May 2, 1918

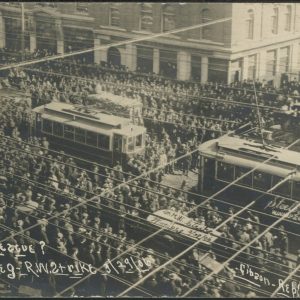

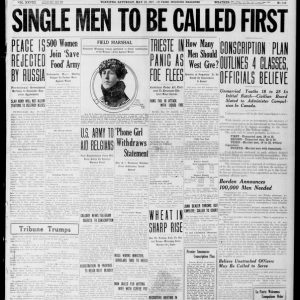

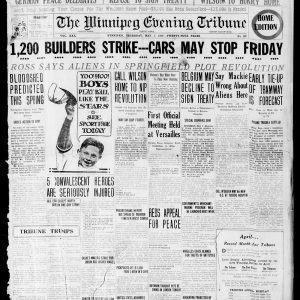

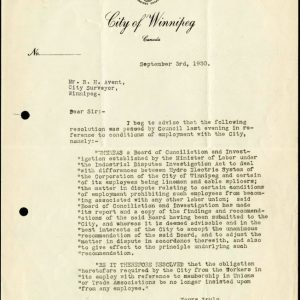

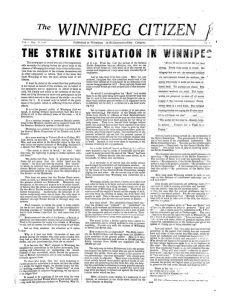

City of Winnipeg Electrical employees go out on strike over disagreements relating to a pay increase. The City threatens to dismiss the workers and sympathy strikes begin.

May 9, 1918

Council organizes a Special Committee on Strike Settlement to negotiate with the strikers.

May 13, 1918

Having reached a tentative deal with the strikers, the Special Committee presents its report to Council.

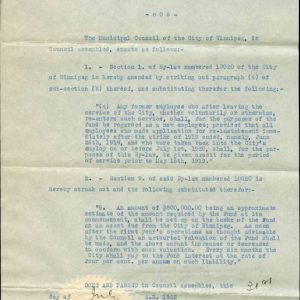

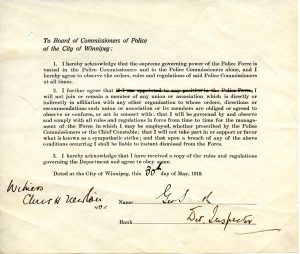

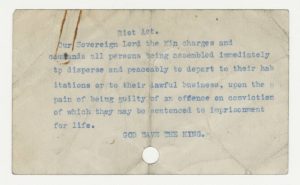

Alderman F.O. Fowler convinces a slim majority of Council to amend the agreement to forbid City employees from unionizing or striking in the future.

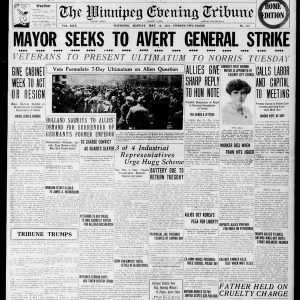

May 14, 1918

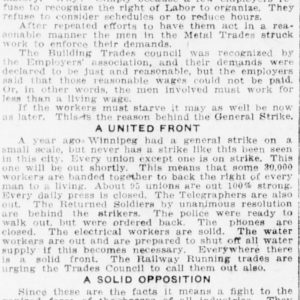

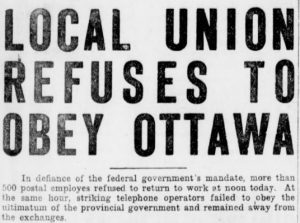

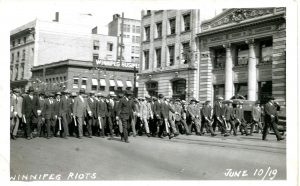

In response to the new law, city firefighters walk off the job and the ongoing strike intensifies. A general strike is threatened.

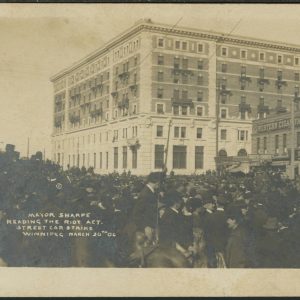

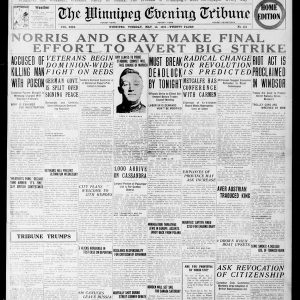

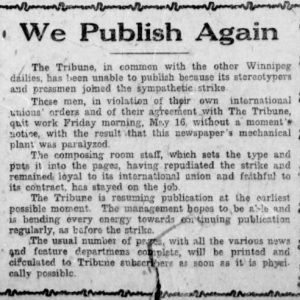

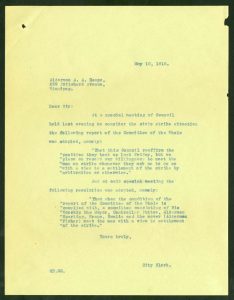

May 16, 1918

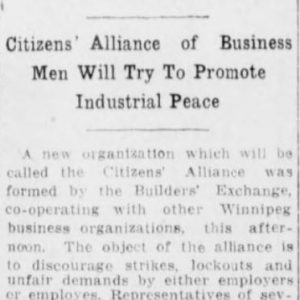

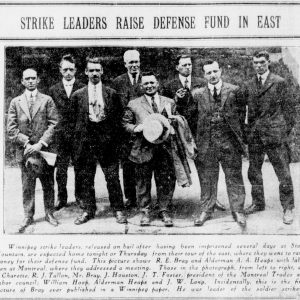

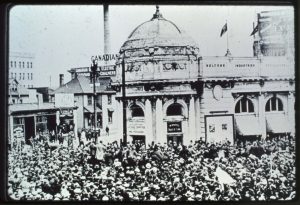

A meeting of business owners and employers meet to discuss the strike and organize the Citizens’ Committee of One Hundred to help negotiate between the City and the strikers.

May 17, 1918

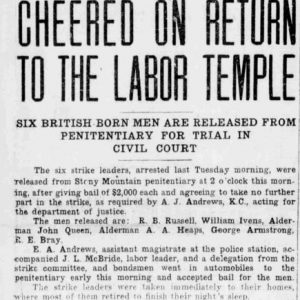

The Citizens’ Committee of One Hundred is formed.

May 24, 1918

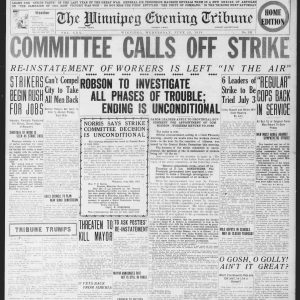

A settlement is reached, abolishing the ban on strike action. In exchange, firefighters agree that they will give sixty days’ notice prior to any strike action, that they will only strike over grievances deemed serious, and that officers will not be eligible to be part of the union.