one of the Citizen’s chief activities, as was helping to continue City services that the strike had cut off. Its members were genuinely afraid that the strike represented the start of a Bolshevik uprising and did everything in their power to break it. The Committee ran an anonymous newspaper, the Winnipeg Citizen, which proliferated propaganda to discredit the strike and its leaders. The Citizens’ were particularly fond of fanning anti-immigrant sentiments and appealing to British nationalism, a tactic which appealed to many, including many returned soldiers. Throughout the strike, the Citizens attended meetings meant to settle the strike, but they adopted the Citizens’ Alliance method of accepting no compromise and did all they could to sabotage the negotiations.

As Winnipeg’s elite, the Citizens wielded significant influence over local and Federal authorities, which they used to their advantage. This was particularly true of A.J. Andrews, who became an ally of Acting Federal Minister of Justice Arthur Meighen, an alliance which Andrews and the Citizens used to amend Federal immigration legislation, orchestrate the arrests of several strike leaders on June 17, and shut down the Western Labor News a few days later. A.J. Andrews and several other lawyers among the Citizens’ ranks prosecuted the arrested strike leaders, despite the obvious conflict of interest. For their work, the lawyers received approximately $227,000 between them (Kramer and Mitchell 2010, 291). By comparison, the Prime Minister made $15,000 in 1920. The Federal Government had difficulty finding money to cover the costs, but eventually decided to use funds that were supposed to have been earmarked to help demobilize soldiers returning from the First World War.

The Citizens’ Committee disbanded after the strike ended – at least in appearance. Many of its members reorganized into two organizations: the Citizens’ League and the Employers’ Association. The former was formed in August 1920 in order to carry on the work the Committee of One Thousand attributed to itself: upholding British law and constitutional order against threats such as Bolshevism. While it had a slightly more diverse membership, former Committee of One Thousand members occupied many of its executive positions. The other organization created, the Employers’ Association, was, as the name suggests, meant to look out for the interests of employers and business. It was founded in January 1920 and at least eight former Citizens sat on its board of directors, as did several of the Citizens’ allies during the strike (Kramer and Mitchell 2010, 319).

Prominent Members of the Citizens' Committee of One Thousand

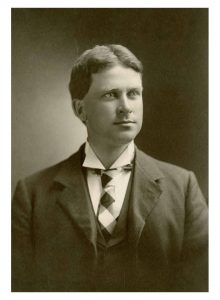

Alfred Joseph Andrews was born in 1865 in Franklin, Quebec. His father was a Methodist Minister who struggled to support his family, but instilled in Andrews a penchant for rhetoric, offering up a cent anytime Andrews or one of his five siblings caught their father in a mispronunciation (Kramer and Mitchell 2010, 40). In 1880, Andrews left his home for Winnipeg, where he began to study law at his older brother’s firm – that of Manitoba attorney General D.M. Walker – but left briefly to fight against Louis Riel in the 1885 Northwest Rebellion. Andrews was 21 years old when he was called to the Manitoba Bar. In addition to practicing law, Andrews dabbled in land speculation and entered civic politics in 1893 as a City Alderman for Ward 2. In 1898, the 32 year-old Andrews became Winnipeg’s 19th mayor. Due to his age and youthful appearance, Andrews earned the nickname “the boy mayor”. Having conquered City Hall, Andrews set his sights on the Manitoba Legislature, running unsuccessfully as a Conservative candidate in 1899, 1910, and 1914 (the latter was lost to Fred Dixon). He was a member of several elite Winnipeg social clubs, including the Manitoba Club and the St. Charles Country Club.

During the the strike, Andrews was the most influential member of the Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand and its de facto leader. Though he had no official state authority and was not in any leadership position, he was, as described by William R. Plewman, who reported on the strike for the Toronto Star “the principal human factor in opposing the strike movement…He was here, there and everywhere, directing the operations of the Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand…no one person had more to do with these various moves than had Mr. Andrews” and decisions were only made “after Andrews had voiced his approval” (Dupuis 2014, 125). He accomplished this largely through his ability to manipulate the state and those who were in positions of authority.

