Racialized Communities

The General Strike was not just about class. Race was also a significant and important factor. Those whose lineages fell outside the British Isles were considered “others” by the British elite who ruled Winnipeg, and were considered dangerous, inferior, or both. Not only were those of “inferior” race marginalized and oppressed, but in many ways their “otherness” began to eclipse class as the main conflict of the strike. Employee and employer became British and others.

"Enemy Aliens"

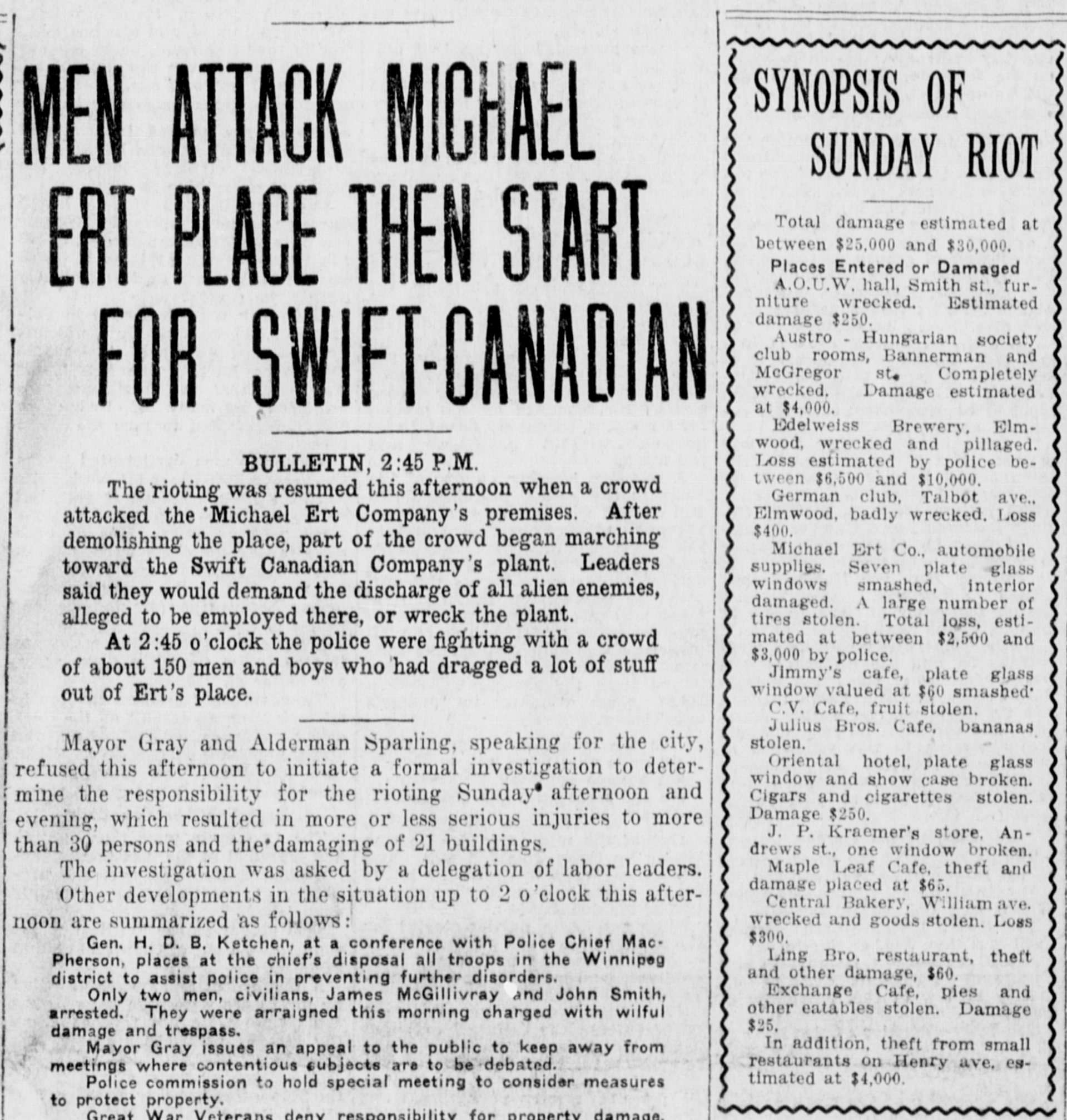

The First World War had created a toxic environment for many Central and Eastern European immigrants in Winnipeg. The start of the war had brought with it the War Measures Act, enacted by the Federal government, allowing them to police immigrants from countries at war with the Commonwealth. Under this act, immigrants from the German and Austro-Hungarian Empires, and, after 1917, Bolshevik controlled Russia, were now “enemy aliens” who could be interned or forced to carry their papers with them for identification. Furthermore, as soldiers returned home from the war, many struggled to find jobs and turned their frustrations to enemy aliens. Many returned soldiers blamed their unemployment on immigrants who, they believed, had taken their jobs while they were away at war. As a result, many immigrant-owned establishments, or businesses that employed so-called enemy aliens became targets of the veterans’ frustrations. In January 1919, riots broke out after veterans overheard socialists in Market Square mourning the deaths two “enemies” – Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg – German socialists. A fight broke out and the veterans gathered 25 “foreigners” and forced them to kiss the Union Jack flag, beating those who refused. The veterans then proceeded to lead demonstrations, one headed north, the other to Elmwood. On their way, they vandalized immigrant-owned businesses, or businesses that they perceived to be sympathetic to enemy aliens.

A group of approximately 150 veterans proceeded to cause between $25,000-$30,000 of damage to 21 buildings, injuring over 30 people in the process. While veterans were clearly the aggressors in this riot, a Tribune article published the following day made it clear that the immigrants victimized by the riots were still not perceived as innocent in the matter: “Mayor Gray, while deploring the acts of hoodlums wrecking windows and shops, said alien enemies in this country ‘have got to keep their mouths shut. I don’t blame returned soldiers a bit for getting after aliens who sympathize openly with an enemy country.’” Such statements made it evident that immigrants from enemy alien countries were not afforded the right of free speech while the actions of a mob against them could be excused in the right circumstances. Anti-alien demonstrations and meetings were common place in the Winnipeg of 1919.