This was particularly true of Acting Federal Minister of Justice Arthur Meighen, whom Andrews wielded consider influence over. On May 21 1919, Andrews and a small delegation of the Citizens arrived in Fort William (now Thunder Bay) to intercept Meighen and Minister of Labor Gideon Robertson, who were on their way from Ottawa to Winnipeg to assess the strike situation. Andrews was able to convince Meighen of his take on the situation and Meighen, in turn, appointed Andrews as a representative of the Justice Department in Winnipeg, an ambiguous title that Andrews interpreted broadly (Kramer and Mitchell 2010, 100-101). The two continued to correspond throughout the strike, with Andrews feeding Meighen his take on how it was unfolding and what had to be done to stop it. Andrews’ influence over Meighen was such that he was able to legislate through him. Andrews convinced Meighen to amend the Immigration Act to allow for the deportation of any non-Canadian citizen who engaged in sedition. When Meighen’s first amendment wasn’t satisfactory to Andrews because it didn’t allow for the deportation British immigrants, Andrews convinced him to amend it again. The second amendment took only one hour to pass through Parliament. He did the same at the municipal level, bringing motions before City Council through an Alderman he held sway over, such as J.K. Sparling.

The lack of clarity in Andrews’ position allowed him to slightly alter the scope of his powers depending on who he was dealing with. This ambiguity allowed him to orchestrate the arrests of several strike leaders on June 17 and shut down the Western Labour News not long after. Prior to the June 17 arrests, Andrews and others of the Citizens met with Provincial prosecutors, Minister Robertson, and others to determine which of the strike leaders would be arrested. Furthermore, he used his influence and tactical acumen to determine almost every aspect of the subsequent trials. He chose which of the arrested would be tried under the new Immigration Act and which would be tried under the Criminal Code; he had a hand in the selection of the judges and officials overseeing the trials; he hired a private detective agency to thoroughly investigate every possible juror to stack the jury in favour of the prosecution; and he prosecuted the accused himself.

Andrews’ arguments in court frequently spoke to ideals of morality, love of one’s country, veterans’ sacrifices, religion, and British pride. His closing address to the jury for R.B. Russell’s trial clocked in at nearly 6 hours. His legal services were paid for by the Federal Government, out of funds that were intended to be used to help returning veterans adjust to civilian life. In total, for his work orchestrating the arrests of the strike leaders and their prosecution, Andrews was paid over $47,000. This was over three times what the Prime Minister made in 1920 (Kramer and Mitchell 2010, 291).

After the strike, Andrews was the President of the Law Society of Manitoba from 1922-1925 and received accolades and awards for his successful career. His firm was inherited by Aikens, MacAuley, and Thorvaldson LLP. He died on January 31, 1950 and was buried in St. John’s Cathedral Cemetery.

Image Source: COWA. Photograph Collection (P1 File 42).

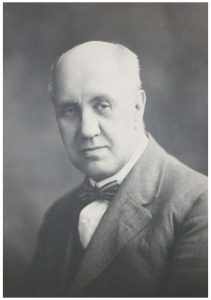

James Bowes Coyne was born on August 24, 1878 in St. Thomas, Ontario. He went to Upper Canada College and the University of Toronto, and studied law at Osgoode Hall. He was called to the Ontario Bar in 1904 and was called to the Manitoba Bar the following year when he moved to Winnipeg and became a partner at the Winnipeg firm Aikins, Robson, Fullerton, and Coyne (by 1919, the firm’s name was “Coyne, McVicar, and Martin”). In Winnipeg, Coyne – or “Bogus”, as he we nicknamed – had a successful law career: he was made King’s Counsel in 1916 and, that same year, became a Bencher for the Law Society of Manitoba (a position he held until 1925). Coyne was also a member of Winnipeg social elite – he was a member of both the Carleton Club and the Manitoba Club. Politically, Coyne was a Liberal.

James Bowes Coyne was born on August 24, 1878 in St. Thomas, Ontario. He went to Upper Canada College and the University of Toronto, and studied law at Osgoode Hall. He was called to the Ontario Bar in 1904 and was called to the Manitoba Bar the following year when he moved to Winnipeg and became a partner at the Winnipeg firm Aikins, Robson, Fullerton, and Coyne (by 1919, the firm’s name was “Coyne, McVicar, and Martin”). In Winnipeg, Coyne – or “Bogus”, as he we nicknamed – had a successful law career: he was made King’s Counsel in 1916 and, that same year, became a Bencher for the Law Society of Manitoba (a position he held until 1925). Coyne was also a member of Winnipeg social elite – he was a member of both the Carleton Club and the Manitoba Club. Politically, Coyne was a Liberal.

During the civic employees strike of 1918, Coyne was a member of the Citizens’ Committee of One Hundred and was part of the ad-hoc committee that drafted its inaugural resolutions. Though the Citizens’ Committee of One Hundred took a relatively conciliatory stance towards organized labour, Coyne himself was far less conciliatory when the Winnipeg Policemen’s Union joined the Trades and Labor Council later that year. In an October 31 letter to the Board of Trade, Coyne described the Winnipeg Trades and Labor Council as being run by “acknowledged Bolsheviki” who wanted to overthrow constituted authority, and decried the union’s affiliation with the Trades and Labor Council as “the inauguration of anarchy” (Kramer and Mitchell 2010, 57). During the General Strike, Coyne was a member of the Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand, to which he lent his legal prowess, becoming one of A.J. Andrews’ closest advisors (Kramer and Mitchell 2010, 101). It is likely that Coyne was part of the Citizens’ Committee delegation that met with Acting Minister of Justice Arthur Meighen and Minister of Labour Gideon Robertson in Fort William on May 21, 1919 (Kramer and Mitchel 2010, 57).

He was one of several Citizens who helped orchestrate the arrests of several strike leaders on June 17 and acted as one of the prosecutors in the trials that followed. During the preliminary hearings, Coyne began to read select passages from the Communist Manifesto, copies of which were found in the raid of the James Street Labor Temple. Defence attorney McMurray objected that if he was going to read select passages, he should read them all, otherwise he should read none. The judge disagreed and Coyne read off several passages he believed to be damning. In defence, McMurray noted that the Communist Manifesto was in libraries across the world, to which Coyne replied “you might apply that to the bacteria in a laboratory” (Kramer and Mitchell 2010, 252). For his legal services, Coyne benefited from an arrangement A.J. Andrews had made with the Federal Government in which Andrews and the other Citizens’ Committee laywers, Coyne included, were paid out of Federal funds earmarked to help veterans demobilize. Not only were they paid for the trials themselves, but for the work of Andrews (and by extension, Coyne) leading up to the strike leaders’ arrests. In total, Coyne was paid $28,996. At the time, the Prime Minister of Canada made approximately $15,000 a year.

In 1922, Coyne’s legal fees would once again be the subject of controversy when his bill to the Provincial Government for services rendered during the Legislative Building scandal amounted to $29,237, an unreasonable bill for the government to agree to, according to Fred Dixon and William Ivens, whom were both Members of the Legislative Assembly at the time. Coyne’s career culminated in an appointment as a judge in the Manitoba Court of Appeal in 1946. He died in Ottawa on June 16, 1965. His son, James Elliott Coyne, went on to become the Governor of the Bank of Canada before being fired by Prime Minister Diefenbaker in what was known as the Coyne Affair.

Image Source: Winnipeg Tribune, February 23, 1929. UML.

Albert Livingstone Crossin was born in 1868 in Waterloo, Ontario. He was a Chartered Accountant who worked for various firms and businesses throughout his life. In London, Ontario, he was employed by Huron and Erie Mortgage Co. Ltd. Later, he moved to Toronto to work for Toronto General Trusts Corp. and it was through this job that Crossin came to Winnipeg, as he was tasked with opening its Winnipeg branch. By the time of the 1919 General Strike, Crossin worked as an investment manager for Oldfield, Kirby, and Gardner. He was active in the Winnipeg business community, serving as President of the Winnipeg Chamber of Commerce from 1916-1917 and as President of the Board of Trade. He was also a member of various elite social organizations, including the Manitoba Club and the Canadian Club, and he was an active Freemason, serving as Grand Master of the Grand Lodge of Manitoba in 1925. He also served as Vice Chairman of the Victory Loan Campaign and identified politically as a Liberal.

Albert Livingstone Crossin was born in 1868 in Waterloo, Ontario. He was a Chartered Accountant who worked for various firms and businesses throughout his life. In London, Ontario, he was employed by Huron and Erie Mortgage Co. Ltd. Later, he moved to Toronto to work for Toronto General Trusts Corp. and it was through this job that Crossin came to Winnipeg, as he was tasked with opening its Winnipeg branch. By the time of the 1919 General Strike, Crossin worked as an investment manager for Oldfield, Kirby, and Gardner. He was active in the Winnipeg business community, serving as President of the Winnipeg Chamber of Commerce from 1916-1917 and as President of the Board of Trade. He was also a member of various elite social organizations, including the Manitoba Club and the Canadian Club, and he was an active Freemason, serving as Grand Master of the Grand Lodge of Manitoba in 1925. He also served as Vice Chairman of the Victory Loan Campaign and identified politically as a Liberal.