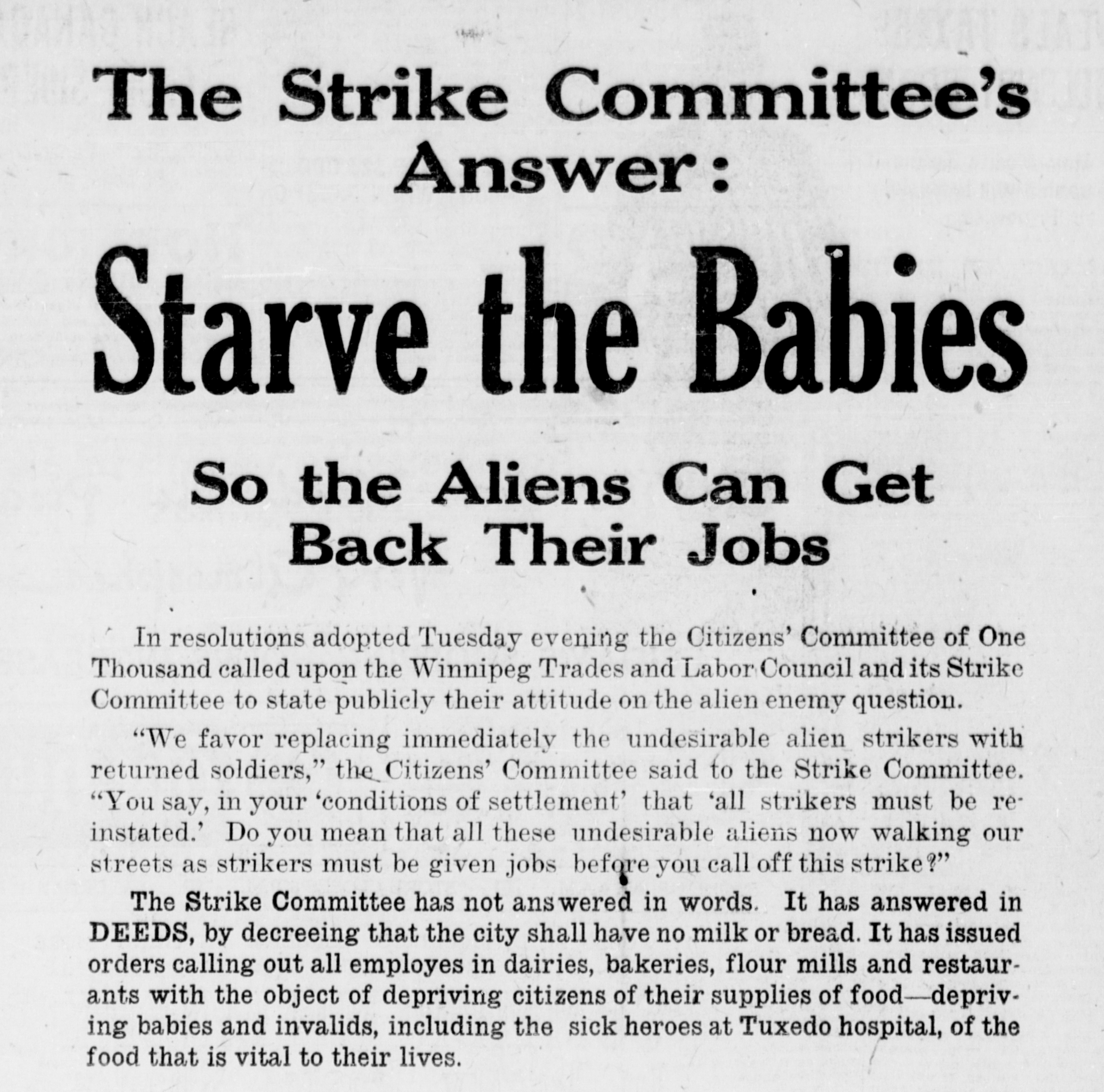

At the start of the strike on May 15, 1919, anti-alien rhetoric became common place in many newspapers, who attempted to use this narrative to bring over strike sympathizers to the opposing side. By blaming the strike on enemy aliens, as opposed to a labour dispute around collective bargaining rights, newspapers such as the Winnipeg Telegram and Winnipeg Citizen hoped to convince Winnipeggers that to support the strike was to support the nations that had fought against Canada during the war. This argument was not always easy to maintain, particularly when many veterans who had fought during the war supported the strike, and most of the strike leaders were British-born, but this alone did not prevent the arguments calling for deportation of aliens during the strike to be made, both by the public and the media.

In the view of the Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand, the strike was a black and white issue: Aliens vs. Soldiers, Aliens vs. Children, Aliens vs. Canadians. An ad published by the committee in the Winnipeg Telegram made this clear: “Choose between the Soldiers who protected you and the Aliens who threaten you!” (Winnipeg Telegram, Jun 5, 1919).

But while the Citizens’ Committee was quick to equate the strike as a foreign-led movement, the Strike Committee was not so quick as to welcome those of Eastern European backgrounds to their ranks. In part, they wanted to sway the veterans to their side, and adopting an open pro-immigrant stance would be counter-intuitive to this aim. Furthermore, immigrants often struggled to find work in Winnipeg, even before the strike. Their best chance at employment was to accept lower wages than other workers, causing resentment among British and Canadian born workers. For this reason, the Strike Committee tried to distance itself from immigrants throughout the strike.

Portrayals of immigrants in the media also showed a clear bias against so-called enemy aliens. When recounting daily strike events, media sources such as the Winnipeg Citizen and the Winnipeg Telegram would often include side notes – ones that made mention of heavy foreign accents or broken English – to ensure readers knew that the strikers and strike sympathizers they were describing were aliens – Germans, Russian Bolsheviks, Eastern Europeans, foreign radicals. In short: enemies.

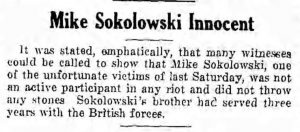

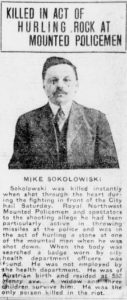

Even in the darkest moments of the strike, the media ensured aliens were identified. The death of Mike Sokolowski on Bloody Saturday was reported in many newspapers, most of which ensured to describe him as an alien and specify that he was in the process of throwing a projectile at police. The Manitoba Free Press reported “Mike Sokolowski, a registered alien shot through heart and instantly killed, presumably while stooping to pick up a missile”, while the Winnipeg Tribune specified Sokolowski was Austrian, “particularly active in throwing missiles at the police and was in the act of throwing a stone at one of the mounted men when he was shot down” (Manitoba Free Press and Winnipeg Tribune, June 23, 1919). The Tribune further implied that Sokolowski was a thief, reporting that he had on his person a badge for the City’s Health Department, of which he was not an employee.

While baseless, the anti-immigration rhetoric was successful in changing legislation on June 6, 1919. Prompted by the events in Winnipeg, the Federal Government amended the Immigration Act, allowing for individuals born outside of Canada to be deported without trial if they were accused of sedition. This would later provide another means through which strike leaders could be arrested. It further restricted immigration to Canada throughout the strike, and after.

Article on Mike Sokolowski. The Enlightener, June 26, 1919. UML.

Deportation Hearings

The newly amended Immigration Act was first put to the test on July 14, when immigration hearings began for four European immigrants who were arrested alongside the British strike leaders on June 17. The arrested men were Samuel Blumenberg, Solomon (Moses) Almazoff, Michael (Max) Charitonoff (sometimes “Charitinoff”), and Oscar Schoppelrei (sometimes “Choppelrei”). A warrant was also issued for Boris Devyatkin, but he had been away at his farm for the last two months, leaving his home in the care of Mike Verenczuk, a Russian born immigrant who fought for Canada in the First World War and who suffered from shell shock. Verenczuk was arrested instead of Devyatkin and spent 17 days in jail before the ‘mistake’ was finally remedied he was released.

The decision to arrest these men and launch immigration hearings was orchestrated by Citizens’ Committee member A.J. Andrews, who also selected the members of the board that would decide the men’s fate. R.M. Noble presided over the hearings as judge and two others, Thomas Gelley and E.T. Boyce, made up the rest of the board. Representing the accused were Marcus Hyman and E.J. McMurray. Noble was not entirely sure how the new amendment to the Immigration Act worked and was unfamiliar with the context of the cases, leaving Andrews and the defense to argue over the facts (Kramer and Mitchel 2010, 218). Noble very rarely sided with the defense. The men were arrested under the criminal code and the Immigration Act was only applied after the fact. This meant anything the men said in the hearings could be used as evidence in future criminal proceedings; they were being forced to produce evidence against themselves. To prevent this, some tried to remain silent, but Andrews simply sent them back to jail and tried again at a later date.