During the Winnipeg civic employee strike of 1918, Crossin was a member of the Citizens’ Committee of One Hundred. He was part of the committee that drafted the organization’s resolutions, was made its chairman, and was a member of its Conciliation Sub-committee, which attempted to negotiate an end to the strike (Johnson 1978, 145-148). During the General Strike, Crossin reprised his role of chairman, this time of the Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand’s General Committee. This made him one of the Citizens’ Committee’s few public faces. He attended several meetings and negotiations with government authorities over the course of the strike, in which he spoke for the Citizens and made their will known. On occasion, this meant speaking directly to the public, including strikers and those who sympathized with them. At one meeting, according to the Winnipeg Citizen, Crossin attempted to explain to a crowd of strikers why the Citizens’ Committee’s was formed, and was met by jeers, boos, and sarcastic responses. He then began to tell the crowd that he was born in a log cabin in Ontario, to which the angry crowd replied, “you ought to go back” (Winnipeg Citizen, May 23, 1919). In his public statements, Crossin sometimes downplayed the strength and resolve of the strikers, claiming that 85 percent would return to work if the police could provide adequate protection (Manitoba Free Press, June 6, 1919). On other occasions, he echoed the apocalyptic language of many of the Citizens: when pro-strike returned soldiers marched down Wellington Crescent on June 4, Crossin painted it as a virtual invasion, claiming that the marchers “only needed weapons to become an army” (Kramer and Mitchell 2010, 109). He was adamant that, rather than a Provincial commission to investigate the causes of the strike, a Canada wide commission was needed to expose Bolshevism; he received a letter from Acting Minister of Justice Arthur Meighen on the subject and attempted to rally the Citizens to press him and the Federal government for such a commission. Only a national commission, he claimed, could “expose the whole damnable conspiracy.” and that such exposure was “imperative if we are to have industrial peace” (Kramer and Mitchell 2010, 209).

After the strike had ended, Crossin continued to have a successful career. In 1938, he was the founding executive director of the Manitoba Hospital Service Association, which later became Manitoba Blue Cross. Crossin finally retired in 1952, but held a position as a member of the Winnipeg Advisory Board of the Huron and Erie Mortgage Co. until his death on October 19, 1956. He was buried in St. John’s Cemetery.

Image Source: Winnipeg Tribune, March 21, 1934. UML.

Alvin Keyes Godfrey was born in St. Louis, Missouri on January 30, 1871. Though he earned a Bachelor of Laws degree from the University of Minnesota in 1897, Godfrey was a business man. In Minneapolis, he worked for the Peavey Grain Company and, in 1902, he came to Winnipeg to form the Canadian Elevator Company and, later, the Monarch Lumber Company, the latter of which he served as the Chairman, General Manager, and President. He held various positions in the Winnipeg business community, including President of the Winnipeg Grain Exchange from 1913-1914 and of the Board of Trade from 1917-1918. He was also active as a member of Winnipeg’s social elite; he was a member of the Manitoba Club and the Canadian Club, a Mason, and was a founder of the St. Charles Country Club.

Alvin Keyes Godfrey was born in St. Louis, Missouri on January 30, 1871. Though he earned a Bachelor of Laws degree from the University of Minnesota in 1897, Godfrey was a business man. In Minneapolis, he worked for the Peavey Grain Company and, in 1902, he came to Winnipeg to form the Canadian Elevator Company and, later, the Monarch Lumber Company, the latter of which he served as the Chairman, General Manager, and President. He held various positions in the Winnipeg business community, including President of the Winnipeg Grain Exchange from 1913-1914 and of the Board of Trade from 1917-1918. He was also active as a member of Winnipeg’s social elite; he was a member of the Manitoba Club and the Canadian Club, a Mason, and was a founder of the St. Charles Country Club.

Godfrey was a member of the Citizens’ Committee of One Hundred in 1918, which was tasked with negotiating a settlement between the City of Winnipeg and striking civic employees. However, while negotiating in public, in private, Godfrey sent letters to the Federal Government, imploring it to intervene and put a stop to the strike (Kramer and Mitchell 2010, 48-49). During the General Strike, Godfrey sat as Chairman of the Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand’s executive. Since the beginning of the strike, the Citizens’ had attempted to install a private police force to replace the City police who were sympathetic to the strike. To further this end, Godfrey, along with fellow Citizens Travers Sweatman and W.R. Ingram met with Aldermen J.K. Sparling, Chair of the Police Commission, and worked towards the creation of the Special Police force. However, when Sparling issued the Slave Pact ultimatum to Winnipeg police at the end of May – without consulting the Citizens’ Committee – Godfrey was furious and publicly berated Sparling for his transgression (Kramer and Mitchell 2010, 113). Godfrey, along with several others of the Citizens, was involved in determining which of the strike leaders would be arrested on June 17, and when the strike was nearing its end, and the idea of a commission to investigate the strike was being considered by the Province, Godfrey was one of the Citizens clamouring to have the commission investigate Bolshevism in Canada and the One Big Union instead.

After the strike ended, Godfrey became First Vice-President of the Citizens’ League and sat as a board member of the Employer’s Association of Manitoba. He died on July 4, 1956 and was buried in Minneapolis.

Image Source: Winnipeg Tribune, May 10, 1916. UML.

Edward Parnell was born in Dover, England in 1859. He came to Canada while still a boy, settling in London, Ontario where he eventually opened a bakery and served as Alderman for 11 years. Parnell came to Winnipeg in 1909, settled on Wolseley Avenue, and partnered with J.T. Speirs to open the Speirs-Parnell Baking Company on Elgin Avenue. This company became the largest bakery in Winnipeg, employing 120 people.

Parnell was also active in the wider business community. He was affiliated with numerous business associations and alliances, was the Chairman of the Winnipeg Manufacturers Association from 1918-1919, and was a member of the Manitoba Club. In 1917, Parnell became President of the recently formed Winnipeg Citizens’ Alliance, which was known for its heavy-handed approach to dealing with labour. During the 1918 civic employees strike, Parnell was a member of the Citizens’ Committee of One Hundred, negotiating with the strikers on the one hand while on the other, as President of the Citizens’ Alliance, writing letters to the Federal government in an attempt to stop the strike through legislation.

When the General Strike broke out on May 15, 1919, Parnell was a member of the Executive of the Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand and worked with its other members to break the strike. As the owner of the largest bakery in Winnipeg, Parnell was especially vocal in his critique of the strikers after bakers walked off the job on June 4, an act he and the Winnipeg Citizen decried as “child murder”. As the representative for City bakeries and bread makers, Parnell met with the Special Food Committee on June 5 and demanded increased police protection for bakeries supplying the City. After the events of Bloody Saturday, Parnell telegrammed Acting Justice Minister Arthur Meighen and congratulated him on the stern action taken by the Mounted Police that day.

After the strike, Parnell continued to have a successful career. He was on the Executive of the Citizens’ Alliance, was President of the Board of Trade from 1920 to 1921, a board member of the Employers’ Association, served on the Founding Advisory Board to the Winnipeg Foundation, and, from 1920 until his death in 1922, was Mayor of Winnipeg. He died in Victoria during a leave of absence from his Mayoral duties.

Image Source: COWA. Art Collection (A01068).

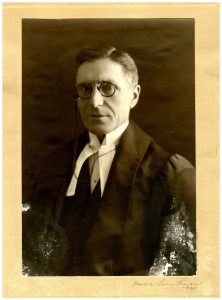

Born in Glenelg, Nova Scotia on March 15, 1867, Isaac Pitblado moved to Winnipeg with his family in 1881 when his father, Reverend Charles Bruce Pitblado, took a position at St. Andrew’s Church. Shortly after their arrival, Pitblado went to Manitoba College to continue the studies he began at Dalhousie University prior to the family’s move. There, he completed a Bachelor of Arts in Classics in 1886 and began articling for the law firm of Aikins, Culver, and Company. In 1889, Pitblado obtained a Bachelor of Laws from the University of Manitoba. In 1890, he was called to the Bar, and three years later, in 1893, completed his Master’s of Arts. The same year, he was appointed registrar at the University of Manitoba (a position which he held until 1900), and became a partner at the firm Pitblado and Hoskin. From 1917 to 1924, Pitblado was the first Chairman of the Board of Governors at the University of Manitoba. In 1918, Pitblado was a member of the Citizens’ Committee of One Hundred, which helped mediate a settlement between the City of Winnipeg and its striking employees.

Leading up to the General Strike, Pitblado was appointed a representative for employers on the Street Railway Arbitration Board. An unspecified health issue kept him from returning to Winnipeg from Missouri in early May, which caused him to miss several Arbitration Board meetings. His prolonged absence increased tensions with the street railway workers, who were led to believe that their employers would expedite the arbitration process in order to resolve the matter quickly.