Despite the fact that these men, with the exception of Blumenberg, played only minor roles in the strike, as ‘undesirable’ immigrants, their deportation had symbolic value, particularly Schoppelrei, whose parents were both German. To prove the men sowed sedition, Andrews cited attendance at ‘radical’ gatherings such as at the Walker Theatre meeting in 1918. He called, somewhat ironically, on a Ukrainian immigrant who was a former Mounted Policeman, Harry Daskaluk, to testify against the men. Daskaluk testified that the men spoke seditious words at various gatherings he had infiltrated. He told a similar story at the preliminary hearings of the British-born strike leaders, which was happening concurrently. However, it was discovered that Daskaluk was paid $500 for his testimony and was himself at risk for deportation if he didn’t accept. The defense was able to damage his credibility and Andrews was forced to rely on technicalities.

Almazoff was 29 at the time of his hearing. A Russian Jew from Ukraine, Almazoff had been in Canada for 6 years. He was a student at the University of Manitoba (studying law), an organizer of the Jewish branch of the Social Democratic Party, a member of the Canadian Jewish Congress, and was involved in a number of charitable organizations. He had finished writing his university exams on June 13, four days before being arrested (Bumsted 1994, 76). Andrews had no technicality to use against Almazoff, so he interrogated him on his New York communist connections and brought Daskaluk to the stand to testify that Almazoff had made statements at several gatherings of socialists calling for bloodshed and revolution. The defense discredited this argument and Almazoff gave an emotional speech about how going back to Russia would mean certain death; that he lost a brother when the Tsar’s troops gunned down civilians in 1905 on Bloody Sunday; that he would never want to see such violence repeated in Canada. The board ruled in Almazoff’s favour and he was released. After the hearing, he joined the communist party in New York City and was almost deported again in 1954. He published several books and newspapers in Yiddish and died in 1979 (Kramer and Mitchell 2010, 408n32).

Blumenberg was deported based on a technicality as well. He was a Romanian Jew that had lived in Minneapolis before coming to Canada. He said at the border that he was an American citizen, not realizing that technically he was not. Despite all the evidence of sedition Andrews produced, it was this minor technicality that led to his deportation.

For more on Blumenberg, see Who: Strike Leaders

Charitonoff, like Almazoff, was a Russian Jew. He was born in Nicolaieff on the Black Sea and had spent time in New York and Philadelphia before coming to Canada. At the time of his hearing, Charitonoff was 27, had been living in Canada for almost five and half years, and worked at the CPR freight shops. In 1917, he edited the Russian language newspaper Rabochi Narod (Working People) for the Ukrainian Social Democratic Party, until it was banned the following year. He was on the stage at the Walker Theatre meeting, which Andrews tried to use against him, but it once against came down to a technicality. Charitonoff had tried to enter the country once before; he had done nothing illegal and hadn’t lied about anything, but was rejected because he did not have enough money and the proper ticket. This was enough for the board to vote in favour of deportation. However, Charitonoff appealed and the decision was reversed. Charitonoff rarely talked about the strike afterwards and lived a quiet life. He took a sales manager job at his brother-in-law’s furniture store in 1920 and worked there until 1960 (Kramer and Mitchell 2010, 409n48).

Schoppelrei, 22 at the time of his hearing, was born in Superior, Wisconsin to German parents. He was an unemployed musician whose wife had died of influenza. He came to Canada in 1918 to enlist in the Canadian forces to fight in the First World War. He lied and said he was born in Québec, which was technically illegal, but the Canadian military encouraged it as they desperately needed more soldiers. During the strike, he helped to organize pro-strike returned soldiers. His lie at the border was enough for the board to rule: he was deported back to the United States. In 1920, Schoppelrei remarried in Hennepin, Minnesota and had three children. They divorced in 1927 in Milwaukee, Wisconsin (Kramer and Mitchel 2010, 409n39).

Since their June 17 arrests the four men had spent two months in jail without bail. After Charitonoff’s hearing, Marcus Hyman summed up his thoughts on the hearings by saying, “I had a sleepless night last night. I lay thinking: Am I insane? Is this a nightmare? Is this a delusion I am laboring under that I have to meet trifling, ridiculous charges of this kind under the British Empire and the British Flag?” (Kramer and Mitchell 2010, 286).