During the strike, Pitblado was a prominent member of the Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand. He was already well acquainted with many of its other members – he had previously worked for A.J. Andrews (whom he had nominated for mayor in 1898), employed Travers Sweatman, and socialized with many Citizens as a member of the Manitoba Club. Pitblado often acted as a spokesperson for the Committee, speaking publicly about the strike across Canada, including in Moose Jaw and Halifax. On May 21, Pitblado accompanied other Committee members to Fort William (now Thunder Bay) to intercept Acting Minister of Justice Arthur Meighen and Minister of Labour Gideon Robertson on their way to Winnipeg from Ottawa. The Citizens’ sought to gain the ministers’ support by convincing them of the Citizens’ take on the strike. Pitblado already knew Meighen professionally, as he had provided legal advice to him on multiple occasions. One of the Citizens’ primary functions was providing volunteers to staff positions left vacant by the strike. Returned soldier Edward Pitblado, Isaac’s son, was one such volunteer, working as a firefighter during the strike. Pitblado was one of several Citizens who had a hand in choosing which of the strike leaders would be arrested on June 17. He also helped in their prosecution, earning thousands of dollars from Federal funds that were earmarked for demobilizing veterans.

Once the trials had ended, Pitblado rarely spoke about the strike publicly. He served as the president of the Canadian Bar Association from 1934 to 1935 and continued to practice law well into his nineties, finally passing away at the Winnipeg General Hospital on December 6, 1964. He is buried in the Elmwood Cemetery.

Image Source: Pitblado Family fonds. UMASC.

Note: The photograph of Isaac Pitblado is signed by fellow Citizen’s Committee member Travers Sweatman. As Sweatman was an amateur photographer, it is likely that he took this photograph.

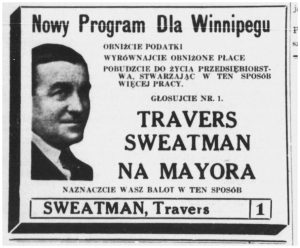

Travers Sweatman was born in Prembroke, Ontario on October 27, 1879 to Anglican parents, William P. Sweatman and Elizabeth L. Sweatman (née Angus). Sweatman arrived in Winnipeg sometime prior to 1900 when he obtained his Bachelor of Arts degree from St. John’s College, followed shortly afterwards by a Master of Arts from the University of Manitoba in 1904. Sweatman articled from 1903 to 1906, where he worked for Isaac Pitblado, a fellow future Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand member. In 1906, Sweatman was called to the bar. From 1906-1912, Sweatman worked as a lawyer for the Canadian Northern Railways, marrying Constance Winifred Newton in 1910. Together they had four children. From 1912 to 1940, Sweatman was a partner at the law firm of Richards, Sweatman, Kemp, and Fillmore.

During the General Strike, Sweatman was a member of the Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand. He co-edited the Citizens’ newspaper, the Winnipeg Citizen, alongside Fletcher Sparling. On May 21, he accompanied other committee members to Fort William (now Thunder Bay) in order to reach Acting Minister of Justice Arthur Meighen and Minister of Labour Gideon Robertson prior to their arrival in Winnipeg. They sought to gain the allegiance of the ministers by convincing them of the Citizens’ take on the strike.

Though the membership of the Committee was never publicized, Sweatman’s membership was made public by fellow Citizen Ed Parnell’s testimony during the strike trials in 1920. This was a clear conflict of interest, as Sweatman, along with Pitblado and A.J. Andrews, were the prosecutors in these trials and had orchestrated the arrests of the strike leaders on June 17, 1919. Despite this, Sweatman and the other prosecutors succeeded in obtaining a guilty verdict for most of the strike leaders, but Sweatman went further and advocated for the deportation of the leaders of the One Big Union.

Following the strike, Sweatman became the president of the Board of Trade – a position he maintained from 1921-1925. He was also a member of the Manitoba Club, St. Charles Country Club, and the Winnipeg Winter Club, where he also served as president. Despite spending most of his life working in business and law, Sweatman was also described as an artist due to his interest in photography and the classics. In 1938, he ran an unsuccessful campaign for mayor and was defeated by John Queen, whom Sweatman had helped send to jail in 1919. Sweatman moved to Toronto in 1940 to practice law, but died suddenly the following year.

Image Source: Advertisement for Sweatman’s mayoral race. Czas, November 22, 1938. UML.