People of Colour

Perhaps the largest gap in General Strike narratives is that of the experiences of people of colour. Prejudice and the concept of the ‘other’ are central themes in many strike narratives, but the focus has generally been on those from Central and Eastern Europe. People of colour are rarely mentioned. In most cases, people of colour were left out of unions, either explicitly, by being refused membership outright, or implicitly, by being left out of the decision making process and passed over for leadership roles. This exclusion also meant that people of colour were more likely to work as unskilled labourers, even if they possessed specific skill sets.

Indigenous peoples were the first in Canada to resist Western capitalism and colonialism. They worked in a variety of industries and engaged in strike action when necessary. As early as 1829, Cree boatmen in Oxford House, who were paid 10 pelts per season, refused to go back to work for the Hudson’s Bay Company until they were paid 40 pelts per season, as those in York Factory were receiving. Colonial policy confined many Indigenous peoples to reserves, where their labour fell under the yoke of the Department of Indian Affairs. As well, children in the genocidal residential school system were often put to work by force. However, some Indigenous peoples lived in Winnipeg, often finding work as labourers or domestic help. Rooster Town was the name used by settlers to describe a Métis community on the southern outskirts of Fort Rouge, in what is now the Grant Park area. It developed alongside Winnipeg as Métis began to take up residence in Fort Rouge around 1900, but over time, its residents were pushed farther south as Winnipeg expanded. The residents of Rooster Town were nothing if not adaptable and found ways to support their families. The exact effect the strike had on the residents of Rooster Town has not been thoroughly explored, but given that much of their livelihood relied on seasonal and temporary work, it is likely that the six week strike would have disrupted this. Thousands of non-unionized workers were involved in the strike, and it is entirely possible that some of them were Métis residents of Rooster Town. It is also possible that they took advantage of vacant positions to help support their families.

This was true for other groups as well, such as Winnipeg’s Chinese population. Winnipeg’s Chinatown has existed since the early 1900s, including several Chinese owned businesses that would have been affected by the strike. Some worked at or owned laundromats, restaurants, and other small businesses that were targeted by returned soldiers in the January riots.