Other Known Members of the Citizens' Committee of One Thousand

F.W. Adams

H.M. Agnew

Ed Anderson

A.L. Bond

John E. Botterell

N. J. Breen

George Carpenter

M.F. Christie

D.A. Clark

D.J. Dyson

C.C. Ferguson

W.M. Governlock

George Guy

W.R. Ingram

G.N. Jackson

F. Luke

W.A. Mackay

C.O. Markle

W. McWilliams

Robert McKay

George Munro

C.A. Richardson

Flether Sparling

A.B. Stovel

H.M. Tucker

J.C. Waugh

Esten Kenneth Williams

W.P. Riley

C.D. Sheppard

Allies of the Citizens' Committee of One Thousand

The Builders' Exchange

The Builders’ Exchange was founded in 1903 to advocate on behalf of contractors and suppliers, to monitor legislation that would affect builders’ interests, to self-regulate the industry, and to provide a united front in labor disputes (Winnipeg Tribune, June 6, 1909). In 1909, the Builders’ Exchange was the largest organization representing capital in Winnipeg, its 150 members estimated to have conducted over $12,000,000 in business that year (Winnipeg Tribune, June 6, 1909). Its headquarters – the Builders’ Exchange Building, located at the northwest corner of Portage Avenue and Hargrave Street, functioned as a space for conducting business, networking, and generally socializing with peers. In July 1917, the Builders’ Exchange invited the Minneapolis Citizens’ Alliance and a host of Winnipeg businessmen to a dinner at the Royal Alexandra Hotel. This led to the creation of the Winnipeg’s Citizens’ Alliance, a precursor to the Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand.

One of the benefits of such an all-encompassing organization was its ability to support its members in disputes with unions and employees. In the event of labour disputes, the Builders’ Exchange could blacklist specific employees, forbid its members from negotiating with specific unions, pool its resources to obtain injunctions and sue for damages, or provide financial support to contractors who were losing money due to work stoppages. It could bargain with unions individually, using a divide and conquer strategy. Despite this, the Exchange had a relatively good relationship with its employees. Prior to the 1913 depression and the First World War, construction was rapid and plentiful, and skilled building trade workers were in high demand. After 1913, however, construction projects dropped dramatically, and Exchange members began to recuperate lost profits by spending less on employees. The situation worsened in February 1919, when the Manitoba Fair Wage Board left the Exchange and its employees to negotiate a new wage schedule privately. As a result, the Building Trades Council, representing almost all workers in the building industry, began negotiating a new wage schedule with the Builders’ Exchange directly, and as singular industrial union rather than as a collection of individual trade unions.

On April 24, the Building Trades Council put forward a wage schedule, asking for an increase in wages of 20 cents for all the workers it represented. The Builders’ Exchange agreed with the Building Trades Council that their current wages were not a living wave, but claimed that bankers would not do business with them if they agreed to the increase, which would prohibit building. They rejected the request and attempted to divide the unions. At an April 28 meeting, some unions were offered 10 cent raises, while others were offered as low as five cents. In addition, if its counter offer was not accepted, the Builders’ Exchange threatened to refuse to negotiate with the Building Trades Council at all and would instead only negotiate with individual unions. The Building Trades Council refused and voted to strike on April 30, officially walking off the following day, May 1.

There were several attempts by Mayor Gray and Premier Norris to broach a settlement between the two sides, both before the start of the General Strike and after, when the Strike Committee and the Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand became involved. The Citizens, however, would only negotiate after the General Strike was called off. The Builders’ Exchange, closely associated with the interests of the Citizens, followed suit and negotiations were stalled. Herbert T. Hazleton, President of the Builders’ Exchange, maintained that he and the Builders’ Exchange were always willing to participate in arbitration and that it was the workers who refused to negotiate, but on several occasions the Builders’ Exchange refused to negotiate until the General Strike had ended and refused to recognize the Building Trades Council (Winnipeg Tribune, June 23, 1919). Though the General Strike ended on June 26, it wasn’t until June 30 that a deal was reached between the Builders’ Exchange and the Building Trades Council. Despite their victory and despite originally claiming they could not afford to, the Exchange gave their employees more than their original counter offer, but the Building Trades Council was not recognized.

Iron Masters

“Iron masters” (sometimes “metal masters”) is a term that referred to the owners and upper management of Winnipeg’s metalwork industry, particularly those of Winnipeg’s largest metal shops: Vulcan Iron Works, Manitoba Bridge and Iron Works, and Dominion Bridge Co. The most prominent figures of these three companies were T.R. Deacon, President and General Manager of Manitoba Bridge and Iron Works, E.G. Barrett, President of Vulcan Iron Works, L.R. Barrett, Vice-President and General Manager of Vulcan Iron Works, and, to a lesser degree, Norman Warren, Western Manager of Dominion Bridge Co. These men were all firmly against unionism and their refusal to recognize and negotiate with the Metal Trades Council was the spark that lit the General Strike. When the strike began, the iron masters realized they had overplayed their hands and decided to negotiate, but this was stymied by the Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand, which convinced the iron masters to cut off all negotiations. To assist in reopening negotiations, the Running Trades Mediation Committee, representing six railway unions, attempted to mediate, as did Federal Minister of Labour, Gideon Robertson. On June 4, the Mediation Committee produced a report that was largely in favour of the Metal Trades Council, but Robertson felt the report was “prejudicial” and convinced the iron masters to agree to a deal in which the Metal Trades Council still would not be recognized (Bumsted 1994, 115). The Strike Committee refused. The dispute between the iron masters and the Metal Trades Council continued after the strike ended on June 26. Despite this, workers began to trickle back into the three foundries and their resistance petered out. The iron masters agreed to a modest reduction in hours, but never recognized the Metal Trades Council.

Edward Gordon Barrett and Leonard Richard Barrett were born in Hamilton on October 6, 1865, and in Windsor on December 12, 1871, respectively, and came to Winnipeg with their family in 1882. Both started their careers at Vulcan Iron Works as low-level employees, Edward as an office boy and Leonard, after working in the fire insurance business, as a clerk. By the time of the General Strike, however, the Barrett brothers ran Vulcan; Edward became President in 1918, succeeding John McKechnie, its founder, and Leonard had become Vice-President and General Manager. Both were active members of Winnipeg’s business elite – Leonard served as the Vice-President of the Board of Trade and the Manufacturers’ Association – and both were staunchly against negotiating with unions. They had no love of fraternizing with their employees and had less love of being challenged by them. In a 1916 dispute, they refused to even meet with a committee of their employees. Of the situation, Leonard said, “This is a free country and…as far as we are concerned the day will never come when we will have to take orders from any union” (Bumsted 1994, 79). They refused to allow unions in their foundry. When the General Strike began, the Barret brothers were forced to consider negotiation, but the Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand convinced them otherwise and they returned to their zero tolerance policy, as stated by Leonard, “the whole situation is in the hands of the Citizens’ Committee…in the meantime, we are going to sit tight and make no concessions” (Mitchell and Kramer 2010, 52). When the Running Trades Mediation Committee and Federal Minister of Labour Gideon Robertson attempted to broach a settlement, Leonard, who was more involved in the negotiations, was described as being “very obdurate and quite unreasonable” and he claimed that “blood would be shed before a settlement was made” (Kramer and Mitchell 2010, 162). Both Barret brothers died unmarried, Edward on January 26, 1935 and Leonard on November 26, 1931.

Image source: L.R. Barrett. Winnipeg Tribune, April 28, 1923. UML.![Thomas Deacon. Source: City of Winnipeg Archives. William Smaill fonds [A2209 file 1].](http://1919strike.lib.umanitoba.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/F0023_0000_0000_A2209_0001_001_p009.jpg)

Thomas Russ Deacon was born on a small farm in Perth, Ontario on January 3, 1865. Deacon’s father died when he was 11, forcing him to put his education on hold and take up work to support his family. He worked as a lumberman in Northern Ontario, becoming foreman of a log drive at a young age, and then went on to work at a sawmill. He continued his education sporadically and saved enough money to attend the University of Toronto, where he earned a degree in civil engineering in 1891. By age thirty, Deacon’s engineering practice was one of the largest in Ontario and made him $7,000 per year (Bercuson 1990, 52). In 1892, Deacon moved to Rat Portage (now Kenora) where he held various positions in the gold and mining industries and became involved in Civic Government. In 1902, Deacon moved to Winnipeg to found Manitoba Bridge and Iron Works alongside Hugh Buxton Lyall. He was also President of the Manitoba Steel and Iron Company and vice-president of the Manitoba Rolling Mill Company. Deacon once again became involved in municipal politics; he was elected Alderman in 1906 and Mayor in 1913 and 1914. In both positions he championed the use of water form Shoal Lake to supply Winnipeg and, as Mayor, he began the process of building the Shoal Lake Aqueduct that isolated the Shoal Lake 40 Reserve. Deacon was heavily involved in Winnipeg’s business community. He was a council member of the Board of Trade, a director of the Industrial Bureau, and an executive member of the Prairie Provinces branch of the Manufacturers’ Association, as well as a member of the Manitoba Club, the Canadian Club, the Southwood Golf Club, and, after the strike, the Employer’s Association.

He was also fiercely anti-labour. He believed in an open-shop policy and consistently refused to recognize or negotiate with unions. He blamed the poor for their own misfortune, once stating that the City’s unemployed should “hit the trail”, and was described in The Voice as having a “contemptible dog-in-the-manger spirit” (Bercuson 1990, 31, 23). In 1917 Deacon resorted to using an injunction and suing for damages to quash a strike. He also hired strike breakers from Montreal. This left a lasting enmity between him and his employees. He died on May 28, 1955.

Image Source: COWA. William Smaill fonds [A2209 file 1].