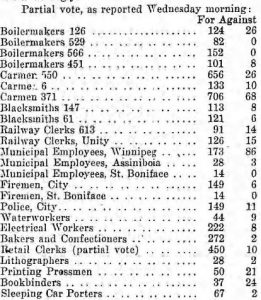

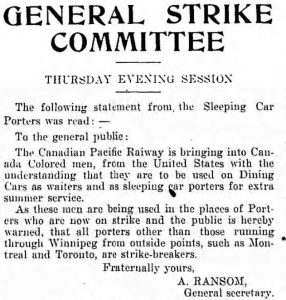

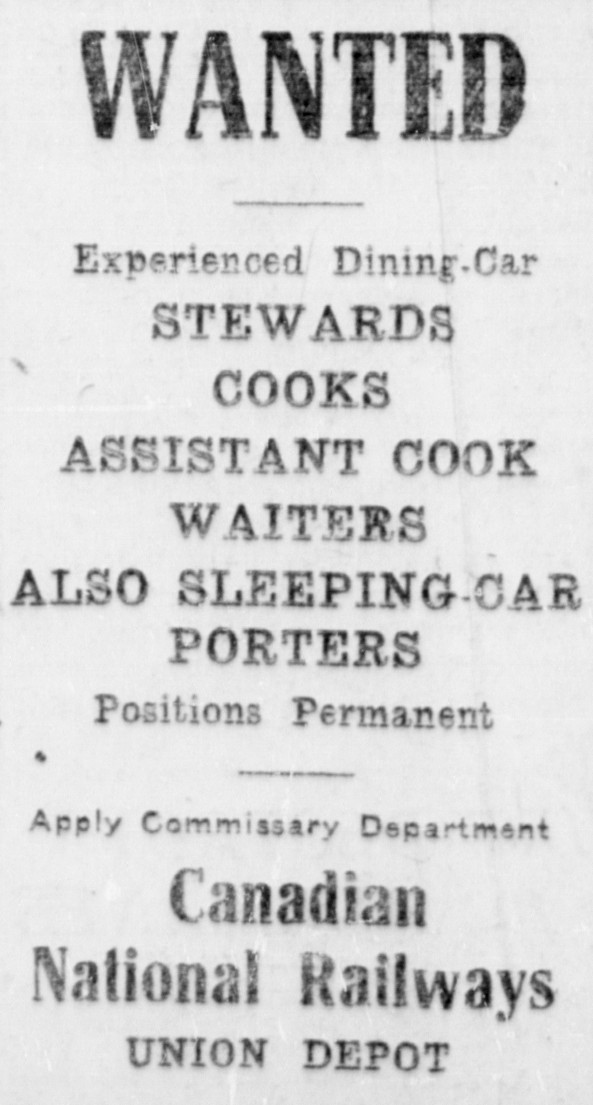

Many black Canadians worked on the railroads as sleeping car porters who assisted and attended to passengers. The porters unionized under the leadership of John A. Robinson, who led them during the General Strike. Born in St. Kitts, Robinson was well established in Winnipeg by 1919. He lived in the North End at Main Street and Selkirk Avenue, surrounded by several of Winnipeg’s black-owned businesses (Mathieu 2010, 124). In 1917, Robinson and a group of black porters attempted to join the Canadian Brotherhood of Railway Employees, but were turned down. The Brotherhood was for whites only. Not to be deterred, Robinson organized his own union, the Order of Sleeping Car Porters (OSCP). Despite receiving little in the way of solidarity from white workers, Robinson contemplated joining the strike when it began. Joining the strikers could lead to white resentment and targeted violence, but so could not joining the strikers. A vote was taken and the OSCP voted overwhelmingly to join the strikers. Ninety-nine porters walked off the job and the OSCP even gave a donation of $50 to the Strike Committee. The Western Labor News lauded this action and acknowledged this partnership, defending black workers when replacement workers were shipped in from the United States (Mathieu 2010, 127). OSCP members did not come out of the strike unscathed, however. Frequent ads ran in Winnipeg’s daily papers offering permanent positions to those who replaced the striking porters. After the strike ended, only 29 of 99 porters were re-employed (Winnipeg Tribune, September 8, 1919). The OSCP eventually merged with the Brotherhood.

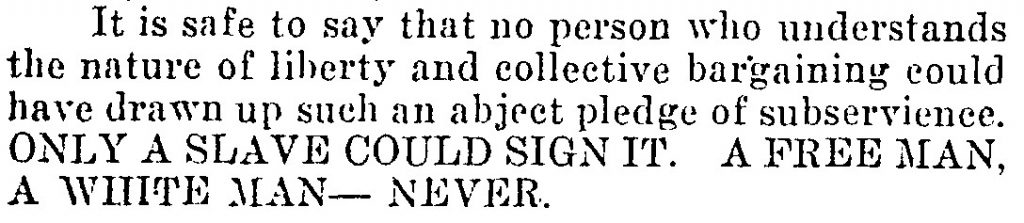

Race was also used symbolically during the strike. Racialized language was often used that associated ‘colour’ with bondage and inferiority. Strikers, for example, frequently invoked the word “slave” to describe their plight. The most explicitly racialized example was the language used in references to the Slave Pact that all returning City employees had to sign and which limited their powers to unionize. The Western Labor News said of the pact, in all capital letters, “ONLY A SLAVE COULD SIGN IT. A FREE MAN, A WHITE MAN – NEVER” (Western Labor News, June 2, 1919). The implications were clear; freedom and self-determination were considered the innate inheritance of white workers, not workers of colour.